A Personal Canon: Stephen Houston on Five Influential Texts

Books can amuse, provoke, and uplift. The best ones are also, just a bit, like CRISPR technology. That breakthrough allows biochemists to edit genomes. Potent, lasting books reedit our minds.

For me, CRISPR works are not the writings that made a difference to Western art historians. Richard Stone and John-Paul Stonard have collected such evaluations in The Books that Shaped Art History (2013), a learned, sympathetic, at times tart set of essays. Why do I worry about Great Books in visual culture? Because such lists change, often at a rapid clip. Modish topics or authors yield to new fashions, and I’ve never liked being told what to read or cite, or having to mind the hierarchies of importance established by others. There is also that old complaint: favored books privilege Western art and its distinguished champions of the moment. Images and objects from the West are the default, along with the assumptions of those who study them. What would Paul Cézanne or Clement Greenberg think of Maya artworks, if they had bothered to look at them? For me, the question carries little to no interest. Let there be no mistake, however. There was some appropriation, if one-sided. For his ceramics, Picasso stole from Moche stirrup pot designs in early Peru, and Henry Moore lifted shapes from recumbent “Chacmool” sculptures in Yucatan. (Of course, appropriation and cross-fertilization with the West operate strongly in colonial and post-colonial times.)

Books that mattered to me are more idiosyncratic. I am not a conventional historian of art. Instead, I visit from, and return to, anthropological archaeology. My day job, other than as a teacher or administrator, is to run digs or advise them, to analyze observations from lidar (laser-emitting) devices flown in planes, to translate ancient Maya texts and decode their glyphic signs, and to relate carving, building, painting, and city plans to models of how people think. I pay attention to comparable societies and abstract formulations of human inequality, hence an early infatuation with Max Weber’s collected works (1988). But I do esteem the subtle thought and prose of art historians. They think hard about what it means for humans to show and see.

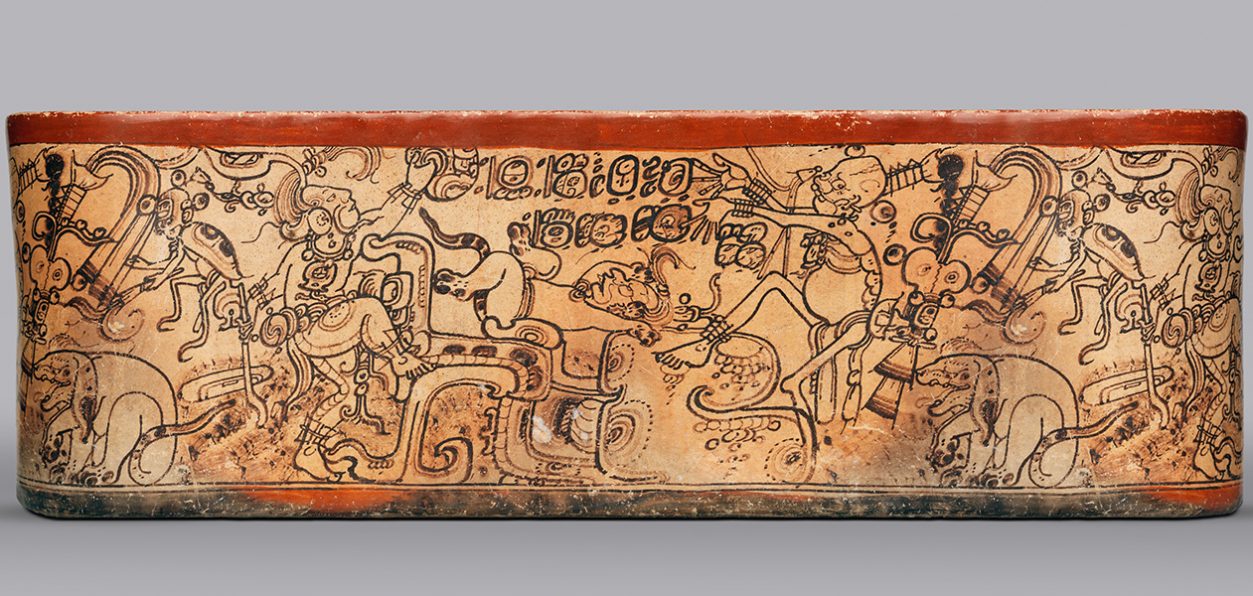

Michael Coe, The Maya Scribe and His World (1973)

In order of influence, my CRISPR list starts with Michael Coe’s The Maya Scribe and His World. It is an elegant, witty, and erudite book. Printed by the Meriden Gravure Company on high-weight paper (most copies I know have broken spines), its inspiration was a costly folio prepared some 50 years before by the University Museum of the University of Pennsylvania. Within its pages are shots by Justin Kerr, on the verge of becoming the premier photographer of Maya art. Stippled rollout drawings by Diane Griffiths Peck look as though inked by hypodermic needle, so fine is their quality. Maya Scribe proved that imagery on ceramics, ignored to strange extent by other specialists, offered the richest imaginable data. There were scenes of kings, courtiers, and gods, along with meltingly beautiful examples of the “lost” calligraphy of the Maya—no books survive from the height of its civilization. How could anybody resist? I did not, although still an undergraduate.

