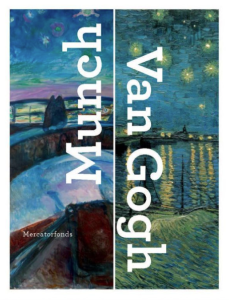

Munch: Van Gogh

“During his short life, Van Gogh did not allow his flame to go out. Fire and embers were his brushes during the few years of his life, whist he burned out for his art. I have thought, and wished, that in the long term, with more money at my disposal, like him, I would not let my flame go out, and with a burning brush paint until the end.” — Edvard Munch, 28 October 1933

Ivy Sanders Schneider–

Although they never met, Vincent Van Gogh and Edvard Munch lived parallel lives. Both sought and found, in art and nature, a higher spiritual power. Both respected and imitated artists like Paul Cézanne, Edouard Manet, Georges Seurat, and Paul Gauguin. Both are known for work characterized by visible brushstrokes, vibrant colors, and violent emotion.

Although both have been recognized as fathers of modern art, it was only in 2015 that the two became subjects of an exhibition dedicated solely to their artistic relationship. They have been displayed in group shows and galleries since 1912, but the exhibition Munch : Van Gogh, a collaboration between the Munch Museet and the Van Gogh Museum, (which produced the accompanying book of the same name) represents the first ever formal comparative study.

Although both have been recognized as fathers of modern art, it was only in 2015 that the two became subjects of an exhibition dedicated solely to their artistic relationship. They have been displayed in group shows and galleries since 1912, but the exhibition Munch : Van Gogh, a collaboration between the Munch Museet and the Van Gogh Museum, (which produced the accompanying book of the same name) represents the first ever formal comparative study.

Edvard Munch (1863-1944) was born in Norway, and Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890) in the Netherlands. They both grew up in religious protestant families, under dominant fathers, who ensured the bible was an enduring presence in the life of each boy. In 1885 Munch moved to Paris, and in 1886 Van Gogh followed, but Munch had already moved away. Still, both lived in the Montmartre neighborhood, saw the same sights, and socialized in the same circles. Throughout their lives, each carefully documented his journey, revealing parallels not just in the basic facts of their lives, but in their personal thoughts, and attitudes towards art making.

Van Gogh primarily wrote letters, whereas Munch kept diaries and notebooks, sometimes with the intent to publish. The texts of both reveal convergent inner lives, which help explain their convergent bodies of work (both would produce a version of Starry Night and The Scream). Both artists blurred the lines between art and life, painting and literature. Van Gogh wrote, “books and reality and art are the same kind of thing for me” (Letter 312, February 11, 1883). Munch, in turn, moved between mediums, describing his monumental Frieze of Life as a poem “about life, about love and about death.” Additionally, in loose notes his archive categorizes as “Aphorisms related to art,” Munch wrote,

All art like

music must be created

with one’s lifeblood –

Art is one’s lifeblood

For him, as for Van Gogh, reality was fodder for art, and art acted as a force that inspired him to continue participating in reality. Both men fully dedicated their lives to their work, giving up expectations of traditional romantic love and happiness, devoting themselves to this higher calling instead. Although their painting often took the place of human interaction, it also facilitated it. In a notebook, Munch wrote,

On the whole

Art comes

from one human being’s compulsion

to communicate to

another

According to Munch, art exists to communicate lived experience. Van Gogh, too, fully believed this, as his hundreds of letters to his brother, Theo, and fellow artists, can attest. He wrote about his daily routine, his health, his finances, but primarily he wrote about, and sketched images of, his art, or art that he had seen. He also wrote about the way in which art serves to reproduce reality. In a letter to fellow artist Emile Bernard, Van Gogh described art in the wake of a hospitalization. Although his work had become abstracted, he wrote how, “by working very calmly, beautiful subjects will come of their own accord; it’s truly first and foremost a question of immersing oneself in reality again” (Letter 822, November, 26, 1889). For Munch, art was a way to convey one’s perceived reality. For Van Gogh, art was a way to perceive reality again. Still, for both it was “lifeblood,” what they live for, and what allows them to live.

In the same fragment in which Munch ruminated on art as a facilitator of communication, he mused on the act of writing about art. He said,

To explain a

picture is impossible

– It is precisely

because one cannot

explain it in any other

way than it has been

painted.

This was an issue with which Van Gogh grappled for the entirety of his writing life. He communicated primarily through words, and often sketches, and promised real future encounters with the artwork. He often, instead, would describe the emotional feeling of an artwork, or else what he was attempting to do. In the previously referenced letter to Bernard, Van Gogh wrote of the evocative simplicity of the Italian Renaissance painter Giotto. Van Gogh described, “the expressions in it of pain and ecstasy are human to the point that… you feel you’re in it — and believe you were there, present, so much do you share the emotion” (Letter 822, November 26, 1889). Here, even as he attempted to replicate the effect of an artwork, the highest praise he could give is that the artwork felt real, and excited him not just visually, but emotionally and psychologically.

Van Gogh and Munch’s mental lives and personal journeys were deeply linked to the paintings they created. For them, parallel thoughts often created parallel works. Both artists produced a Starry Night, Munch in the 1920s (Starry Night), and Van Gogh in 1888 (Starry Night over the Rhone), which Munch almost certainly saw. Both produced uneasy, despairing Screams (Van Gogh’s named The Bridge at Trinquetaille), depicting dark figures on bridges, against sickly yellow water and sky. Finally, both produced emotionally charged portraits of their homes. Van Gogh produced The Yellow House (1888) as he looked forward to his friend Gauguin’s arrival. In the painting the house practically glows in hopeful anticipation. In contrast, Munch produced Red Virginia Creeper (1898-1900), which shows his home covered in a thick red vine, which seems to be bleeding in anguish. For both, violent emotion was a facet of their everyday lives, which spilled over into their work. Their physical and emotional realities blended together, and infused their art. Painting and writing provided outlets for and respites from lonely lives experienced perhaps too deeply, and now, unite the solitary pair.

The joint exhibition ran from September, 2015 to January, 2016, but many of the works are on display individually in the museums dedicated to each artist — the Munch Museet in Oslo, and the Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam.

The book Munch: Van Gogh, compiled by Maite Van Dijk, Magne Bruteig, and Leo Jansen, is an exhibition catalogue and more, offering comparative artistic timelines, critical essays, and full page color illustrations of their paintings, sketches, and letters, tracing two lives and legacies that run in parallel.

The writings of both artists represent a treasure trove for archivists. Munch’s archives include 5839 letters (or 13,000 manuscript pages), 68 of which (totalling 1100 manuscript pages) have been translated into English. Van Gogh’s archives contain 902 letters and 25 additional loose sheets and drafts, all of which have been translated into English. For more of Van Gogh’s writings, Ever Yours: The Essential Letters includes transcriptions and translations 265 of his letters, in addition to over 80 images of the letters and sketches themselves.

Ivy Sanders Schneider, a rising senior English major in Yale College, is an art & architecture intern at Yale University Press.