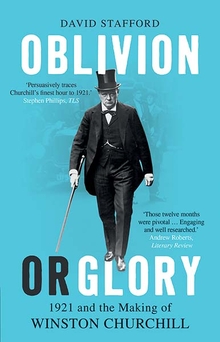

Oblivion or Glory

David Stafford—

Two things saved Churchill at this time of mid-life crisis. The first was his family. Its role in his life has often been underestimated. The constant and loyal support of his wife Clementine has certainly been well recognized, and the lives of their children, especially his tempestuous only son Randolph, are relatively well known. But there also existed the extended family of his mother, brother, sister-in law, aunts, uncles, and cousins, as well as Clementine’s own many relations, all of whom formed a large private clan on which he could rely throughout his life for support and comfort. He also inspired devotion from a network of friends to whom he remained profoundly loyal. One of these was Violet Asquith, the daughter of Herbert Asquith, who remained close to him until the end of his life. Shortly after he died, she published her memories (as Violet Bonham Carter) of their relationship under the title Winston Churchill as I Knew Him. ‘His friendship,’ she wrote, ‘was a stronghold against which the gates of Hell could not prevail. There was an absolute quality in his loyalty, known only to those within its walls . . . This inner citadel of the heart held first and foremost his relations – in their widest sense.’ It was to Violet that he confessed that he was ‘done’ as a result of the Dardanelles.

Thanks to this wider family network Churchill was introduced to his second great source of solace after the psychic wounds of Gallipoli. The loss of the Admiralty meant that he and the family had to leave Admiralty House, and they moved in with his younger brother’s family at 41 Cromwell Road, London, almost opposite the Natural History Museum. Behind the scenes, brother Jack was a constant source of advice and support to him throughout his life. Ironically, Jack was just then serving with the British forces at Gallipoli. So it was left to his wife Gwendeline (fondly known as ‘Goonie’) to look after their two young children and run the household. That summer, the two families jointly leased a property in the country known as Hoe Farm, near Godalming in Surrey, to which they would retreat for weekends. One day, Churchill was wandering disconsolately through the garden when he came across Goonie sketching with watercolours. After watching her for a few minutes he borrowed his nephew Johnnie’s paint box and got to work. Soon he began to experiment with oils, opened an account with an artists’ supply company in Covent Garden, and started making regular purchases of canvases, paints, and other artistic paraphernalia. It was the beginning of what would become a lifetime’s passion for painting, with some five hundred completed canvases to his credit. This was more than the amusing hobby of a great man, deserving perhaps of a footnote. On the contrary, it was a vital thread in the tapestry of his life that reveals much about his character.

It was at Hoe Farm, too, that the poet Wilfrid Scawen Blunt encountered him that same summer. Ten years before, he had been struck by Churchill’s sparkling wit, intelligence, and originality and by how much he resembled his father – only with more ability. ‘There is the same gaminerie and contempt of the conventional,’ noted Blunt, ‘and the same engaging plain-spokenness . . . ’ But at Hoe Farm, Blunt found a very different and more subdued Churchill, sitting under an old yew tree surrounded by members of the family while attempting to sketch his sister-in-law, Nellie. ‘There is more blood than paint on these hands,’ he abjectly told the poet. ‘We thought it [the Dardanelles] would be a little job, and so it might have been if it had begun in the right way and now all these lives lost.’ ‘Poor Winston,’ reflected Blunt, ‘I imagine that but for his wife’s devotion and his domestic happiness with his children and the support of a few relatives, he might have gone mad.’

From Oblivion or Glory by David Stafford. Published by Yale University Press in 2021. Reproduced with permission.

David Stafford is an adjunct professor at the University of Victoria and a renowned expert on Churchill. His former publications include Churchill and Secret Service, Roosevelt and Churchill,and Endgame, 1945.

Further Reading: