Gore Vidal: Some After Words

On July 31, 2012, Gore Vidal died at his home in in the Hollywood Hills section of Los Angeles, where he had moved in 2003, the same year that Yale University Press published his acute observations on our founding fathers in the acclaimed Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson. In The New York Times the next morning, Charles McGrath penned his obituary, referring to Vidal as “the elegant, acerbic all-around man of letters who presided with a certain relish over what he declared to be the end of American civilization.” In this afterwards appended to Inventing a Nation, Vidal reflected upon the historiography entailed in writing about the early American republic—and a revealing conversation with his step-brother-in-law, President John F. Kennedy, in which he relayed how he conceived of the founding ethos of the American project as well.

Gore Vidal—

I am at the end of the space allotted. Since I have already described the most important, not to mention ambiguous, deed of Jefferson’s career, the Louisiana Purchase, I leave you with President John Adams’s great-grandson Henry Adams and his nine volume History of the United States of America During the Administrations of Thomas Jefferson and James Madison which was, at least for my generation, the essential—and certainly most witty—analysis of these formative years. In fact, the actual physical possession of those volumes was, for many of us, totemic. Years ago I asked the critic Elizabeth Hardwick if her divorce from poet Robert Lowell had been in any way difficult. “Oh, not at all,” she said, “except, of course, the usual intellectuals’ quarrel over which of us should get Henry Adams’s history.”

In the early seventies, when I was writing a book about Aaron Burr, I read the standard—and not so standard—texts of the day. These included Dumas Malone’s multivolume life of Jefferson. In my youth, I was fascinated by dramatic contradictions in character; in age, I am far more interested in those consistencies wherein lie greatness like Washington’s throughout his career, or overwrought conscience like Adams’s, throughout his. First time around, Dumas Malone annoyed me with his denial that Jefferson could not have had children by his slave Sally Hemings because no gentleman would have done so in the South, and as he was the greatest gentleman of Virginia . . . On this weak syllogism, a false character was constructed.

I am now more moved by Jefferson and the Nullification Resolutions (even in Dumas Malone) where Jefferson’s inner consistency about maintaining liberty within a state suddenly turned onerous comes up sharply against the problem of what to do when a heretofore virtuous republican government gets the votes in the two houses of Congress as well as that of a chief executive willing to collude with them in an assault on the Bill of Rights. Inevitably, Jefferson would think that if the States had not the right to nullify the central government’s tyrannous acts, they should leave the Union.

In 1860 the South thought that as each of their states had entered the Union voluntarily each had the right, using Jefferson’s own language, to secede on grounds similar to his: “When in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and of nature’s God entitled them, a decent respect to the opinion of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.” So far so good. Certainly an elimination of the First Amendment in itself would be a sufficient cause for secession or even rebellion.

But the great contradiction comes a few lines later. Jefferson lived with it uncomfortably for all his life, while the South spent four years dying with it on a hundred battlefields: “We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal: that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights: that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” But as of 1776 most African-Americans lived in slavery, and, in any case, each was counted in the Constitution itself not as a person but as a fraction of a whole person—which could only be, for purposes of citizenship, a white man. The various Indian tribes and nations were excluded from many inalienable rights, as were all women, who could not vote, or like those of us brought up in the District of Columbia (until we moved away).

The exuberantly expansionist Jeffersonian generation kept at bay the contradiction. Lincoln sidestepped the real issue—slavery—by moving the matter to what he took to be a higher plane, the integrity, the indivisibility of the Union. Secession, as a solution, was successfully put down. But what about those wrongs that neither federal nor state governments would put right? Enter John Marshall.

On December 16, 1800, soon-to-be former President Adams offered the chief justiceship to John Jay, who had once held—and relinquished—the post. The current chief justice was resigning due to ill health. Jay’s response to Adams was quick. “I left the bench perfectly convinced that under a system so defective it would not obtain the energy, weight, and dignity which, as the last resort of the justice of the nation, it should possess.” He said, no. Plainly actual “original intent” of the Constitution did not impress the first chief justice.

Since Republicans were not appointed federal judges during the first dozen years of the republic, the victorious Republican Party was all set to redress the balance. But Adams’s term did not end until March 4. He now had three months in which to appoint Federalists to the judiciary, leaving a lasting mark on the new government. On January 2, 1801, the lame duck Federalist majority in the House passed the New Judiciary Bill, authorizing new judges. That same day, Adams, without consulting Secretary of State Marshall, sent his name to the Senate for confirmation as chief justice of the United States. A week later the unprotesting Marshall was confirmed.

On February 4, Adams began to appoint a quantity of judges and justices of the peace, U.S. marshalls, attorneys, clerks, and sixteen circuit courts, each complete with Federalist judge. By March 3, at 9:00 P.M., with Marshall’s help, the job was done.

Meanwhile, Jefferson, in ecumenical mood, had written Marshall a note, “May I hope the favor of your attendance to administer the oath?”

March 4 was Jefferson’s inaugural day. Adams was not a good sport: some hours before he had started on his way back to Massachusetts and so he missed the dramatic moment when the two cousins, Jefferson and Marshall, faced each other in the only completed section of the Capitol at Washington, the Senate chamber.

Arguably the great division in American political life has been between the original Federalists and Republicans (they keep changing their names, even assuming one another’s identity, as circumstances and opportunity require). Their polar aspects, for those who enjoy personalizing the abstract, are Hamilton and Jefferson. Hamilton: “A national debt, if not excessive, will be to us a national blessing.” Today’s Hamiltonians have beatified our present nation with a debt undreamed of by Hamilton, who also took the Federalist dark view of democracy: The people is a great beast. Opposite to Hamilton is the benign Jefferson who assured us that, simply by birth, we have (his original words) “inalienable rights among which are the preservation of life and liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” That the actual pursuit of happiness is, in and of itself, the only true happiness that most of us will ever know might be the Puritan Adamsian gloss on what was more Jefferson’s great daydream than any working political philosophy. More to the point, Jefferson versus Marshall was to be the great drama that, to this day, divides us.

Before the election, Marshall was one of the extreme Federalists who enjoyed calling the Republicans “Democrats.” A very bad word indeed since it was associated with France’s bloody terror in the days of the Jacobin ascendancy, now swept away by First Consul Bonaparte, soon to be Emperor-dictator of the French. The morning of March 4, Marshall started a letter to Pinckney: “The Democrats are divided into speculative theorists and absolute terrorists. With the latter I am disposed to class Mr. Jefferson.” After the inauguration, he concluded his letter. “I have administered the oath to the Presd. His inauguration speech . . . well judged and conciliatory . . . is in direct terms giving the lie to the violent party declamation which has elected him, but it is strongly characteristic of the general cast of this political theory.”

There was continuing Republican criticism of Adams’s “midnight judges.” Meanwhile, Marshall was diplomatically silent on political issues of the day. Instead Marshall began a restructuring of the Court. Henceforth, the chief justice himself would, with few exceptions, deliver the Court’s opinion. Since no one in charge had thought of the Court as needing a courthouse, the Senate generously lent them a committee room on the main floor of the Capitol. (Later the Court was tactlessly moved to the basement.) In Marshall’s spare time, in those happy days abundant, he was busy negotiating with the publisher of what would become his vast biography of Washington. It was during this time that the fruit, as it were, of his joint work with Adams appeared before the Supreme Court.

On March 2, forty-two men, appointed by President Adams as justices of the peace for the District of Columbia, had been confirmed by the then-Federalist Senate; Marshall, as secretary of state, had also signed their commissions. Marshall’s successor at State, James Madison, came across the file and was duly annoyed. The village of Washington and the ten square miles of the District of Columbia might have accommodated two or three JPs but not forty-two. This was a patronage grab on the grand scale by a lame duck president and a dead duck political party. Madison and Jefferson agreed that twenty-six JPs were more than enough, thus eliminating sixteen. Four of the rejects petitioned the Supreme Court to issue a writ of mandamus against Secretary of State Madison to force him to commission one of the four, by name William Marbury.

Marshall issued an order to Madison, by name, to show cause why the writ should not be granted. On December 8 Jefferson sent his first message to Congress. (He did not personally accompany it, and for 112 years presidents did not appear in person to read their messages.) Jefferson spoke of Adams’s judiciary act and said there was insufficient business to warrant such an increase in courts and judges. Jefferson had an even more significant passage in his message which, had he retained it, might have changed the course of constitutional history: each Federal government department has the right to be its own judge, according to its own “judgments and uncontrolled by the opinion of any other departments.” Of the Sedition Law, he wrote, “I do declare that I hold that act to be in palpable and unqualified contradiction to the Constitution. Considering it then as a nullity, I have relieved from oppression under it those of my fellow citizens who were within reach of the functions confided to me.”

This passage was struck because Jefferson feared that “the public might be made to misunderstand” that any state or government branch was its own interpreter of the Constitution. Yet he himself saw no alternative but “the tyranny of the courts.” He was prematurely prescient. With hindsight, one now thinks it might have been best if the true war between the cousins had been out in the open earlier.

The Senate took up the matter first. That “elegant specimen” (New York Post) Gouverneur Morris himself appeared, doubtless still unaware of what an amount of work “his” Court would find to do once it had polished off the last of those Admiralty suits he regarded as their makework. But Breckinridge of Kentucky shifted the debate from any notion of judicial review to the less dangerous issue of a partisan creation of far more judges and courts than the country needed. On a party vote (Republicans sixteen, Federalists fifteen) Adams’s handiwork was voted down.

The House followed the Senate. The judiciary act was dead. On September 22 Marshall signed his contract to write the Life of Washington in five volumes; then he went, grumbling, on circuit. Jefferson was now busy with the Louisiana Purchase.

By chance, the members of the Supreme Court occupied the same boarding house near the Capitol, and Marbury v. Madison continued to engage their interest. Former Attorney General Lee represented Marbury before the Court. The justices came to a quick decision: they had already heard enough about the case in the congressional debates as well as in argument before them. Was Marbury entitled to his salary and the commission that went with it? Marshall said yes: Marbury was a justice of the peace as of the Senate’s ratification. Could he be withdrawn by the next president and Congress? If so, and should there be an argument over what was due to him as a matter of law, who interprets the law? The courts, said Marshall.

Question: how far could the courts go in interfering with the arrangements of the executive branch, particularly in the case of the Supreme Court, its equal? Foreign affairs, political actions were regarded as outside the Court’s domain, but where a law had been violated . . . Marshall liked to make analogies. Should a government officer, required by law to deliver land-patents to purchasers, not deliver a paid-for patent, what recourse did the purchaser have? The courts. What else? With that Marshall laid the foundation for judicial review. But now, practically speaking, he and the Court were helpless. If they should order Madison to give Marbury his commission, Jefferson would not only ignore the Court, as Jackson and Lincoln were later to do, but he might then introduce his—to Marshall, certainly—revolutionary limitation of the Court’s right to review the acts of the States and so on.

Marshall slipped out the back door; he acknowledged that the legitimately appointed Marbury ought to have redress but the writ of mandamus that his lawyer had demanded of Madison was, under Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789, “repugnant to the Constitution,” and void. The whole case must be thrown out of court as there was no applicable law violated.

Marshall was now a strict constructionist. Since the Constitution nowhere gave Congress the power to add or subtract from the Court’s original jurisdiction, the 1789 act had been dead on arrival. Thus Marshall settled Jefferson’s hash without the civil war which his heirs on the Court helped bring on—literally, by abstracting from Marbury v. Madisonthe principle of judicial review that then took a tragic turn when the Court declared unconstitutional (1857) the act of Congress known as the Missouri Compromise, barring slaves (like one Dred Scott) from “free” territory.

