Disraeli, de Rothschild, and the Struggle to Admit Jews to Parliament

Rosemary Ashton—

What was it like to live in London through one of the hottest summers on record, with the River Thames emitting a sickening smell as a result of the sewage of over two million inhabitants being discharged into the river and floating up and down with the tide, never being dispelled? What did those living or working near the Thames—including members of parliament sitting in stifling chambers in Westminster, just above the “blackish-green” mass and nauseous stench—do when they found their circumstances intolerable? What did the newspapers say?

As it happens, the summer of 1858, when the mercury hit 94.5ºF in the shade on the hottest day, 16 June, was a busy time for the Tory government of Lord Derby. His party had come to power in February, after the unexpected resignation of the popular Liberal Lord Palmerston, and Lord Derby was governing without a majority. He and his next-in-command, Benjamin Disraeli, the chancellor of the Exchequer, were attempting to get a number of important, far-reaching measures through before the summer recess, which was due to start at the end of July. There was the India Bill, which took the government of India under direct control at Westminster by abolishing the chaotic and unfair regime of the East India Company; the Medical Bill, which would regulate medical education and practice; most importantly and urgently, the Thames Purification Bill, by which a recalcitrant parliament was finally persuaded (partly by the stench and partly by Disraeli’s brilliance in debate) to legislate for the cleansing and embanking of the river. Within seven years the unhealthy muddy shores of the Thames were given fine stone embankments on both sides, the sewage was taken underneath them to outfalls east of London, and part of the world’s first underground railway was included in Joseph Bazalgette’s monumental engineering project.

Another ground-breaking measure was the Oath of Abjuration Bill, better known among the public as the “Jew Bill,” since the main point at issue was the passage to allow Jews to sit in parliament without having to swear “on the true faith of a Christian.” Bills had been brought forward by both liberals and conservatives year after year, ostensibly to remove absurd outdated clauses in the parliamentary oath such as that abjuring allegiance to the descendants of (Catholic) King James II, whose line had long been extinct, but in fact in order to remove the clause that had prevented Lionel de Rothschild from taking his seat in parliament, despite having been first elected as a member for the City of London in 1847. Many bills had been brought over the years. They passed in the House of Commons but were inevitably defeated by the bishops and others sitting in the House of Lords, out of plain religious bigotry in many cases, and out of a worry about Jews being allowed to legislate on matters relating to the established Church of England.

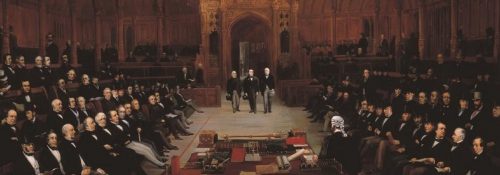

In 1858 the Bill finally succeeded, though only in part because of the prominence of the Jewish-born Disraeli in government. Disraeli had been baptised a Christian as a teenager, and—partly because he aspired to the highest office, partly because he was aware of a general low-key antagonism towards Jews in British society—he did not seek prominence in securing the rights of his friend Rothschild. Surprisingly, it was the patrician Lord Derby, fourteenth of his noble line, who acted most decisively to right the wrong. On 9 June, he wrote a “Confidential Circular” to his fellow Tory lords, expressing his unease about the embarrassing difference between the two houses of parliament on this ever-recurring question. He urged them to accept a compromise, namely that Jews could be accepted into the lower house, the Commons, while the upper house, the Lords, could continue to resist having them in their midst. There was juggling and toing and froing both in front of and behind the scenes until the Lords finally conceded on 1 July that the Commons could bring in an act to allow Jews to sit in their house. Rothschild was introduced to the Commons on 26 July, despite a last-ditch attempt by a few ultra-conservative objectors. As several newspapers noted, Derby and Disraeli presided over a remarkably reform-minded government. “Can we trust the evidence of our senses when we see a Tory millennium inaugurated by the admission of the Jews?” asked The Times. “What next?”

“Lionel Nathan de Rothschild introduced in the House of Commons on 26 July 1858 by Lord John Russell and Mr Abel Smith” by Henry Barraud, 1872; licensed for use on the public domain by The Rothschild Archive.

After all the troubles over successive bills, this one caused no shock or horror among the newspaper-reading public. Newspapers—morning, evening, weekly, national, and local—had multiplied several-fold since the passing in 1855 of the last so-called “taxes on knowledge,” paper and stamp duties which had kept newspapers out of the reach of the literate working class. Penny newspapers now abounded. Thanks to the digitization of the British Library’s vast collection of Victorian newspapers, historians can now search both widely and deeply for evidence of the attitude of the fourth estate towards the events of the day. Letters to the editor tell us what readers thought too. There was very little nastiness about Rothschild’s acceptance into parliament. Most papers, including even the satirical Punch (which was not averse to caricaturing Disraeli along racial lines), praised the Derby government for righting a wrong, and ridiculed the Lords for its foolish intransigence. While the ultra-conservative St James’s Chronicle attacked Rothschild as a hypocrite playing an anti-Christian game while appearing “with professions of religious liberalism upon his lips,” the Illustrated London News was scathing about the Lords’ apparent terror that a flood of Jews would rush into parliament. Yes, said the paper sarcastically, the number of likely representatives had already doubled from one, Rothschild, to two, with Rothschild’s cousin-in-law David Salomons, the first Jewish lord mayor of London, likely to be the next Jew to take his seat. (Salomons was duly elected the member for Greenwich in the 1859 general election, and Lionel’s younger brother Mayer de Rothschild took his seat too, thus bringing the number of Jewish MPs to three.)

If further proof were needed that the general population of London welcomed, or at least did not object to, the admission of Jews to parliament, it comes perhaps in some of the end-of-year Christmas pantomimes, with their joking response to the year’s events. One, Tit-Tat-Toe, performed in a small theater in humble Whitechapel, in London’s poor east end, celebrated Rothschild’s arrival as an example of “brave old England” welcoming “the right men in the right places.”

Rosemary Ashton is Emeritus Quain Professor of English Language and Literature, University College London. She is author of ten previous books and a fellow of the British Academy and of the Royal Society of Literature. She lives in London.

Further Reading

Featured Image: “Lionel Nathan de Rothschild, 1835” by Moritz Daniel Oppenheim, licensed for use on the public domain by the National Portrait Gallery.