James Deetz, In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life (1977)

About this time, I fell under the sway of another book, well outside my field. This was James Deetz’s In Small Things Forgotten. I did not know I would end up at the institution, Brown University, that sponsored Deetz’s digs in colonial New England for a decade or so. In fact, his portraits still lurk in the annual photographs posted in my department. (Sadly so, for most students have little idea who he was or care that he roamed our halls.) Small Things was, in fact, about large things that are neither forgettable nor forgotten. It revealed how archaeologists can tell gripping, persuasive stories about people through the artifacts, building interiors, pots and other unpromising debris left behind from early America. Deetz was also a good friend of Henry Glassie, the great folklorist and historian of vernacular buildings, by chance a memorable undergraduate teacher of mine. Through collaboration, I learned, scholars could bundle expertise and talent. They could revivify, by skill and imagination, the fervors of the past. The pen-and-ink drawings in Small Things encapsulated its charm. I yearned to write with at least some of that power.

Alfredo López Austin, Cuerpo humano e ideología: Las concepciones de los antiguos Nahuas (1980 [1988])

Another dazzling book was Alfredo López Austin’s Cuerpo humano e ideología. Maya Scribe shimmered with promise, a door coaxing, even insisting, that we enter. Cuerpo humano was a fully realized volume that mapped out what the Aztecs thought about the human body and why we should care. Here was the kernel of Aztec existence, the frame of sentient life and the spirits or energies flashing within. Cartography requires that each signpost, road or byway be recorded. That is what López Austin did to compelling, exhaustive degree. With colleagues, I plundered his example in The Memory of Bones, a volume about ancient Maya concepts of the body (2006).

Duc de Saint-Simon, Memoirs of Duc de Saint-Simon, 1691-1709: Presented to the King; translated by Lucy Norton (1999-2000)

The final two books are, first, the abridged volumes of the Duc de Saint-Simon’s memoirs about that glittering snake pit, the Versailles of Louis XIV and the regency of Saint-Simon’s ally, Philip II, the Duc d’Orléans (1999–2000, a re-issue). Mordant, petty, at once arrogant and obsequious, the Duc must have been the most incisive observer ever, anywhere, of a royal court. He saw them less as places of idle pleasure than danger and opportunity, patronage and spectacle. I have never viewed a Maya court in the same way again. (John Adamson’s edited book, The Princely Courts of Europe, 1500–1750 [1999], had an equal influence.)

Alfred Gell, Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory (1988)

Finally, not the easiest read, is Alfred Gell’s Art and Agency, published after the death of its author. A figure of paradox, Gell was strongly attracted to art, especially Titian, Duchamp, and Polynesian tattoos, yet he suffered from poor eyesight for much of his life. A myopic drawn to looking. Allured by imagery, said to be a gifted draftsman, Gell preferred to dissect it in cold, analytical fashion. Yet he loved also to break boundaries, to read whatever he wanted, to think in sustained ways about how art operates: expressive works needed anthropology, anthropology could be enriched by closer attention to art. From Art and Agency came something new and integrative.

At their most active, CRISPR books do that for each of us.

Stephen Houston is Dupee Professor of Social Science and chair of the Department of Anthropology at Brown University. A Yale University Press author, he has published The Life Within: Classic Maya and the Matter of Permanence (2014) and The Gifted Passage: Young Men in Classic Maya Art and Text (2018). In 2011, Houston, the recipient of a MacArthur Fellowship, was also awarded Guatemala’s highest honor, the Order of the Quetzal in the grade of Grand Cross.

Bibliography

Adamson, John, ed. The Princely Courts of Europe, 1500–1750. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1999.

Coe, Michael D. The Maya Scribe and His World. New York: Grolier Club, 1973.

Deetz, James. In Small Things Forgotten: The Archaeology of Early American Life. New York: Anchor/Doubleday, 1977.

Gell, Alfred. Art and Agency: An Anthropological Theory. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1998.

Houston, Stephen, David Stuart, and Karl Taube. The Memory of Bones: Body, Being, and Experience among the Classic Maya. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2006.

López Austin, Alfredo. Cuerpo humano e idelogía: Las concepciones de los antiugos nahuas. 2 vols. Mexico City: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, 1980.

López Austin, Alfredo. The Human body and Ideology: Concepts of the Ancient Nahuas, trans. Thelma Ortiz de Montellano and Bernard Ortiz de Montellano. 2 vols. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1988.

Saint-Simon, Duc de. Duc de Saint-Simon: Memoirs, ed. and trans. Lucy Norton. 3 vols. London: Prion, 1999–2000 (a re-issue).

Stone, Richard, and John-Paul Stonard. The Books that Shaped Art History: From Gombrich and Greenberg to Alpers and Krauss. London: Thames & Hudson, 2013.

Weber, Max. Economy and Society, ed. Guenter Roth and Claus Wittich. 2 vols. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988.