Finally, Marshall’s most ingenious chimera (Dartmouth College v. Woodward): “A corporation is an artificial being, invisible, intangible, and existing only in contemplation of law.” Marshall’s adjectives are compelling since they are usually applied, in this Godly republic, to God Himself if the word law is replaced by awe. This judgment is the cornerstone of modern Toryism.

Bernard Bailyn is always a good historian to consult in these matters. In his recent To Begin the World Anew, he concentrates on the formative years of the republic. In a short note on The Federalist and the Supreme Court he also examines just how many citations from The Federalist papers the Court has used, from Marshall to this day. In McCulloch v. Maryland, Marshall rejects a defense attorney’s citation from The Federalist with the cautionary—deflationary?—“No tribute can be paid to their worth, which exceeds their merit; but in applying their opinions to the cases which may arise in the progress of our government, a right to judge of their correctness must be retained.”

For most of the nineteenth century through the 1920s, the justices referred to the sacred tablets only occasionally. The most quoted were Hamilton No. 32, on exclusive and concurrent powers of taxation, and Madison No. 42, on powers delegated to the federal government. From the 1930s through the 1980s references increased. “Why the increase in citations?” Bailyn asks, “Why the papers’ increasing importance and sanctity?” Surprisingly, the so-called originalists on the Court, like Thomas and Scalia, seldom advert to them. Of the current Court, only the noble John Paul Stevens is most attentive to his predecessors. Bailyn makes the compelling case that the Court has not used—does not use—The Federalist as “a treatise on political theory or a masterwork on political science, but [as] a guide to the disposition of power in specific circumstances, an authority on the constitutional use of force and the constraints on the use of force in the intricate functioning of the federalist system of government in America.” Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. is smiling in limbo; William James nods agreement. Thomas Jefferson is currently negotiating a return, watering can in hand.

For those radicals who are always among us, it should be noted that we are not a nation “under God.” God is mentioned only twice in The Federalist, each time by James Madison, a clergyman’s son, who uses God as in the “only Heaven knows” sense. That is, if memory serves: in my old, now lost, copy of The Federalist God was mentioned twice in the index, while in the 1996 version he does not appear in the index at all. Political correctness? “Democracy” does get three references. The only useful one, as is so often the case, comes from Madison No. 10: “The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the delegation of the government; in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the greater number of citizens, and greater sphere of country over which the latter may be extended.” Did he suspect that his friend Jefferson would, in a dozen years, buy Louisiana? But Madison’s good sense deserts him as we, the wiser in future time, now know when he expatiates on the virtues of a large over a small republic as Montesquieu preferred. Madison opts for the large because: “it will be more difficult for unworthy candidates to practice with success the vicious arts by which elections are too often carried . . .” Well, as Joe E. Brown observed, no one is perfect. Meanwhile, let us hope that instead of a homely watering can, Jefferson Redux does not return with a guillotine.

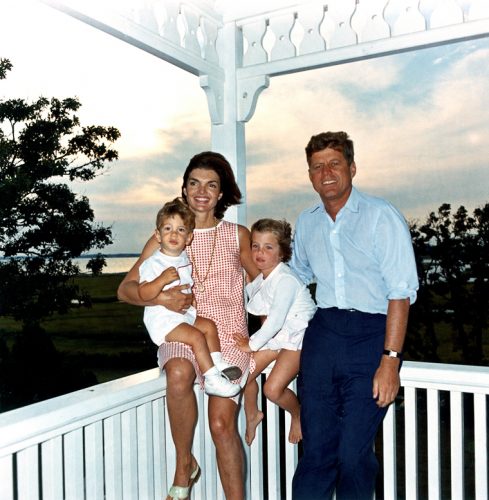

August 4, 1962: President Kennedy and family, Hyannis Port. Photograph by Cecil Stoughton, White House, in the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston.

