Sparta and Athens: From Peace to War

Paul A. Rahe—

In his now neglected masterpiece Marlborough: His Life and Times, Winston Churchill once hazarded the following observation:

Battles are the principal milestones in secular history. Modern opinion resents this uninspiring truth, and historians often treat the decisions in the field as incidents in the dramas of politics and diplomacy. But great battles, won or lost, change the entire course of events, create new standards of values, new moods, new atmospheres, in armies and in nations, to which all must conform.

Though written with an eye to the duke of Marlborough’s great victory in the battle of Oudenarde, Churchill’s claim applies with no less and perhaps even greater force to the Battle of Plataea in 479 BC.

Prior to Sparta’s defeat of the Persian army captained by Mardonius on that occasion, there was every reason to suppose that the Greek resistance would collapse and that Hellas would soon fall under the sway of the Great King. When the dust had settled, however, it gradually dawned on all concerned that affairs had undergone a decisive change; and everyone in and on the periphery of the Mediterranean world began to reassess.

The empire ruled by the Great King Darius and his son Xerxes commanded a greater proportion of the world’s population and of the world’s resources than any dominion that preceded or followed it, and it dwarfed in size and population all conceivable rivals. The ancient world was lightly populated. The only regions of any size in which population density was considerable were the four great river valleys where irrigation made possible the production of grain or rice on a very grand scale. In the early fifth century, only one of these four – the Yellow River in China – lay outside Darius’ and Xerxes’ control. Over the fertile and well-watered valleys of the Indus, the Nile, and the Tigris and Euphrates and the great civilizations to which they had given rise, the first two Achaemenid monarchs held sway. And Xerxes marshalled the resources that this great empire afforded him against the coalition of diminutive Greek cities that rallied behind Lacedaemon—or Sparta as it is known today—in 481, 480, and 479.

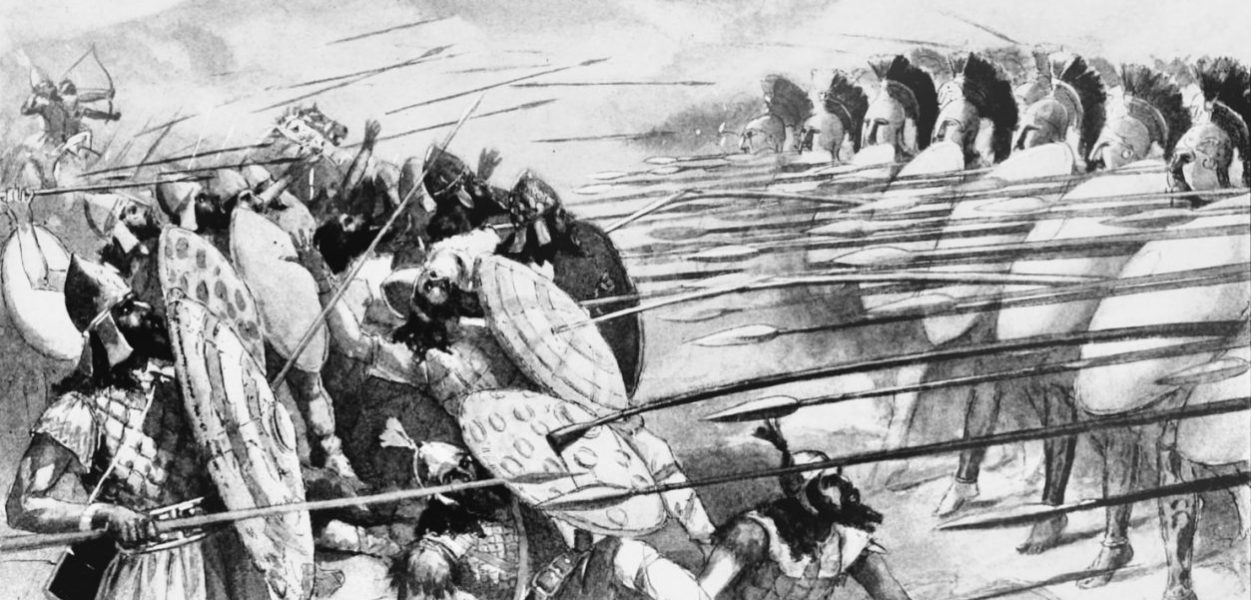

This, however, he did in vain. For the Greeks outfoxed him in 480, when Themistocles of Athens lured the Great King’s fleet into the narrows separating the island of Salamis from Attica—where, due to their numbers, the Persian triremes were apt to run afoul of one another, and the much smaller, much less maneuverable Hellenic fleet could in familiar waters operate to best advantage. There the Greek triremes wreaked such havoc on the Achaemenid force that it was left numerically and morally incapable of launching a second attack. They did the same in 479 to Mardonius, the commander Xerxes had left behind. Pausanias of Lacedaemon feigned a loss of nerve and staged an awkward, apparently desperate and disordered withdrawal from the southern bank of the Asopus River in Boeotia and lured Mardonius and the Persian infantry across that river onto terrain in the foothills of Mount Cithaeron where, he had good reason to believe, the Persian cavalry could not operate. There the badly outnumbered hoplites of Sparta and Tegea then formed up in a phalanx, shoved their way through the wall of wicker shields set up by the enemy, and relentlessly slaughtered without remorse the handful of dedicated spearmen bearing small shields and the multitude of shieldless archers doubling as spearmen whom Mardonius had deployed against them. That a ragtag navy and militia, supplied by tiny communities hitherto best known for their mutual hostility, should annihilate an armada greater than any the world had ever known was then—and remains today—both a wonder and an occasion for rumination.

Was the war really over? Or would the Persians soon return? Was this victory an accident or an indication of a hitherto unsuspected strategic superiority on the part of the Hellenes? And if the war really was over, what was to come next? What in particular were the Greeks—and their Spartan leaders—going to do with this remarkable victory? Would they carry the war to Asia? Would they free from the Persian yoke the islanders of the eastern Aegean, the Greeks of Thrace and Asia Minor, as well as those of Cyprus? Or would they be satisfied with defending the Balkan peninsula and the nearby islands from Achaemenid domination?

These were the questions asked, and there were more—for the unity that the Hellenes had displayed to good effect in this war was unprecedented. Would they maintain the solidarity that they had achieved in 480 and 479? Or would they return to the petty squabbling among themselves that had occupied them in the past? Would the Spartans try to turn their hegemony into an empire? And what about the Athenians, who had supplied nearly half of the Greek fleet and had demonstrated such remarkable prowess at Salamis?

These were among the concerns that preoccupied the handful of Greeks blessed with strategic vision and a broad, panoramic view—and none were more perplexing than those pertaining to Hellas proper. After all, wartime coalitions are fragile. Sentiment may well play a role in holding alliances together. But it is generally fear that occasions their formation and provides the requisite cement—and when, after a great victory, that fear gradually dissipates, as it will, coalitions tend slowly to dissolve and other antagonisms then emerge anew . . . or reappear.

Each of the thirty-one cities participant in the victorious coalition had her own agenda; each had her own history and her own concerns. The same can be said for the communities which had remained aloof—and also for those which had sided with the Persians. Moreover, most of the Greeks who lived in these diverse cities and were possessed of a voice in the public assemblies that governed these tiny republics were not just parochial in their outlook. They were also profoundly confused, as well they might be. For they were on the threshold of an uncharted new world. The outcome of the contests at Plataea and Mycale had decisively altered not only the course of events. It had also opened up new vistas, and it had fired imaginations. In the process, it really had forged new standards of values, new moods, new atmospheres, in armies, in navies, and in cities, to which all in the foreseeable future would have to conform.

It took the Hellenes well over a decade to sort out the implications of their achievement. Everyone soon recognized that for logistical reasons the Persians could not return absent a recovery of their dominance at sea. Initially, the Spartans, who had at the outset been accorded command on both land and sea, reluctantly assumed responsibility for preventing such an eventuality. In time, however, with a mixture of resentment and relief, they ceded the task to the Athenians, who were much better-equipped with triremes and eager to take it on. As long as the Persian threat seemed real, the Lacedaemonians were content with this arrangement. Whenever, however, it appeared that the Athenians had succeeded magnificently in this enterprise and it looked as if, in the Aegean, Achaemenid Persia was a spent force, the Spartans became alarmed, fearing that the growth in Athenian power that had made this victory possible had rendered Athens a threat to the alliance system within the Peloponnesus that they had long before forged with an eye to providing for the defense of their regime and the attendant way of life.

The process by which the Hellenic League collapsed, the enduring strategic rivalry between Sparta and Athens that then emerged, and the wars that this rivalry occasioned are of intrinsic interest. But, as Thucydides insists, they are also of interest as a template for understanding what is apt to happen within a bipolar world under similar circumstances. In late February 1947, this led George C. Marshall to express to a university audience grave doubts as to “whether a man can think with full wisdom and with deep convictions regarding certain of the basic international issues today who has not at least reviewed in his mind the period of the Peloponnesian War and the Fall of Athens.” Marshall had in mind the tensions between the United States and the Soviet Union that were then giving rise to the Cold War. It is not fortuitous that, with an eye to China’s emergence as a great power, Graham Allison and others are directing our attention once again to the developments, charted by Thucydides, that long ago gave rise to an enduring strategic rivalry between the Lacedaemonians and the Athenians. We study the past for the purpose of informing the present.

Paul A. Rahe is a Rhodes Scholar and holds the Charles O. Lee and Louise K. Lee Chair in the Western Heritage at Hillsdale College. He is the author of numerous books including the three-volume Republics Ancient and Modern.

Further Reading: