Whitney Biennial Hoopla—David Ebony Interviews the Curators: Stuart Comer, Anthony Elms and Michelle Grabner

David Ebony—

One of the most prestigious exhibitions of contemporary art the U.S. has to offer, the Whitney Biennial claims to be a bellwether for new trends, important young artists and all sorts of innovative ideas. For that reason, the exhibition inevitably sparks heated controversy, and the 2014 installment is no exception. This time, museum director Adam D. Weinberg and Donna De Salvo, chief curator and deputy director of programs, invited three outside curators to organize the exhibition, which opened in New York on March 7, and runs through May 25. Selected for the job were Stuart Comer, formerly a film curator at Tate Modern and now chief curator of media and performance art at the Museum of Modern Art; Anthony Elms, associate curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, in Philadelphia; and Michelle Grabner, an artist and professor of painting and drawing at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago as well as a teacher at Yale. While curatorial teams and pairs are common in organizing a large-scale museum show like this, the Whitney’s assignment is unusual in that each curator was given a separate floor in which to convey his or her view of the state-of-art today.

Whitney Biennial 2014 curators (left to right): Anthony Elms, Stuart Comer, Michelle Grabner; Photo Filip Wolak; courtesy Whitney Museum of American Art.

The curators chose a total of 103 artists working in a wide variety of mediums. Expectations ran high for the show, particularly as it happened to appear within the same year as a number of extraordinarily successful and well-received international surveys of contemporary art—including the Venice Biennale, the Lyon Biennale and the Carnegie International, among those I’ve seen. For that reason, the Whitney show has met with unusually intense critical scrutiny, and reviews have been mixed. The show’s novel curatorial setup was the primary focus of some critics, and the fact that approximately forty percent of the artists are over 50 or deceased called into question the presumed mandate of an exhibition intended, for better or worse, to herald the latest trends.

In the wake of all the hoopla surrounding the Biennial’s opening and the fallout from initial critical reactions, I spoke with all three curators to get a sense of their own personal and professional responses to the exhibition now that it is up and running. In the interviews below, complied from in-person discussions, telephone and email exchanges, the curators describe in depth their aims for the show and what they have accomplished. They also express their feelings about how their efforts have so far been perceived by the public and press.

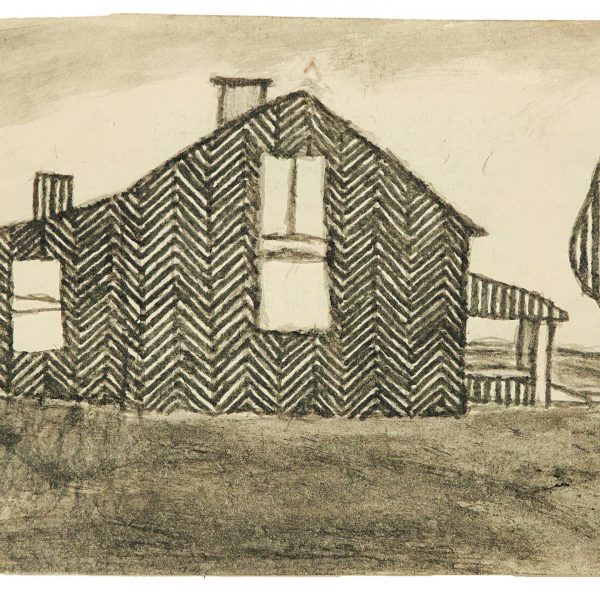

Installation view Whitney Biennial 2014 ( March 7 – May 25, 2014), fourth floor.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

Left to right: Jacqueline Humphries, Sterling Ruby, Dona Nelson, Pam Lins and Amy Sillman

David Ebony: Michelle, in your essay for the Biennial catalogue, you state that in your section of the Biennial, “Contours can be drawn around three overlapping priorities: abstract painting by women, materiality and affect theory; and art as strategy.” Could you elaborate on those themes, and describe how you think they have been realized in the exhibition?

Michelle Grabner: I settled on these three thematics because of their intensity within contemporary art. I would say that materialism and affect theory are the most politically compelling in visual culture today. The fact that we “feel” our way through the world, and that we are secure in our intuitive interpretation of it, is a very different sort of navigation than employing obvious critical faculties.

I set up a dichotomy between the two main galleries on the fourth floor. The south gallery hosts work that invites critique and overtly engages with critical theory. It features works by Sarah Charlesworth, Ken Lum, Gretchen Bender and David Diao, all of whom made their reputations in the 1980s. But it also contains pieces by Philip Vanderhyden, Shana Lutker and Karl Haendel, younger artists who employ appropriation, irony and in-depth critical examinations of cultural signs. In this gallery, authorship, the art market and entertainment media are subjected to interrogation.

Installation view of (in center of frame) 84 Bottoms Up, 2013 and (in background) Curtains Laced with Diamonds Dear for You, 2014 by Joel Otterson. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- May 25, 2014. Collection of the artist; courtesy Maloney Fine Art, Los Angeles. Photograph by Bill Orcutt.

By contrast, materiality rules the day in the central gallery with large-scale abstract painting, fiber pieces, ceramics and woodworking. Joel Otterson’s massive beaded curtain suspends rusty, old and antiquated hand tools as a kind of lament. Yet the tactile beauty in his lace tent, quilted blanket and glassware chandeliers can be seen as a purely material celebration of life. Sheila Hicks, Alma Allen, and John Mason are also extraordinary artists working with the language of traditional craft. It was important for me to juxtapose their works with Sterling Ruby’s ceramic “basins” and a powerful selection of ambitious abstract paintings by women—including Amy Sillman, Suzanne McClelland and Louise Fishman—to illicit a profoundly visceral viewing experience.

Installation view of Pillar of Inquiry/Supple Column, 2013-14 by Sheila Hicks and Notley, 2013 by Molly Zuckerman-Hartung. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- May 25 2014. Collection of the Artist; courtesy of Sikkema Jenkins & Co., N.Y.; Collection of the artist; courtesy of Corbett vs Dempsey, Chicago. Photograph by Bill Orcutt

Ebony: Anthony, your part of the exhibition seems to have a deliberate airiness to the installation that is distinct from the other two floors. Were issues of the public space of the museum and the viewer’s circulation through the exhibition a primary concern? Also, in your Biennial catalogue essay, you write the striking line, “It is the device of aphorism that allows this curator to navigate.” Could you talk more about this idea and your use of the space?

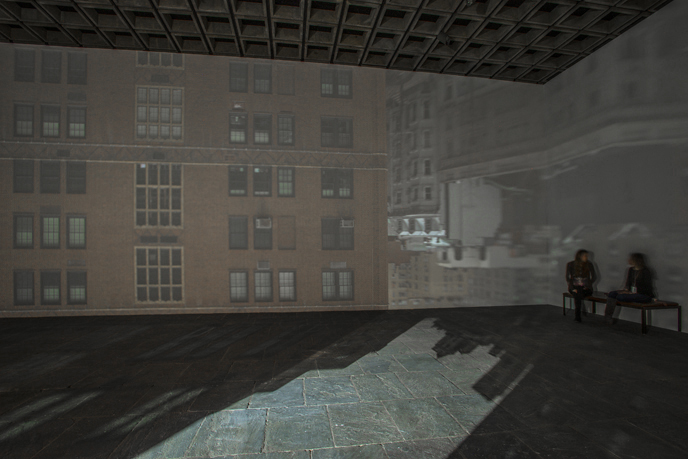

Anthony Elms: I knew the exhibition had to have a lot of space because of the great amount of compression and density in so many of the individual works on view—Reinke and Mott, Joseph Grigely, Michel Auder, Public Collectors, Charline von Heyl, Susan Howe, etc. The first piece to fall into place for me was Zoe Leonard’s “camera obscura” installation on the fourth floor. This is a piece that requires a considerable amount of space and time to do what it does. With that installation set, I used it as a model for the pacing and the spacing of everything on the second floor. I don’t want to imply that Leonard’s is the most important work in my selection, but simply that I didn’t want the other pieces to compete with it.

