A Traitor to the Treasonous: John E. Cook

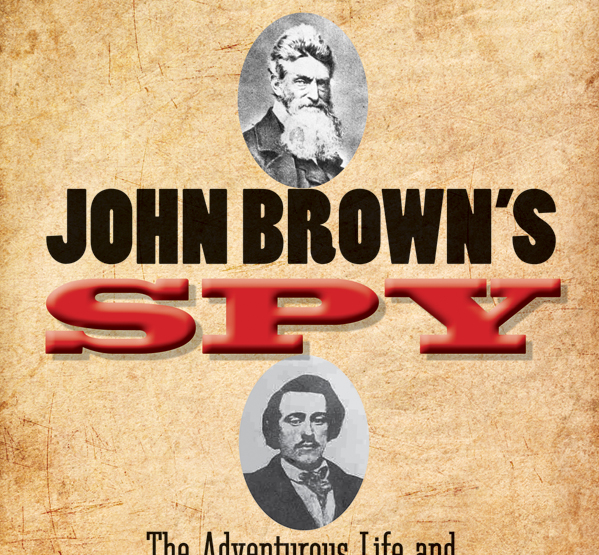

“The Battle Hymn of the Republic” sings “As he died to make men holy/Let us die to make men free,” about American hero John Brown. Brown’s Raid at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, although unsuccessful on many accounts, has provided fodder for conversations about freedom for decades. John Brown failed to capture the national armory, but he did secure himself a place in American folklore as martyrs and champions for the abolitionist movement. But little has ever been told of the 21 men who fought with John Brown, those inspired and convinced and, in most cases, ended by the historic raid. Steven Lubet, in his new book John Brown’s Spy: The Adventurous Life and Tragic Confession of John E. Cook, reveals the tale of John Brown’s most trusted confidante and partner in crime.

Lubet takes great care in describing both the type of person John E. Cook was and the circumstances under which he was entrusted with such a large burden of information. John Brown had some financial backers in the North, but he was unable to rally most abolitionists groups to join him, as most found his ideas and actions to be too radical. Thus, John Brown needed anyone willing to help him, enlisting the help of his own sons just to reach an army of twenty-one men. Brown was desperate, which explains his choice of Cook, who was a notorious loud-mouth, constant poet, and prolific ladies’ man. Cook was young and wrapped up in the romanticism of the movement. He quickly became Brown’s number one man, even heading to Harper’s Ferry early to scout out the armory and its key players. Lubet maintains that Cook was indispensable throughout the preparation, writing:

Lubet takes great care in describing both the type of person John E. Cook was and the circumstances under which he was entrusted with such a large burden of information. John Brown had some financial backers in the North, but he was unable to rally most abolitionists groups to join him, as most found his ideas and actions to be too radical. Thus, John Brown needed anyone willing to help him, enlisting the help of his own sons just to reach an army of twenty-one men. Brown was desperate, which explains his choice of Cook, who was a notorious loud-mouth, constant poet, and prolific ladies’ man. Cook was young and wrapped up in the romanticism of the movement. He quickly became Brown’s number one man, even heading to Harper’s Ferry early to scout out the armory and its key players. Lubet maintains that Cook was indispensable throughout the preparation, writing:

Only weeks before the insurrection, there was a near mutiny among the men that almost caused the collapse of the entire enterprise. At that critical moment, however, Cook played a decisive role in quelling the rebellion. He strongly endorsed Brown’s leadership, and he convinced the most apprehensive raiders to remain in the fold. Without Cook’s support, Brown might have seen his twenty-one-man army dwindle away, perhaps requiring him to delay or even cancel the uprising.

But Cook is not revered as an accessory to an event that tightened the tensions between the American North and South. Instead, he is remembered as a traitor to Brown’s army, eventually confessing his secrets to his captors, unable to keep his mouth shut. Steven Lubet brilliantly tells the tale of this excitable and flawed performer of American history.