Black Mountain College: A Progressive Education

The “landmark,” “deeply researched,” “curatorial triumph” of an exhibition Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933-1957 opens today, February 21st, at UCLA’s Hammer Museum, having finished its successful run at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. It “is a show not only every art-school student in this region but every artist, every student, every teacher, and every former student will profit from seeing” (says Sebastian Smee in the pages of the Boston Globe). A book of the same title accompanies the exhibition, and it is every bit as magnificent as the show. The book’s fresh approach and rich illustration program convey the atmosphere of creativity and experimentation that was unique to Black Mountain College, and that served as an inspiration to so many. We’re delighted to share an excerpt from the book, an essay by co-curator Ruth Erickson entitled “A Progressive Education.”

The “landmark,” “deeply researched,” “curatorial triumph” of an exhibition Leap Before You Look: Black Mountain College, 1933-1957 opens today, February 21st, at UCLA’s Hammer Museum, having finished its successful run at the Institute of Contemporary Art in Boston. It “is a show not only every art-school student in this region but every artist, every student, every teacher, and every former student will profit from seeing” (says Sebastian Smee in the pages of the Boston Globe). A book of the same title accompanies the exhibition, and it is every bit as magnificent as the show. The book’s fresh approach and rich illustration program convey the atmosphere of creativity and experimentation that was unique to Black Mountain College, and that served as an inspiration to so many. We’re delighted to share an excerpt from the book, an essay by co-curator Ruth Erickson entitled “A Progressive Education.”

What you do with what you know is the important thing. To know is not enough. —John Rice

There were no letter grades at Black Mountain College, nor were there required courses, set curricula, standard examinations, or prescribed teaching methods. The responsibility of education resided with the students, who advanced from the junior to senior division and ultimately graduated by completing, as the first college catalogue described, “comprehensive tests of [a student’s] failure or success in meeting responsibility.” These individually tailored exams, which students undertook only when they felt prepared to do so (meaning that very few students ever graduated from Black Mountain), posed a series of diverse questions: “What did you learn from our studies with fall leaves?” “What do you think should be done about the Negro problem in the United States?” “Suppose that your task was to design a piano cover, what factors would you have to consider?” “What do you think we will laugh at in twenty years from now that we take very seriously today?” Such questions sought to test not students’ knowledge base but their critical, creative, and responsive acumen—that is, their ability to construct a color study, discuss political rights, and arrange plants in a garden with equanimity and self-reflection.

John Rice, n.d.

When John Rice established Black Mountain College in 1933, he sought to create a school that dissolved distinctions between curricular and extracurricular activities, that conceived of education and life as deeply intertwined, and that placed the arts at the center rather than at the margins of learning. Study at the college thus consisted of traditional liberal arts subjects—literature, biology, mathematics, foreign language, drama, music, the visual arts, and so forth—as well as participation in the college’s functional operations and community. For Rice, education was registered not by grades or other standard criteria but in a heightened desire to learn and to question, which would lead students to an expanded aptitude for solving a range of problems and to a richer sense of self. The college’s only examinations signal these priorities, testing students’ capacity to engage imaginatively with the issues—philosophical, social, and practical—confronted in contemporary life. At Black Mountain, Rice told the writer Louis Adamic, “our central and consistent effort is to teach method, not content; to emphasize process, not results; to invite the students to the realization that the way of handling facts and himself amid the facts is more important than facts themselves.”

Rice’s boyhood education at the Webb School in Buck Bell, Tennessee, informed his vision. That school’s founder, John Webb, first modeled the pedagogy that Rice would come to praise and emulate. As Rice recalled in his autobiography, Webb’s “mind was fertile with ways for bringing boys to knowledge. . . . His pupils acquired respect for their own capacity, for he made each of them an artist for the moment, with his own private goal.” Employing a Socratic method—posing questions and encouraging students to discover their own paths to answers—rather than conveying information directly, Webb inspired Rice’s approach as a teacher. This formation not only inclined Rice to uphold the ideals of progressive education but also instilled in him skepticism of the soft intellectualism that befell many progressive initiatives. “When I bore the dubious title of educator and at last was tagged with the still more dubious ‘Progressive,’” Rice recalls, “I visited schools and listened to breathless accounts of the latest things. I could match them point by point from the Webb School I knew as a student and go them one better—two better, for the school had both order and intellectual backbone.”

