Reflections on the World of My Father

Nina Howe—

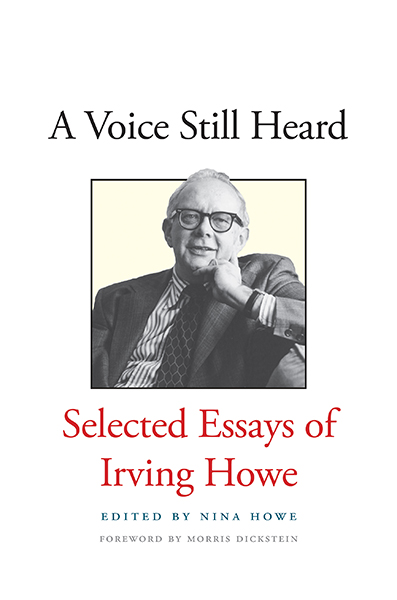

The experience of editing the book, A Voice Still Heard, a selection of essays by my late father Irving Howe, was for me an exploration into my father’s life outside the family home. My father was a private person; he did not talk very much about his childhood or later formative experiences at City College or in the army during World War II (he spent two years in Alaska), nor did he share a great deal about his work with me. During the 1950s and 60s, when he was building his reputation as a literary and political critic, I was a child and adolescent engaged in activities other than reading my father’s essays and books. After my parents were divorced, when I was about nine, my father and I maintained a very warm relationship that grew stronger once I was in my 20’s. At this time I began to read his work more seriously and I, as a voracious reader of fiction, began to rely on my father as a source of literary recommendations. In later years, when visiting New York, I would examine the stack of books on a small table next to Dad’s desk to see what he was reading and what novels he might recommend. Our joint love of literature, especially the American, European, and Russian schools, was one of the many strong bonds between us. Once he asked me if I could recommend any Canadian authors besides Margaret Atwood and I sent him an early collection of Alice Munro’s stories, nervously awaiting his response. When he declared her stories to be “very fine”, I felt relieved; no doubt he would have been pleased that she won the Nobel Prize for Literature last year.

The journey of curating this collection, together with the wonderful assistance of my son Nicholas, was, at least in part, a personal exploration about my father’s more public ideas and persona. It was a way for me to capture a more intimate view of how he thought, of the ideas that attracted his attention, and how he crafted his writing. As I read through the many pieces recommended by several very helpful individuals, I developed a deeper understanding of the role that democratic socialism played in his intellectual life. I have always been proud that he and Lewis Coser had founded Dissent magazine in the early 1950s at the height of the McCarthy era. Reading his political writings from that time until his death in 1993 provided a longitudinal view of the larger and enduring political themes in his writings and how intertwined they were with his literary interests. Throughout his life, my father was a caring and optimistic but ultimately realistic person; indeed he hoped for a “world more attractive.” Had his immigrant parents landed in Canada instead of New York, he might have entered politics as a member of the New Democratic Party (NDP), which is a social democratic political party. Stephen Lewis, whose interview with my father appears at the end of the book, was a leading member of the NDP. His father, David Lewis, was one of the party’s founding and intellectual architects. Today, the NDP is the official opposition in the Canadian parliament, which would have both pleased and surprised my father.

My father did not amass a collection of professional or personal papers. Shortly after his death, my brother, Nick, was contacted by several universities eager to receive such a collection, but were dumfounded to learn that there were no such papers. When my father finished an essay or a book, he apparently disposed of any drafts. Also, he did not keep any correspondence or papers related to Dissent. When my father died, Nick found only the essays in his desk that were published posthumously in A Critic’s Notebook, several of which are included in the present collection. The finished essays had a checkmark on the top of page one, apparently to indicate that they were complete, whereas several other essays were still being drafted, but were developed enough to be published. There was no personal correspondence found in his desk, and in fact I only have one personal letter from my father, written after I had experienced a bout of cancer; it is a very short but touching letter that I treasure.

While posted in Alaska during World War II, my father wrote a number of letters to my mother, but unfortunately the box in which they were stored went missing in a move at some point in the late 1940s. I have often wondered what he wrote her and whether the letters were drafted in a more personal tone than his more formal writing. He also sent my mother a list of 96 novels that he read during his posting, which clearly formed his own graduate education. In reading through the pieces with my son for this book, there are hints of the personal in several of the essays. Although he rarely directly wrote about himself, the experience he describes in “Strangers” about Jewish American immigrant youth growing up in the slums of NYC during the Depression and coming to terms with American literary figures like Emerson and Frost could surely only have been based on his own experience. Or the literary world he describes in “The New York Intellectuals” certainly speaks of his experiences, as probably did some of the chapters in World of Our Fathers, which we opted not to include in this collection. I felt that it was important for the reader to end the book with two pieces that provide a glimpse of the personal and emotional side of my father, which is why we included the moving piece on his conflicted feelings about the death of his own father, as well as the interview with Stephen Lewis in which Dad spoke of his childhood and youth. Both of these pieces struck a chord with me that I wanted to share with others.

Books reviews were in many ways the staple of my father’s life. Some were selected for the collection because they were about books that Dad had recommended to me, while others stood out for other reasons. I have a clear memory of a phone call from Robert Silvers while I was visiting on Cape Cod in the summer of 1963, at the height of a strike at the New York Times. Silvers was in the process of founding the New York Review of Books and asked my father to write a book review. I remember how excited my father was when he got off the phone. In looking up that first issue, one can only admire the incredible list of authors that Silvers published, including a review of The Partisan Review Anthology by my father.

Curating this collection with the dedicated and valuable assistance of my son, Nicholas, and with the contributions of other family members has been a moving and proud experience for me. I only wish my father were still alive so I could share some of my perceptions and thoughts on his work with him and to bask in his pride for the work that his grandson and I did. But if he were still alive, I probably would not have edited this collection of his work because he would have likely done so himself. In some ways, this is a bittersweet moment for me but also a deeply enlightening and gratifying one.

Nina Howe is Concordia University Research Chair in Education and a member of the university’s Faculty of Arts and Science. The daughter of Irving Howe, she recently edited a collection of her father’s essays entitled A Voice Still Heard.

Further Reading: