Q&A with Denise Murrell, author of Posing Modernity

Yale University Press: Posing Modernity began as a term paper that became a dissertation and has now become both an exhibition and a book. What changes or shifts in focus have you encountered since you started the project?

Denise Murrell: The main change was to shape the initially academic project into a  narrative with a story line that would have the widest possible appeal. I want to get not just art-knowledgeable audiences to come see the show, I want everybody to come see the show! Amy Canonico, my editor at Yale University Press, was very helpful. She read my dissertation and identified some of the most theoretical arguments. For example, the construction of vision: how it is that people can be conditioned to not see, or not pay attention to, something that is right there before them. There’s a rhetorical discussion around this idea that, she pointed out, would likely not be of widespread interest. She characterized the goal of the book as a discussion of the artworks themselves, a clear explanation of what I see in them, and a guide toward helping readers to look closely at these works as well: letting the works speak for the arguments I was trying to make. The exhibition opens with a look at Édouard Manet’s three portrayals of the black model Laure over the course of one year. In one of these portraits, she posed as the black maid in his very famous painting Olympia. I wanted the audience, and the reader of the book, to look at that work, and to compare it to other images from the period, and see what was modern about that portrayal of Laure. These types of juxtapositions help to establish a way of thinking about art history that I hope will be really compelling to people.

narrative with a story line that would have the widest possible appeal. I want to get not just art-knowledgeable audiences to come see the show, I want everybody to come see the show! Amy Canonico, my editor at Yale University Press, was very helpful. She read my dissertation and identified some of the most theoretical arguments. For example, the construction of vision: how it is that people can be conditioned to not see, or not pay attention to, something that is right there before them. There’s a rhetorical discussion around this idea that, she pointed out, would likely not be of widespread interest. She characterized the goal of the book as a discussion of the artworks themselves, a clear explanation of what I see in them, and a guide toward helping readers to look closely at these works as well: letting the works speak for the arguments I was trying to make. The exhibition opens with a look at Édouard Manet’s three portrayals of the black model Laure over the course of one year. In one of these portraits, she posed as the black maid in his very famous painting Olympia. I wanted the audience, and the reader of the book, to look at that work, and to compare it to other images from the period, and see what was modern about that portrayal of Laure. These types of juxtapositions help to establish a way of thinking about art history that I hope will be really compelling to people.

YUP: Did making any of these changes wind up affecting how you thought about any of your overarching arguments, or was it more a matter of streamlining the material for a general audience?

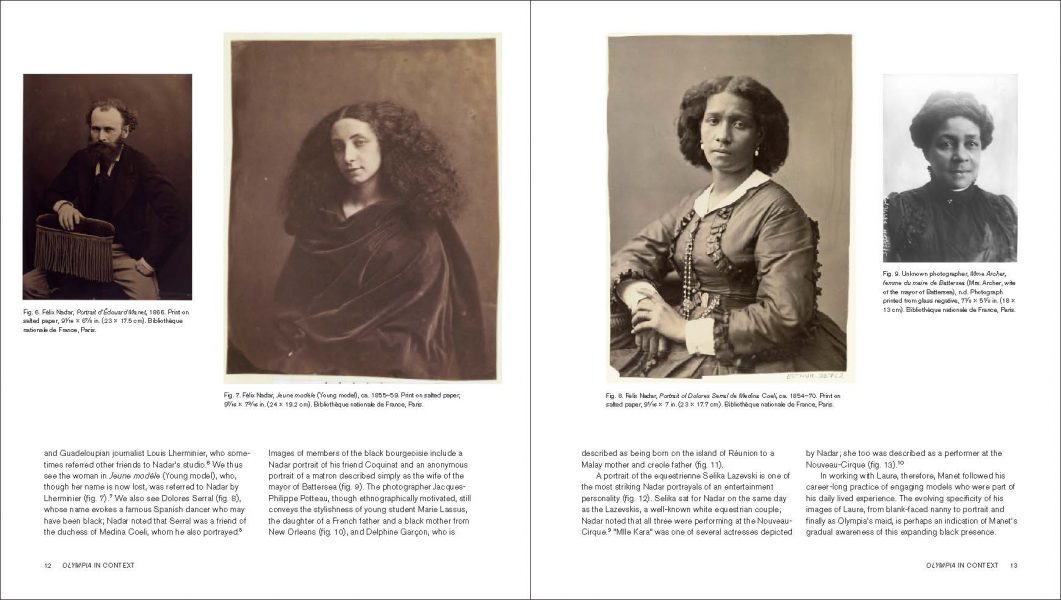

DM: I think the changes we made for the exhibition and the book were all based on arguments that were already there, but the process did sharpen the arguments for me. The book begins with images of Laure in Olympia, alongside several pages of photographs of black Parisians who lived and worked in the same neighborhood as Manet and the Impressionists. I wanted to make clear that Laure wasn’t an imagined figure. She’s a representation of the racial reality of 1860s Paris, some fifteen years after the French abolition of territorial enslavement in 1848. I wanted to show that she is occupying one of several social roles that free black Parisians occupied at this particular moment, when Manet and the Impressionists were working. Many of the photographs were taken by the photographer Félix Nadar, who was a friend of Manet and who also made iconic portraits of Manet and the famous writers and artists in his circle. The fact that there were any number of black Parisians coming through Nadar’s studio, which we were able to show through these photographic spreads, helped sharpen the argument I was trying to make about the painting.

YUP: What kinds of difficulties did you face in putting together this exhibition?

DM: I think I faced the same issues that any emerging curator would – this is my first exhibition. I finished my dissertation in 2013, and had immediate interest from the Wallach Art Gallery in the possibility of staging it as an exhibition. My work was especially relevant at that moment, because they were in the process of opening new galleries on 125th St., the main thoroughfare of Harlem, and they liked the idea of dealing with iconic artists like Manet and Henri Matisse in the context of a multiracial exchange – one that I suggest was key to the foundation of modern art. The interest was there, but we lacked funding, and that was a challenge. An unknown curator with an unconventional way of looking at some very well-known artists (Manet, Matisse, the Harlem modernists) that people think they already know everything about) was a combination that made it difficult to find funding initially. We were over a year into the process of looking for funding when we were able to present the project to Darren Walker at the Ford Foundation. Fortunately, he stepped up right away and offered to underwrite the initial years of research and development, which made this whole thing possible. In the end, adversity led us to what was, in hindsight, a great way for me personally to do the exhibition. If a major museum had taken it on, I might have wound up assisting a senior curator. As it turned out, I was able to keep it as my project, seeking advice from experienced curators, who were extremely helpful, but I had the final word about the way it looks on the walls of the gallery. That’s a real privilege for a first-time curator. I had an analogous experience with the layout of the book, working closely with Amy, and having significant influence over the design and layout, the placement of the images within the text. I worked with incredibly creative and skilled professionals and learned a lot from them. Seeing the images in the book for the first time was an emotional experience for me. No Ph.D. student has the means to pay for all of the permissions fees to include the images together with the text in their dissertation. So I’d never seen, except in my mind’s eye, the text and the more than 175 images all together until the book came together, and it was a deeply gratifying experience to see that.

YUP: In the Hyperallergic piece about the exhibition, David Carrier wrote, “visual art taken by itself generally offers a relatively thin record of cultural history.” How do you treat the presentation of supplemental historical research and context in an exhibition and book like Posing Modernity?

