Jackie Kennedy: Warhol’s and Richter’s Painted Spy

John J. Curley—

With his assassination fifty years ago, President Kennedy became the Cold War’s most famous victim. Befitting the conflict’s secret ruses and double agents, the assassination was, from the start, rife with proliferating conspiracy theories. It is in this context of interpretative fancy that we must consider two paintings featuring Jacqueline Kennedy created in the aftermath of November 22, 1963: Andy Warhol’s Thirty-Five Jackies (Multiplied Jackies) and Gerhard Richter’s President Johnson Consoles Mrs. Kennedy. While ostensibly legible, both of these portraits are not what they seem; like spies, Warhol’s and Richter’s painted Jackies also misdirect and dissemble. If the Cold War, as Marshall McLuhan suggested in 1964, was an “electric battle of information and of images,” then these two canvases demonstrate a hidden struggle over interpretation.

With his assassination fifty years ago, President Kennedy became the Cold War’s most famous victim. Befitting the conflict’s secret ruses and double agents, the assassination was, from the start, rife with proliferating conspiracy theories. It is in this context of interpretative fancy that we must consider two paintings featuring Jacqueline Kennedy created in the aftermath of November 22, 1963: Andy Warhol’s Thirty-Five Jackies (Multiplied Jackies) and Gerhard Richter’s President Johnson Consoles Mrs. Kennedy. While ostensibly legible, both of these portraits are not what they seem; like spies, Warhol’s and Richter’s painted Jackies also misdirect and dissemble. If the Cold War, as Marshall McLuhan suggested in 1964, was an “electric battle of information and of images,” then these two canvases demonstrate a hidden struggle over interpretation.

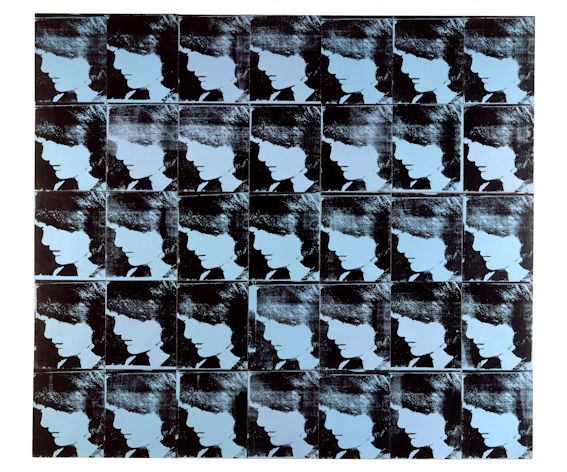

Warhol’s Thirty-Five Jackies is made up of thirty-five small canvases arrayed in a grid, each with the same silkscreened visage. The artist selected a famous source image associated with the Kennedy assassination: Jackie in a blood-stained dress, looking on as Lyndon Johnson is sworn-in aboard Air Force One. Through tight-cropping and repetition, Warhol drains the emotional power out of Cecil Stoughton’s original image, and the widow becomes part of a larger decorative scheme. Additionally, Warhol’s technique – a roughly rendered silkscreen – barely registers the particulars of Jackie’s countenance. Viewers recognize her only because of the iconic and highly visible nature of the source photograph. The painting, in many ways, fails as a likeness of the former First Lady.

Andy Warhol, Thirty-Five Jackies (Multiplied Jackies), 1964. Silkscreen ink and acrylic on canvas, 100 2/3 x 113 in. (255.7 x 286.8 cm). MMK Museum für Moderne Kunst Frankfurt am Main, former collection of Karl Ströher, Darmstadt. © 2012 The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

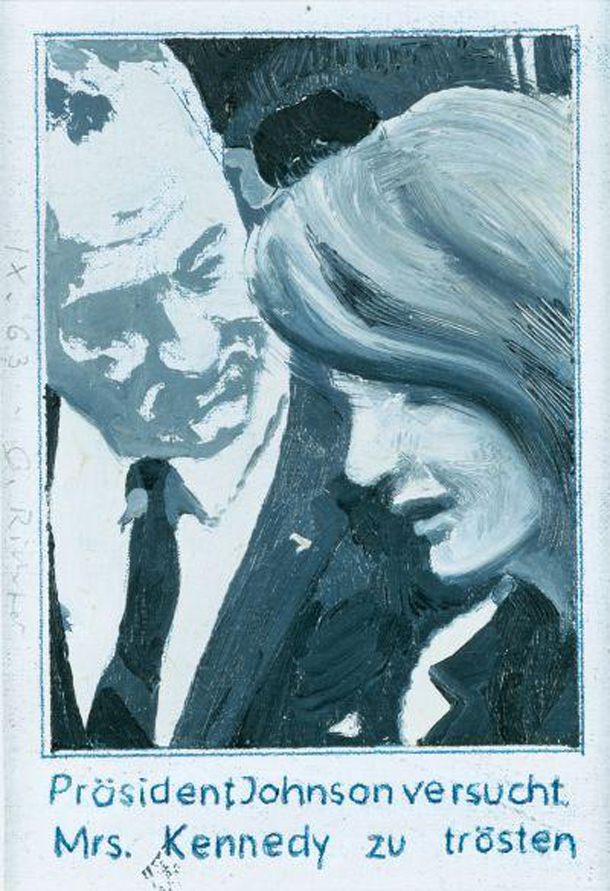

In my new book, A Conspiracy of Images, I discuss Richter’s Woman with Umbrella, which also features Jacqueline Kennedy. However, here I want to focus on a second Jackie painting about which I have recently uncovered new material: President Johnson Consoles Mrs. Kennedy. In this small and understated work, Richter also chooses to paint a Stoughton photograph, but one taken just after the moment of Warhol’s source image. Crudely realized by hand, Richter’s picture also renders the slain president’s widow (and LBJ) as an ambiguous collection of painted marks. For instance, the painterly flourish of Jackie’s hair obscures half of her face, and, at the bottom, the bodies of the new President and former First Lady are confused in a mass of black paint. But just in case a German viewer could not recognize the depicted scene, Richter provides a painted caption (which is also the work’s title) identifying the protagonists and action.

Gerhard Richter, President Johnson Consoles Mrs. Kennedy, 1963. Oil on canvas mounted on card, 5 x 3 1/2 in. (12.7 x 8.9 cm). © Gerhard Richter 2013, courtesy Atelier Gerhard Richter, Cologne.

In these two works, Warhol and Richter depict and obscure Jacqueline Kennedy. While at first glance each painting seems clear, a sustained viewing renders the ambiguity of their common subject. It is only when these respective works are considered as paintings, as pictures arrested from the torrential flow of the mass media and subsequently transformed into works of art, that their strangeness as images emerges. Considering the mystery surrounding JFK’s murder, which immediately inspired tales both plausible and far-fetched, Warhol’s and Richter’s paintings of Jackie thus thematize their own conspiracies of looking. It is strange still today how the wide distribution and visibility of their source images, trick us into overlooking their unintelligibility.

When we consider the original press context of Stoughton’s historic images, the conspiracy may go deeper. Likely transmitted by phone lines and then hurriedly printed on cheap paper for popular magazines and newspapers, the images were already unclear in their “original” published state. I recently discovered the precise (and, to my knowledge, previously untraced) source for Richter’s painting, a special issue of Berliner Illustrierte rushed to the stands after the events of late November 1963. (While this photo was widely published, the matching captions secure this example as Richter’s source.) The presence of Warhol’s image choice in this same page spread highlights the global reach of photographs at this moment. After seeing the image degradation in this media source and others in Life or the New York Times, Warhol’s and Richter’s respective painted blurs are not necessarily additive; instead we could say that they are approximating, through different techniques of painting, the ambiguous quality of the original published images. By re-transmitting an already published (or already-transmitted) photo, these works demonstrate how the very act of media dissemination degrades the image and allows it to work against the certainties usually associated with press photography.

Page spread from Berliner Illustrirte, Special Issue 1963 (December), featuring United States Army Signal Corps photograph (top) and two photographs by Cecil W. Stoughton (bottom).

It is important to note that Stoughton’s original photographs were not just sensational images, but also ideologically important for Cold War America; they showed the world an orderly and respectful transfer of presidential power. (LBJ, according to Robert Caro, was adamant that Jackie be present at the swearing-in for just this photographic proof of regime continuity.) During these particularly tense years of the Cold War – in the aftermath of the Bay of Pigs and the Cuban Missile Crisis – any signs of domestic chaos or perceived uncertainty about who was in charge could prove disastrous to U.S. creditability. Warhol’s and Richter’s sources were ideological photos hiding under the guise of topical and spectacular news.

Both artists knew all about making ideological images that appeared otherwise. In the 1950s, Warhol was a commercial (i.e. capitalist) artist in New York, and Richter painted official murals in socialist East Germany, before he escaped to West Germany in 1961. Considering their antithetical backgrounds, their mutual turn toward fashioning blurry versions of found media photographs in 1962 is significant. Both artists recognized that mass media images constituted a vital front in the Cold War and used their work, as with their paintings of Jackie, to intervene, however stealthily, into the conflict’s interrelated battles of images, ideology, and art. While Warhol and Richter are, without a doubt, two of the most important individual artists of their generation, isn’t it time to bring their paintings in from the cold?

John J. Curley is assistant professor of art history at Wake Forest University.