Baptism

Peter Marshall—

Imitation of Christ began with becoming a Christian. That was the easy part. It happened within days of being born, when a baby was baptized in the stone font usually found, in symbolic placement, near the entrance of the church. The ceremony involved a ritual cleansing with water, and the bestowal of a name, while an officiating priest invoked on the child the power of ‘the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit’, the three ‘persons’ of a single Trinitarian God.

Baptism could be an elaborate affair. A few days after his birth on 28 June 1491, Henry, second son of King Henry VII and his wife Elizabeth, was baptized in the church of the Observant Franciscan friars at Greenwich, on a specially constructed platform hung with richly embroidered cloths and canopies. The font was made of silver, and the priest was a leading clergyman of the realm, Bishop Richard Fox of Winchester. Yet, spiritually, the little prince did not get anything more out of it than a child of the lowliest of his father’s subjects. In a rite that was part exorcism, the curse of original sin was erased from the infant’s soul; he or she was literally ‘christened’. Mothers remained at home for six weeks after the birth of a child, and fathers generally stayed away from the ceremony. But the godparents, who made statements of faith on the baby’s behalf, would be huddled around the font. A contemporary describes them nervously asking the priest, ‘How say you . . . is this child christened enough? Hath it his full Christendom?’

There was always an element of anxiety in an age when so many infants failed to survive their first days and weeks. Babies dying unbaptized were not Christians, could not be saved. Logically, this implied the eternal torments of hell. But, long before 1500, the idea gained near- universal acceptance that their souls went not to hell but to a neighbouring ‘limbo’ (from the Latin for fringe or boundary) – a place without vision of God but equally without pain. Another limbo housed ‘good pagans’ who lived and died before the incarnation of Christ. In an emergency, not just a priest, but anyone – even a female midwife – could validly baptize a child. All this suggests how, over time, the rigid rules of the Church might soften, in response to theological reflection, or the demands of simple humanity; there was flexibility in the system, and a dose of perplexing untidiness.

Baptism illuminates some other core assumptions of Christianity, as it was lived and taught across western Europe in the later Middle Ages. The faith was inclusive, and all-embracing. With the exception of a small number of Jews and a still smaller number of Muslims, no one ‘chose’ to be a Christian. Membership of the Church, and formal profession of Christian faith was simply coterminous with human community. This makes it profoundly unhelpful to speak, as historians still tend to do, about ‘religion and society’, as it is impossible to identify where the one stopped and the other began.

Perhaps it is even unhelpful to speak about ‘religion’ at all, in the modern sense of a contained sphere of thought and activity, separable from other aspects of experience. Early sixteenth- century people did use the word ‘religion’, but they nearly always meant by it the specialized ritual practices undertaken in monasteries. When it came to ordinary ‘lay’ folk, people might praise their faith, piety or devotion – words signifying an intensified presence of universally valued ideals and beliefs that underpinned all social and political order. There were certainly people, perhaps significant numbers of people, who were ‘irreligious’, in the sense of not taking seriously enough the moral demands of their Christian faith. Baptism removed ‘original sin’, but it did not remove the propensity to sinful behaviour that was the common lot and legacy of humankind. Others did not believe precisely what they were supposed to believe, and became stigmatized as ‘heretics’.

But it is unlikely that late medieval England contained ‘atheists’ in anything akin to our modern understanding of the term. God’s presence was ubiquitous, and if winning his favour was not always at the forefront of people’s minds, his judgment on them was the inescapable backdrop to their lives. Baptism also illustrates the means through which God’s presence was sought and experienced. It was a sacrament, one of seven such rituals, which, by the late Middle Ages, the Church had designated with this title. The others were confirmation, marriage, ordination, anointing of the sick (extreme unction), penance (confession) and the Eucharist. Sacraments were symbols and more than symbols. They actually effected what they signified: the washing away of sins, in the case of baptism. In the technical jargon of the Church, a sacrament comprised ‘matter’ and ‘form’. The matter was some raw material or point of departure – water, oil for anointing, bread and wine for the eucharist, sorrow for sins, mutual consent, and subsequent consummation, in marriage. The form was a recital of prescribed words. Together they guaranteed God’s life-giving favour to the recipient; they produced the presence of ‘grace’

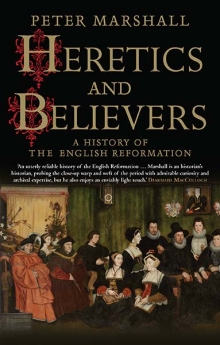

From Heretics and Believers by Peter Marshall. Published by Yale University Press in 2018. Reproduced with permission.

Further Reading