Installation view 945 Madison Avenue, 2014, lens and darkened room by Zoe Leonard.

Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- May 25 2014.

Collection of the artist; courtesy Murray Guy, N.Y., and Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

Photograph by Bill Orcutt

As for aphorisms, well, I am an aphoristic thinker. Love them. The essay I wrote is sprinkled with aphorisms here and there. Some make sense, others are elusive perhaps. I didn’t want to assign specific aphorisms to individual works. I think of an aphorism as a kind of energy source. Certainly some of this energy can be found in sections of the Reinke and Mott video, portions of My Barbarian’s performance and the Allan Sekula notebooks. Robert Ashley’s compositions can be rife with incisive aphoristic delight—if you’re attuned to it.

Installation view Whitney Biennial 2014 ( March 7 – May 25, 2014), 2nd floor.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

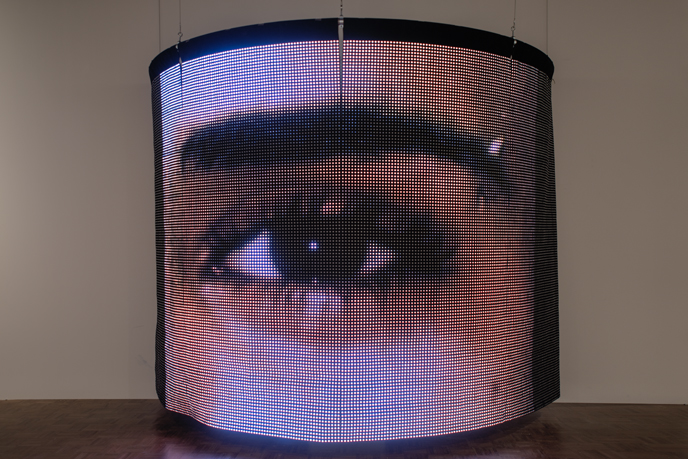

Ebony: “The exhibition seeks to reflect [a] tendency towards shape-shifting, whether through complex relationships between linguistic and visual forms,” is a line that stood out to me in Stuart’s catalogue essay. Could you please give a few examples of this “shape shifting” process, using just two specific works that appear in your exhibition?

Stuart Comer: What I’m trying to highlight in the exhibition is the linguistic sign and the way it conjoins language and image. In recent years there’s been a dramatic evolution in the way the linguistic sign operates, a radical shape-shifting process that is largely due to the internet. I chose some fundamental examples to start with, such as the works by Etel Adnan, who is 89. In Lebanon, she’s heralded as a major poet. But she’s also a visual artist and her paintings have a strong connection to her writing. Her work is a very clear demonstration of the interdisciplinary approach I was looking for. Jacolby Satterwhite’s 3-D animation videos are another good example. The images are derived from his mother’s drawings and writing. He pushes this binary of image and text toward something magical.

Installation view Aviarium, 2014 by Terry Adkins. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- May 25 2014. Photograph by Bill Orcutt

Ebony: Now that the main part of the show has been realized, except, of course, for all the performances and other live programs, how does the exhibition differ from your expectations in anticipation of the show? Is there anything you would have done differently?

Grabner: Not a thing. I’m very proud to have had the opportunity to highlight 53 dedicated artists, many whom I cherish as great influences on my own studio practice over the years. The only thing that has taken me by surprise is the critical response to the show. For many critics, it seems as if the curatorial conceit of this Biennial is more compelling to discuss than the actual artworks. Clearly, it’s impossible to take an objective measure of “new contemporary American art” from a curatorial or an exhibition stand-point, so why not focus on the many artworks in the exhibition instead? There is so much to be learned from the artists and the works in the show.

Elms: The exhibition and my expectations of it are still evolving as the performances and screening programs commence. But even in seeing the objects together everything changes. Every time I return to the exhibition it changes. I’m still noticing new details to the assembled pieces. I wouldn’t change anything about the show. If I did it again, I would naturally do it differently; but this is the exhibition it was meant to be. The artists have actually exceeded my expectations.

Comer: The thing that none of us could foresee was how the three floors would work together—or not. I’m happy with the way our ideas and the messages we wanted to convey come across in the show. With multiple viewings, it’s interesting to see how intended meanings fluctuate—some predominate and others get a bit obscure. And it’s also interesting to see how well the installation interacts with the building as a whole.

I think all three of us responded in some way to the fact that this is the last Whitney Biennial in the Marcel Breuer building. We’re all fond of the building. We didn’t want to turn the place into a kind of mausoleum, certainly, but there is an aspect of the exhibition that has to do with a sense of retrospect as well as looking ahead. Morgan Fisher’s large drywall construction [Ro(Ro(Room)om)om, 2014], for instance, combines a part of Breuer’s Whitney design with elements of Renzo Piano’s for the new Whitney building opening in the Meatpacking District next year.

Installation view The Gregory Battcock Archive, 2009-14 by Joseph Grigley and Rebecca Morris

Installation view Whitney Biennial 2014 ( March 7 – May 25, 2014), 2nd floor.

Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Photograph by Sheldan C. Collins

Ebony: What do you hope viewers will notice about your part of the exhibition that, so far, critics and commentators have missed?

Grabner: My hope is that viewers will get a sense of the value systems evinced in the exhibition. As the first actively engaged studio artist to curate the Whitney Biennial, I think that viewers will see on the fourth floor the prominence of autonomous “things” and an emphasis on art’s materiality. I also hope that viewers will not shy away from considering my loosely “contoured thematics” and identify the overlaps among them. Hopefully, they can build their own understanding of the forces at work in contemporary art.

Comer: So far, with the mainstream critics, it seems clear to me that we have a generation that have interesting things to say about painting and sculpture but are not adept at discussing time-based media. There’s a digital divide—a disconnect between discussions of pre-digital works and art of the digital age. Hardly anyone seems to be addressing this issue. The artist discourse has changed, and some critics’ responses seem out of date. I hope they’ll look a little more closely next time and think about the qualities in the works. Of course, a museum show should be a strongly visual experience. But there’s also a huge potential for delivering an anecdotal experience as well. There are a lot of narratives that span the individual works in the Biennial, and the stories they tell are very interesting.

Installation view Untitled, 2014 by Gary Indiana. Whitney Biennial 2014, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 7- May 25 2014. Collection of the artist. Photograph by Bill Orcutt

Elms: I’ve not been reading the reviews, except for Holland Cotter’s [New York Times] and Peter Schjeldahl’s [The New Yorker]. What has been missed in general? I don’t know. I will simply say that no matter the circumstances, people should pause to notice the details. Many of the pieces I chose are about details that both make a whole and also complicate any overall structure that might be noted. I hope they take the time to look, listen, and perhaps grow astonished at what some remarkable people have accomplished. It’s easy to forget that exhibitions are about the art on view. Attend to it. There is a visual sense at play, and it is conducive to those who choose to make time rather than simply mark time.

David Ebony is currently a Contributing Editor of Art in America and its former Managing Editor, part of an association with the magazine that spans over 21 years. He has written for A.i.A. more than 450 signed articles, including features, reviews, profiles and news stories. He is also a senior editor-at-large for SNAP Editions, based in New York. He is the author of “David Ebony’s Top 10,” a long-running contemporary art column for Artnet.com, which is accessible on the Artnet web site. He was a Contributing Editor and writer for Lacanian Ink, (from 1998-2012), a journal of art and psychoanalysis. He served for two years (2002-2003) on the Board of Trustees of AICA, the Association internationale des critiques d’art, of which he is a long-standing member. He lives and works in New York City and Clermont, New York. Among his books are Anselm Reyle: Mystic Silver (2012); Carlo Maria Mariani in the 21st Century (2011), Dale Chihuly; Garden Installations (2011); Emily Mason (2006); Botero: Abu Ghraib (2006); Craigie Horsfield: Relation (2005); and Graham Sutherland: A Retrospective (1998).