A Maya Child’s Tale: The Origin of the Sun

Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos—

In his field diary entry of October 30, 1960, ethnographer Marcelo Díaz de Salas wrote down a brief story that he’d been told by Miguelito, a young boy about 11 years old, in the Tzotzil Maya village of Venustiano Carranza (located in the highlands of Chiapas, Mexico): When the world was in darkness, the old men were seated around a fire, but didn’t dare to throw themselves in the flames. A little boy, who was the son of the moon, came and threw himself into the pyre, and emerged as the sun.

Surprised and fascinated, Díaz de Salas asked Miguelito where had he heard the story. The boy answered, “from the old people.” The ethnographer may have wondered whether modern school teachers might have introduced the story to the village, but he noted that his young informant had never attended school. He came to realize that this was a version of a myth about the origin of the sun that he knew from narratives compiled in early colonial Mexico, some of them written in the Nahuatl language of the Aztecs. In those versions, the sickly god Nanahuatl (whose skin was covered with pustules and whose very name means “buboes”) proved to be the only one capable of throwing himself into a blazing pyre, after a handsome and rich rival had failed in the attempt. Nanahuatl absorbed all the heat and came out as the sun, while the humiliated contender threw himself in the tepid ashes and became the moon. But how to explain the myth’s persistence among the Tzotzil Maya in this remote village? Was it introduced by the conquering Aztecs, who expanded their empire into southern Chiapas in the late fifteenth century? Is there any indication that the story was known to the Maya in more ancient times?

Díaz de Salas’s premature death relegated much of his work to obscurity. A couple of years ago, I came across his report and realized the importance of Miguelito’s tale for my research on ancient Maya religion and mythology. I was interested in the correlates between the mythical characters represented in ancient Maya art and those of early colonial and modern narratives. Regrettably, our sources are very limited, and our best records of Maya myths come from texts that were written in the early colonial period. Chief among them is the Popol Vuh, a literary masterwork composed around 1550, which recorded a wealth of mythical narratives from the K’iche’ Maya of highland Guatemala. In addition, modern Maya peoples, including the K’iche’ and Tzotzil, preserve oral narratives of pre-Hispanic origin, such as Miguelito’s story of the origin of the sun.

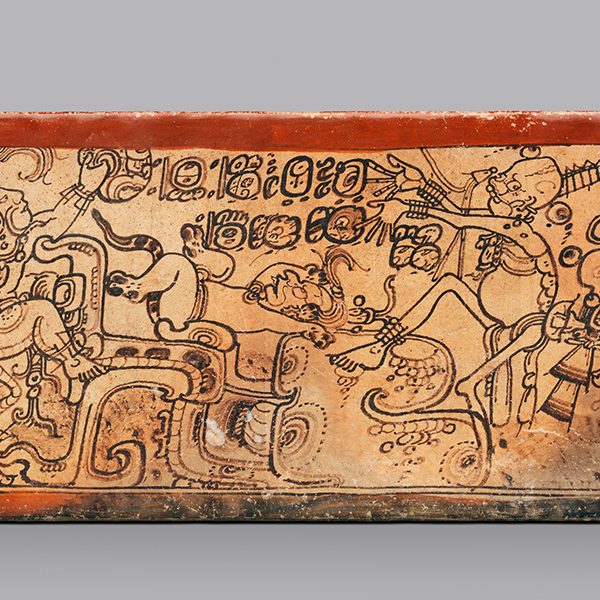

Examining numerous representations of mythical characters in Maya art, I noticed a fairly obvious, but tantalizing clue: a young god that was frequently portrayed in Classic Maya ceramic vessels (created between A.D. 300 and 900) had black spots on the face and body. Since they are also found on death gods, the spots are commonly associated with decomposing flesh. Sometimes surrounded by red halos, the spots of the Maya god were indeed close to the pustules or buboes that afflicted Nanahuatl, the miserable god who became the sun in Postclassic Aztec myths. I started thinking that the ancient Maya knew versions of this myth, which may or may not have featured the god’s fiery death.

Detail of the Blom Plate, Late Classic, lowland Maya area. Museo Maya de Cancún, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Nearly identical spotted gods shoot their blowguns at the Principal Bird Deity. Photo courtesy of Guido Krempel.

This was all the more intriguing because, in path-breaking work published in the 1970’s, Michael D. Coe suggested correspondences between the ancient Maya spotted god and the “Hero Twins” of the Popol Vuh. In the colonial K’iche’ version, a mythical pair of brothers defeated the monstrous creatures that reigned before the sun came out, and punished the death gods who had killed their father. The Popol Vuh did not describe them as suffering from skin ailments, but like Nanahuatl and the child hero of the Tzotzil myth, the Hero Twins met a fiery death by throwing themselves into a fire pit, came back to life to overcame their enemies, and finally rose to the sky as the sun and the moon.

The earliest known representations of the Maya spotted god appear in mural paintings at the site of San Bartolo, dating back to 100 B.C. Clearly, the belief in ailing gods who suffered from sores or pustules was very ancient, and it was not introduced to Maya mythology by late peoples from highland Mexico. But neither can we assume that it was the other way around, and that the Aztec adopted their myths from Maya models. Instead, I realized that the ancient Maya gods, their colonial K’iche’ and Aztec counterparts, and the heroes of modern myths derived from ageless roots. Storytellers recounted endless variations of the myths of the origin of the sun since remote times, long before the earliest pictorial or textual records that have reached us. Their stories were not identical to each other, and each narrator elaborated on some details while omitting others. In every version, the first sunrise was a key event that marked the beginning of an era, and made the world inhabitable for human beings.

The Maya artists who painted the San Bartolo murals, and the early colonial writers of the Popol Vuh knew versions of the myth. They foreshadowed the old people who told the story to Miguelito, many centuries later in highland Chiapas.

Oswaldo Chinchilla Mazariegos is assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Yale University.