An International Women’s Day Reading List

Today is International Women’s Day, a day to honor the women who have fought for political and social equality around the world. But even as we celebrate the courage, creativity, and resolve of women, we recognize that equality has not been attained, and we must all work together to achieve it. To that end, we’ve compiled an International Women’s Day reading list that both honors the political and economic advances of women in the American context and elucidates what needs to change in order for true equality to be realized.

We Shall Overcome traces the history of legal efforts to achieve civil rights for all Americans, beginning with the years leading up to the Revolution and continuing to our own times. The historical adventure Alexander Tsesis recounts is filled with fascinating events, with real change and disappointing compromise, and with courageous individuals and organizations committed to ending injustice.

Mary Wollstonecraft’s visionary treatise, A Vindication of the Rights of Woman, originally published in 1792, was the first book to present women’s rights as an issue of universal human rights. This edition of Wollstonecraft’s groundbreaking feminist argument includes illuminating essays by leading scholars that highlight the author’s significant contributions to modern political philosophy.

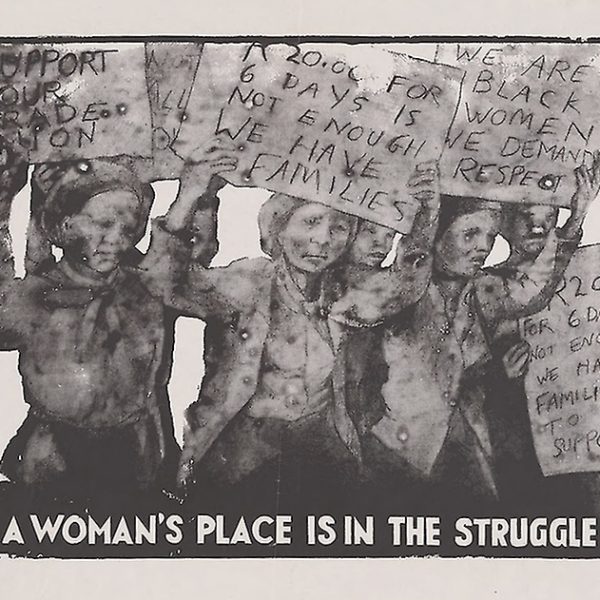

In Civil Disobedience, Lewis Perry examines the causes that have inspired civil disobedience, the justifications used to defend it, disagreements among practitioners, and the controversies it has aroused at every turn. Examining in detail campaigns for women’s equality, temperance, and labor reforms, Perry clarifies some of the central implications of civil disobedience that have become blurred in recent times—nonviolence, respect for law, commitment to democratic processes—and throughout the book highlights the dilemmas faced by those who choose to violate laws in the name of a higher morality.

f

f

f

f

f

Praised by the New York Times as “a feminist classic,” Sandra M. Gilbert and Susan Gubar’s The Madwoman in the Attic is a pathbreaking book of feminist literary criticism. This edition includes a substantial introduction by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar that reveals the origins of their revolutionary realization in the 1970s that “the personal was the political, the sexual was the textual.”

In Sister Citizen, Melissa V. Harris-Perry explores how African American women understand themselves as citizens and what they expect from political organizing. Harris-Perry shows that the shared struggle to preserve an authentic self and secure recognition as a citizen links together black women in America, from the anonymous survivors of Hurricane Katrina to the former First Lady of the United States.

Harriot Stanton Blatch (1856-1940), daughter of the famous suffragist Elizabeth Cady Stanton, played an essential role in the winning of woman suffrage in the United States. In Harriet Stanton Blanch and the Winning of Women’s Suffrage, Ellen Carol DuBois tells the story of Blatch’s life and work, in the process reinterpreting the history and politics of the American suffrage movement and the consequences for women’s freedom.

Erica Armstrong Dunbar’s A Fragile Freedom, the first book to chronicle the lives of African American women in the urban north during the early years of the republic, investigates how African American women in Philadelphia journeyed from enslavement to the precarious status of “free persons” in the decades leading up to the Civil War and examines comparable developments in the cities of New York and Boston.

In Wollstonecraft, Mill, & Women’s Human Rights, Eileen Hunt Botting offers the first comparative study of writings by Mary Wollstonecraft and John Stuart Mill. Although Wollstonecraft and Mill were the primary philosophical architects of the view that women’s rights are human rights, Botting shows how non-Western thinkers have revised and internationalized their original theories since the nineteenth century. Botting explains why this revised and internationalized theory of women’s human rights—grown out of Wollstonecraft and Mill but stripped of their Eurocentric biases—is an important contribution to thinking about human rights in truly universal terms.

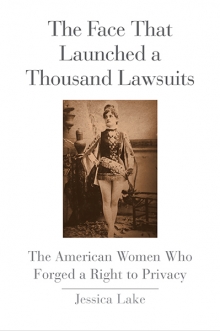

In The Face That Launched a Thousand Lawsuits, Jessica Lake documents how the advent of photography and cinema drove women—whose images were being taken and circulated without their consent—to court. There they championed the creation of new laws and laid the groundwork for America’s commitment to privacy. Vivid and engagingly written, this powerful work will draw scholars and students from a range of fields, including law, women’s history, the history of photography, and cinema and media studies.

In The Face That Launched a Thousand Lawsuits, Jessica Lake documents how the advent of photography and cinema drove women—whose images were being taken and circulated without their consent—to court. There they championed the creation of new laws and laid the groundwork for America’s commitment to privacy. Vivid and engagingly written, this powerful work will draw scholars and students from a range of fields, including law, women’s history, the history of photography, and cinema and media studies.

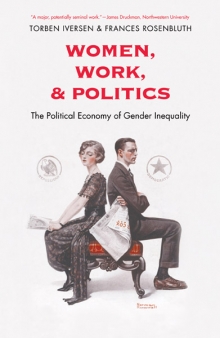

The first book to integrate the micro-level of families with the macro-level of national institutions, Women, Work, and Politics presents an original and groundbreaking approach to gender inequality. Looking at women’s power in the home, in the workplace, and in politics from a political economy perspective, Torben Iversen and Frances Rosenbluth demonstrate that equality is tied to demand for women’s labor outside the home, which is a function of structural, political, and institutional conditions.

The first book to integrate the micro-level of families with the macro-level of national institutions, Women, Work, and Politics presents an original and groundbreaking approach to gender inequality. Looking at women’s power in the home, in the workplace, and in politics from a political economy perspective, Torben Iversen and Frances Rosenbluth demonstrate that equality is tied to demand for women’s labor outside the home, which is a function of structural, political, and institutional conditions.

f

f

f

f

f

f