By the 1930s, John Dewey’s proposals for progressive education, promoting experimental and innovative learning through self-directed experiences in and outside the classroom, led to the blossoming of numerous institutions. Indeed, Rice first met Dewey in 1931, when Dewey came to Rollins College to chair the Conference on Curriculum for the College of Liberal Arts, a meeting that brought together representatives from many liberal arts colleges that had emerged in the 1920s and 1930s to enact models of progressive education. These included Sarah Lawrence (opened in 1926), Antioch (reorganized in 1921), and Bennington (opened in 1931 by progressive educator William Kilpatrick). Dewey had argued since the late 1890s that schools served an essential social function by cultivating freethinking and well-informed individuals who would fully participate in democratic society. In Democracy and Education, he wrote, “The criterion of the value of school education is the extent in which it creates a desire for continued growth.” Through Dewey, Rice discovered a means of linking his convictions about pedagogy with his commitment to democracy, and at Black Mountain Dewey found an example of his educational philosophy in practice.

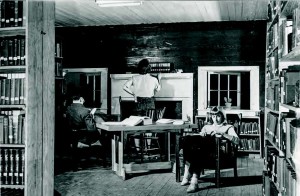

Black Mountain College library, n.d.

Dewey visited Black Mountain multiple times, ultimately joining the board of advisers and donating hundreds of books to the college library. While he never spoke in detail about the college, Dewey understood it to be deeply intertwined with democracy. In a letter to Rice following his first visit in 1935, Dewey wrote, “No matter how the present crisis comes out, the need for the kind of work the College does is imperative in the long-run interests of democracy. The College exists at the very ‘grass roots’ of a democratic way of life.” Like other progressive schools of higher education, Black Mountain College offered a more horizontal model of governance, empowering faculty instead of trustees to lead the school and involving the entire school community in discussions about major decisions. Furthermore, teaching staff, their families, and students shared housing, so that, as the first college catalogue explained, “the relation is not so much of teacher to student as of one member of the community to another.”

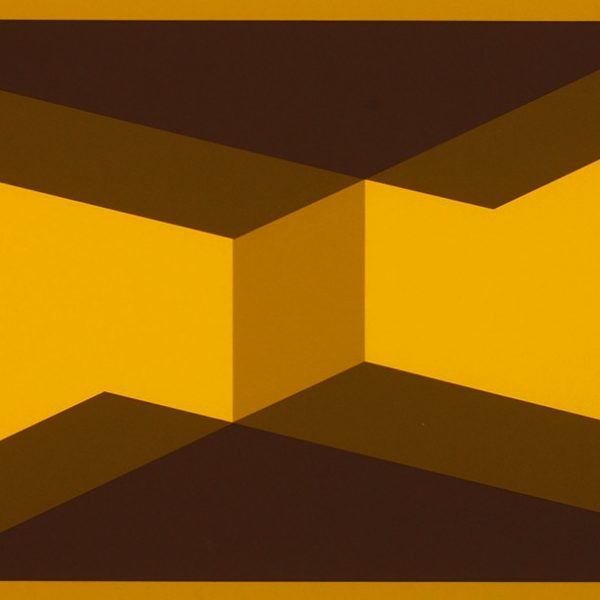

What most distinguished Black Mountain from other schools was the vital role that the arts played in the college’s democratic aims. Both Rice and Dewey valued the creative and emotional aspects of human development and believed that art—or the “art experience”—was essential for nurturing an individual’s capacity to participate in a democracy. The arts, according to Rice, are “least subject to direction from without and yet have within them a severe discipline of their own.” An art experience, as Dewey outlined in Art as Experience (1934), was about discovering and respecting the integrity of one’s materials. Black Mountain College literature echoed this sentiment: “Through some kind of art experience, which is not necessarily the same as self-expression, the student can come to the realization of order in the world; and, by being sensitized to movement, form, sound, and the other media of the arts, gets a firmer control of himself and his environment than is possible through purely intellectual effort.” The theory is that the process of making art hones not only observation but also judgment and action, so that students who acquire intelligence through art both notice what is happening around them and develop individual responses to it. In Rice’s words, “The artist thinks about what he himself is going to do, does it himself, and then reflects upon the thing that he himself has done.” By encouraging both self-reflection and the translation of thought into action, pedagogy at Black Mountain began with art to end with democracy.

Ruth Erickson is associate curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Boston.

All images courtesy of the Western Regional Archives, State Archives of North Carolina.