Multimedia Masquerade—Masks and Disguise in Contemporary Art: Interview with Pamela McClusky by David Ebony

David Ebony—

As Performa 15, the performance art biennial, gets underway this week in New York, on the West Coast, Los Angeles’s Fowler Museum at UCLA hosts “Disguise: Masks and Global African Art,” an extraordinary look at the use of masks in contemporary performance art, sculpture, photography, installation and video. Highlighted in the show are works by 24 mostly young artists, from Africa or of African descent, who explore in their art the psychological and metaphysical implications of disguise, identity transformation, and metamorphosis. Appearing at the Fowler through March 13, 2016, the exhibition was organized by Pamela McClusky, Seattle Art Museum’s curator of African and Oceanic art, in collaboration with consultant curator Erika Dalya Massaquoi. The show debuted in Seattle this past summer, and subsequent to its Los Angeles run, travels to the Brooklyn Museum of Art, April 29-September 18, 2016.

The exhibition explores the notion of using masks, props, masquerades and illusions to get to truthfulness—or more real versions of the “real.” Many of the works incorporate masks from the Seattle Art Museum’s acclaimed collection of African art. I find the show especially appealing since it includes several young artists whose works have captivated me in the recent past. Among these, Saya Woolfalk’s haunting figurative images in collage, video and installation pieces made for an unforgettable studio visit, and a remarkable gallery show of installations and videos at Leslie Tonkonow in Chelsea last year; Jacolby Satterwhite’s video works were among the highlights of last year’s Whitney Biennial; and Ebony G. Patterson’s glittery textile constructions, featuring poignant themes related to her native Jamaica, were standouts in 2014’s Prospect 3 in New Orleans. Also memorable was a recent studio visit with Toyin Odutola, a Nigerian-born New York artist with an innovative approach to the figure, whose work is included in the show.

“Disguise” is intended to be an evolving, performative exhibition, immersive and interactive. McClusky and Massaquoi commissioned ten artists to create new pieces specifically for the show and directly corresponding to its theme. Working in a wide range of mediums, the commissioned artists, including Woolfalk and Satterwhite, Sam Vernon, Emeka Ogboh, Brendan Fernandes, Nandipha Mntambo, Walter Oltmann, Wura-Natasha Ogunji, Zina Saro-Wiwa, and Jakob Dwight, may not be exactly household names in the U.S. at the moment, but this exhibiti

on will likely bring these emerging talents new and appreciative audiences.

Since a trip to Los Angeles does not figure into my immediate travel plans, the exhibition’s accompanying catalogue serves as an enticing prelude to the show’s appearance in Brooklyn, where I plan to see it next spring. A lively, and handsomely illustrated volume, the book features an essay by McClusky, and an interview with Massaquoi, as well as colorful spreads and statements by each of the ten commissioned artists. In a recent phone conversation, McClusky shared with me her thoughts about this unique project, from its planning stages to its realization.

David Ebony: “Disguise: Masks and Global African Art,” seems to me to be one of the most unusual touring museum exhibitions out there. It has an extraordinary theme—high-tech masquerade?—plus it contains work by several of my favorite up-and-coming artists, such as Saya Woolfalk, Jacolby Satterwhite, and Ebony G. Patterson. Since I probably won’t get to see the exhibition until next spring in Brooklyn, I would like to ask, how well do you think the accompanying book represents the show?

Installation view of ChimaTEK: Virtual Chimeric Space (detail), 2015, at Seattle Art Museum, Saya Woolfalk, United States, b. 1979, installation with five costumes with 3-D masks and video, dimensions variable, Seattle Art Museum, Commission, 2015. © Seattle Art Museum, Photo: Nathaniel Willson.

Pamela McClusky: The book is a kind of forecast—promises of the work that is now part of the actual installation. You can think of it as a premonition. The catalogue, of course, had to be done far in advance to be ready for the exhibition, but some of the commissioned pieces came together only days before the exhibition’s opening. So the book foretells of the show, but doesn’t necessarily reflect precisely what is in it.

Ebony: What were you looking for when you commissioned the artists?

McClusky: Erika [Erika Dalya Massaquoi] and I did an open casting, looking for artists with a point of departure with African masks, masks and disguises in general, or a new way of framing how we look at disguise. We wanted to go in depth with a dozen or so artists rather than do a full survey of the subject.

Ebony: In your essay, you describe the exhibition as a unique form of performance. Can you say more about that?

Installation view of En Plein Air: Abduction II, 2014, at Seattle Art Museum, Jacolby Satterwhite, United States, b. 1986, C-print in artist’s frame, 84 x 60 in., loan from the artist and OHWOW Gallery, Los Angeles. © Seattle Art Museum, Photo: Nathaniel Willson.

McClusky: Artists are changing the way we think about what goes into galleries, and how works should be shown. I still often see exhibitions in museums and galleries that are kind of like isolation chambers, where everything is in its separate space or mount, about six or eight feet apart from each other. With this exhibition, there’s a bit of jostling with that expected model. It’s quite complex. There are things that ignite your senses, starting right from the beginning with motion sensors that trigger sounds; the entire show is orchestrated in a different way from what we usually see.

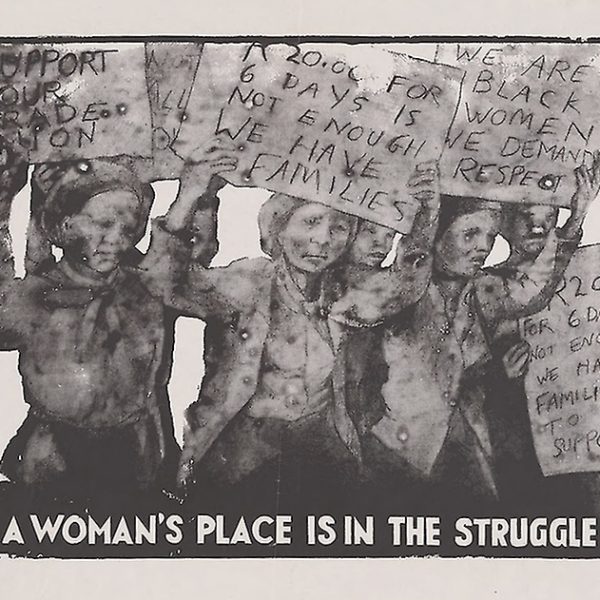

Of 72 Project (detail), 2012, Ebony Patterson, Jamaica/United States, b. 1981, digital prints on hand-embellished bandanas, 73 bandanas, 21 x 21 in. each, Commissioned by Small Axe Magazine and the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Arts Grants, Courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago. © Ebony Patterson, Photo courtesy of the artist and Monique Meloche Gallery, Chicago.

Ebony: You discuss at length in the book a performance by Alejandro Guzman that you saw in Chelsea, in 2013, The Fatalist, which made a big impression, moved you, and seems to be key to this exhibition.

McClusky: It was a performance that I came across on a trip to New York, where we were scouting for artists to include in a show that would be centered on masks, and the idea of disguise. In the center of a Chelsea gallery, there was what I called an odd piece, or a tall boxy sculpture that recalled a duck or a bull, with a glittery head, and rather crude construction. All the other pieces in the show were framed and hung on the wall. We were told that the object would do something, or would be part of a performance later in the week, so we returned.

Alejandro Guzman inhabited the piece as a kind of costume. He hid inside the sculpture, which spun periodically while making creaking sounds, and with streamers and mirrored fragments flashing.

Installation view of The Fatalist, 2013, at Seattle Art Museum, Alejandro Guzman, Puerto Rico/United States, b. 1985, wood, screws, chicken wire, casters, plastic, silicone, foam, plaster, Coroplast, mirrors, glitter, crystals, aluminum, copper, brass, bamboo, nkisi head figure, Nok beads, Polish beads, clothes, fabric, trim, oil paint, ink on paper, rabbit fur, elephant tusk, bull horns, 90 x 42 x 24 in., loan from the artist. © Alejandro Guzman, Photo courtesy of Susan Inglett Gallery, NYC.

Attendant performers engaged the audience in various ways, in a sequence of spontaneous gestures. The piece was evocative; it transported me to Africa. It reminded me of what happens in Africa in the spontaneous performances I’ve witnessed, which included a wide range of participants. The Fatalist is a piece in which the performer activates the imagination in a fresh way. You can’t predict where it will take you. In Alejandro’s work, I realized that there is hope for this kind of instinctive performance to happen in the U.S. more often.

Ebony: Is The Fatalist part of your show? Will it be at the Brooklyn Museum of Art?

McClusky: Yes. He has already been working with collaborators in Brooklyn, and has some ideas of how the work will be performed there. The Fatalist, incidentally, was part of a group show at Susan Inglett Gallery curated by William Villalongo, whose work is also included in “Disguise.”

Ebony: In the book, you write, “When the mask replaces masquerade, disguise is deflated.” Could you say more about that?

McClusky: The original context for masquerade is that the mask is just one part of an ensemble, an active agent in a sequence of events during a performance. In our museum, we have an extraordinary collection of African masks. But when a mask is displayed on a pedestal, it has no voice, no movement. It’s not part of disguise. It’s more like a captive insect. In fact, it was created with the intention of engaging all of our senses.

Installation view of An Ancestor Takes a Photograph, 2014, at Seattle Art Museum, Wura-Natasha Ogunji, United States/Nigeria, b. 1970, video, filmed in Lagos, Nigeria, Seattle Art Museum, Commission, 2015. © Seattle Art Museum, Photo: Nathaniel Willson.

Ebony: You are quite critical of the way most Western artists approach African masks, and how they incorporate them into their works. I am thinking particularly of your comments about Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’ Avignon (1907), and how so much is wrong with that image.

McClusky: Picasso loved African masks, of course. But he used them for his own purposes. The idea of depicting them as heads of naked women in a brothel would have been horrifying to most Africans of the time. They would have been outraged because with the mask comes a lot of responsibility. For Western artists, there was little sensitivity toward the way the mask was originally used. It’s a detriment that so often Westerners take what we want from other cultures, but neglect to talk to the ones who created the art, and made use of it to begin with. What you might think is sympathetic is actually quite insulting, or at least diminishing.

It’s still going on today; consider a work of popular culture like The Lion King. It is entertaining, but it has much more to do with Shakespeare than with African mythology. In our exhibition, African artists turn the tables on Western culture a bit; many of the pieces are critiques of Western culture from an African point of view. In some works we get a sense of moving into the future, and looking ahead at what is possible, or what could be.

David Ebony is currently a Contributing Editor of Art in America magazine. Among his books are Arne Svenson: The Neighbors (2015); Anselm Reyle: Mystic Silver (2012); Carlo Maria Mariani in the 21st Century (2011); Emily Mason (2006); Botero: Abu Ghraib (2006); Craigie Horsfield: Relation (2005); and Graham Sutherland: A Retrospective (1998). He lives and works in New York City.