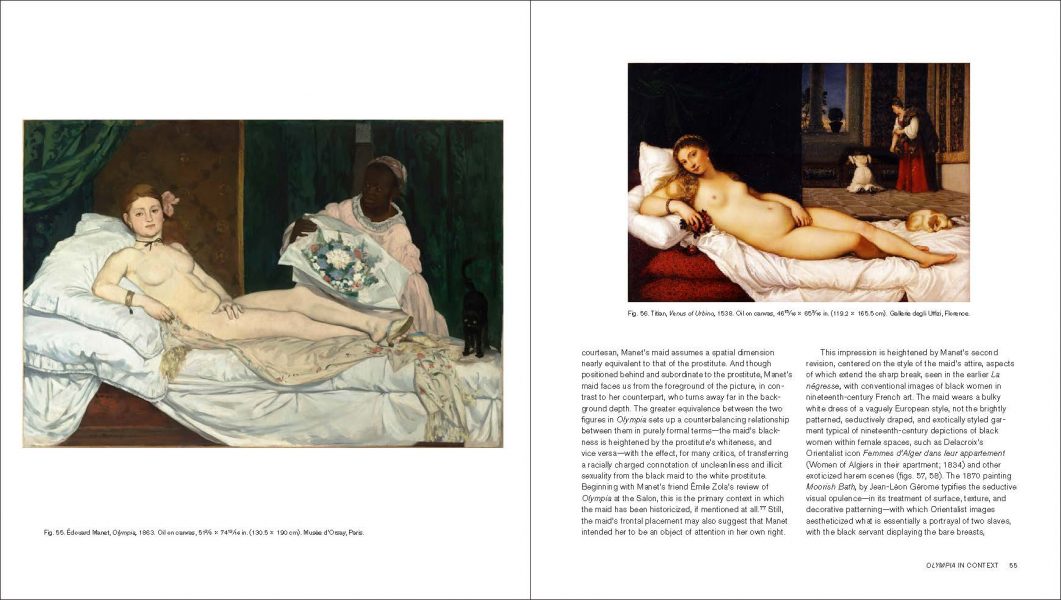

DM: There is an ongoing argument about whether art historians should focus exclusively on looking at the actual works of art, that is, what’s there in front of them, as the main source, if not the only source, of information about that work of art. I think that you do want to encourage everyone to focus on the artwork, but some level of context beyond the image itself can definitely enrich the viewing experience. You may see things that raise questions for you about the range of possible interpretations. The more you know about the socio-historical context, the more you are able to imagine a variety of interpretations and conclusions. As a student, I started with formal analysis when I first looked at Olympia. I saw that this maid figure was present in the painting, and I compared it to the precedent images for Olympia, mainly Titian’s Venus of Urbino. In that Venetian Renaissance painting, the maid figure is clearly in the background; she’s turned away, and not part of the drama playing out at the forefront of the painting. The exact opposite is true of the black maid figure in Olympia.

Just through formal analysis, you can conclude, “Manet is presenting this painting as being about both of these women.” What can we know about what these two women represent? All of the classes I’ve attended, and all of the literature I’ve read about the reclining nude prostitute in this painting, highlight the class and gender issues of a modernizing Paris and the increasingly public role of sex work. But in this painting, the maid is right there at the front of the painting, too; she takes up almost the same pictorial space as the prostitute, and she seems even to be in some kind of discussion with the prostitute. I think it becomes relevant to consider that this is potentially a representation of the changing racial reality in Paris in the first fifteen years after the French abolition of territorial slavery. Widening the scope from there, and looking at other portrayals of black women that are available to us from that period, you do see other social roles represented. You see Laure herself portrayed as a nanny and in Manet’s portrait of her, she could be one of many things – she’s a young woman in a fashionable French neckline, she could be a waitress in a café, she could be a shopgirl, she could be a paid artist model (which we know for sure she was), among other possible roles. Looking at the work can make you curious to understand the context in which the painting was made. And an understanding of the context leads, in my view, to a richer interpretation of the work itself.

YUP: Do you think that your representation of Olympia will be integrated into art history education?

DM: I hope so! The first group tour I did at Columbia was for over 20 instructors of the Art Humanities course at Columbia – which is a look at masterpieces across the ages of Western art history in a way that attempts to train viewers to understand what they’re looking at and to think about the ways that images can be contextualized. These instructors then brought their own classes through the show, and I had a number of discussions afterward with both the instructors and the students. There is a very welcome effort underway, at Columbia and elsewhere, to broaden the idea of the canon, to introduce diverse new perspectives to the history of Western art, and I hope Posing Modernity helps with that. I sense that there is a growing feeling that it would be old-fashioned now to conduct a discussion of Olympia and only talk about the prostitute, without saying anything about the maid figure. We have more information, and we can use it to generate interpretations of both figures.