One bright morning in 1961 at Hyannis beside the cold sea, after a vigorous game of backgammon, which I won, John F. Kennedy sat back, lit a cigar in the respite before his brother Bobby’s arrival from his house within the Kennedy compound.

“Your uncle Lefty Lewis . . . ” Jack began.

“Not my uncle. . .”

“But he’s Jackie’s uncle . . .”

“He’s not her uncle either. He was married to our stepfather’s sister, where he got the money to collect Walpole.”

“Merrywood!” Jack bit his cigar at the thought of that Virginia house from which emerged Jackie and I and a thundering herd, including a myriad of outriders none of us could ever keep straight. Jack liked to call us “the little foxes.”

“Anyway,” he went on, “somebody’s uncle, Wilmarth Lewis, spent his life collecting Horace Walpole, said to me, the other day, about the eighteenth century, his specialty, that, uh, how do you explain how a sort of backwoods country like this, with only three million people, could have produced the three great geniuses of the eighteenth century—Franklin, Jefferson, and Hamilton?”

“Time. They had more of it,” I said. “They stayed home on the farm in winter. They read. Wrote letters. Apparently, thought, something no longer done—in public life.”

Jack’s mind skipped about. “You know in this, uh, job . . . I get to meet everybody—all these great movers and shakers and the thing I’m most struck by the lot of them is how second-rate they are. Then you read all those debates over the Constitution . . . nothing like that now. Nothing.” It would be nice if he or I had come to a conclusion that morning but we did not. I did note, like John Adams, that our Constitution and laws were deeply grounded in England: “Anglo-Saxon attitudes,” I said.

Jack grunted. Although something of an anglophile, he was still an Irish Catholic. “Maybe it was something in the water,” he said helpfully. “I wish we had more of it, the water, that is.” Then Bobby arrived, on cue. (The Berlin Wall was going up.) I went for a walk on the beach, mildly aware that I was intersecting with history, which has its own tidelike rhythms, unknown to us at the time; and forever after too. Certainly, the inventors of our nation would be astonished at what we have done to their handiwork, their reputations as well.

Ten days before Jefferson died, he wrote some notes for the approaching fiftieth anniversary of his Declaration of Independence. “May it be to the world what I believe it will be . . . the signal of arousing men to burst the chains under which monkish ignorance and superstition had persuaded them to bind themselves, and to assume the blessings and security of self-government. . . . The general spread of the light of science has already laid open to every view the palpable truth that the mass of mankind has not been born with saddles on their backs, nor a favored few booted and spurred, ready to ride them legitimately, by the grace of God . . .” Science! To us that means total surveillance, electronic devices to track others, weapons of mass . . .

On July 4, 1826, Jefferson died. For posterity he wanted to be known as the author “of the Declaration of American Independence, the statute of Virginia for religious freedom, and father of the University of Virginia.”

A few hours later, the dying John Adams said, “Thomas Jefferson still lives.” But Jefferson had already departed. John Adams had his epitaph ready; it was to the point: “Here lies John Adams, who took upon himself the responsibility of the peace with France in the year 1800.”

“Let us now praise famous men and our fathers that begat us,” as the New England hymn of my youth, based on Ecclesiacticus, most pointedly instructed us. Meanwhile, dear Jack, in the forty years since your murder, I have pondered your question, and this volume is my hardly definitive answer.

From Inventing a Nation: Washington, Adams, Jefferson by Gore Vidal; published by Yale University Press in 2004. Reproduced by permission.

Gore Vidal, novelist, essayist, and playwright, was one of America’s great men of letters. Among his many books are United States: Essays 1951-1991 (winner of the National Book Award), Burr: A Novel, Lincoln, and the recent Perpetual War for Perpetual Peace.

Further Reading

Featured Image: “WFB debating Gore Vidal, 1968” by Levan Ramishvili, licensed for use on the public domain via flickr.