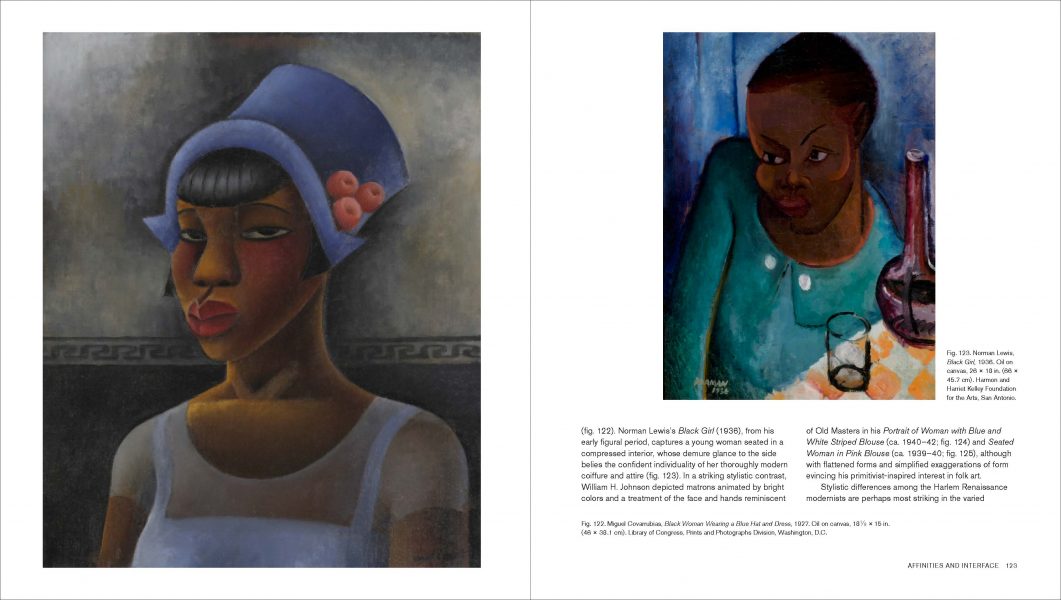

Over successive generations of artists, you see this pictorial style reinterpreted. The Harlem Renaissance modernists of the early 20th century often studied in France, after which they attempted to portray the new, urbane life of American cities in the midst of the Great Migration, when 6 million African Americans moved from the rural south to New York and Chicago, etc.

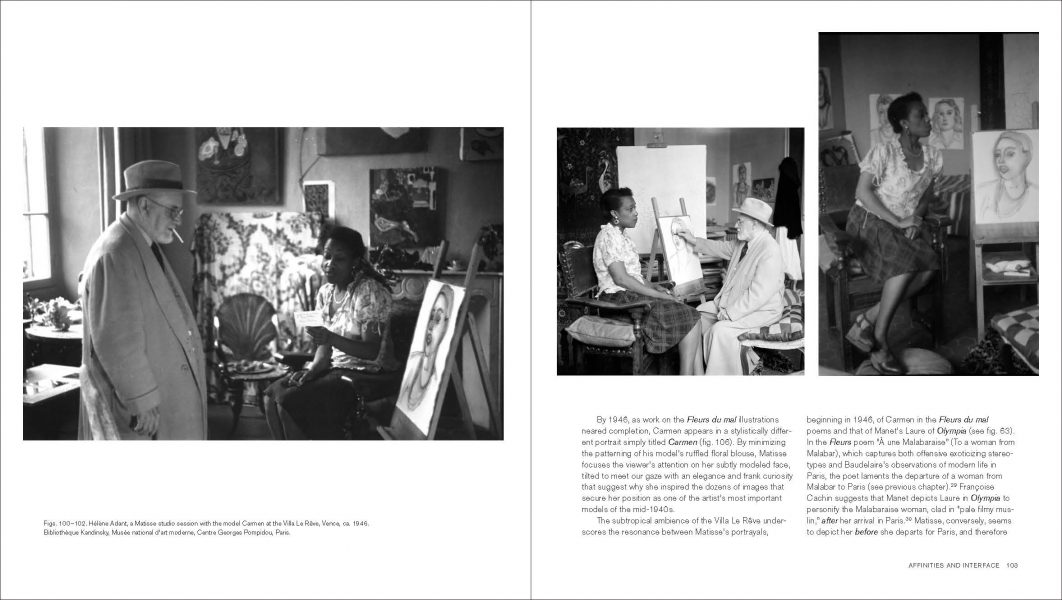

Matisse came to the U.S. in the 1930s and engaged with some of these artists and musicians, and you see a certain affinity in his work when he, a decade later, worked with black models and presented them in terms of a modern, mid-20th century style as opposed to a backward-looking 19th century style.

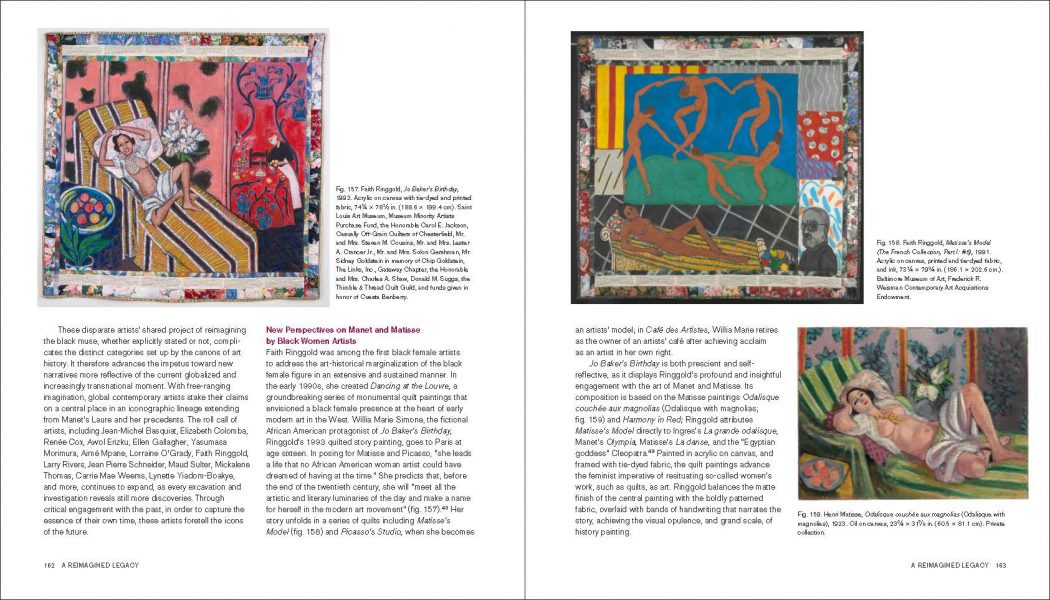

At the end of the show and the book, there are works by contemporary artists, many of them living artists, of diverse nationalities and artistic styles, who are still reimagining Olympia, reimagining a portrait of Laure, working with the imagery of Manet, Matisse, Romare Bearden and the Harlem modernists to figure out a style they might use to make art that is fully of our present moment.

YUP: What are working on for the future? What do you hope for the future of this exhibition?

DM: My most immediate future project is that the Posing Modernity exhibition will travel to the Musée d’Orsay in Paris. The Musée d’Orsay show will be expanded to over twice the size of the New York show and it will cover a wider historical period. In its current incarnation, the show starts with 1860s Paris – Manet and the Impressionists. The Musée d’Orsay, titled The Black Model from Gériault to Matisse, will cover the era from 1801—1848, that very fraught period in French history and in art history, during the final fifty years of French territorial enslavement. There will be some very challenging works there that I think will be educational for all of us to see. I am a co-curator of the Musée d’Orsay show, and so I will go to Paris and be based there for a time. I’ve had a wonderful invitation from Columbia-Paris to teach an undergraduate seminar there, based on the exhibition. Part of the course will be taught at the galleries of the Black Model exhibition in the Musée d’Orsay. This will take me through the end of next summer, and I’m really delighted to have the opportunity. I am definitely beginning to think about what the longer-term future will be, but I intend to fully enjoy that time in Paris!

Denise Murrell is the curator of the Posing Modernity exhibition and Ford Foundation Postdoctoral Research Scholar at the Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery at Columbia University.