Racial Passing in America

Adele Logan Alexander—

Over the years, the practice of “passing” for white has variously been considered wicked, cowardly, deceptive, essential, all or none of the above by much of the African American community. Certainly, it was and is controversial.

In years, decades, and centuries past, a number of light-skinned African Americans “passed,” either briefly, permanently, or situationally. Their stories are legion. This certainly has been the case for several members of my own family.

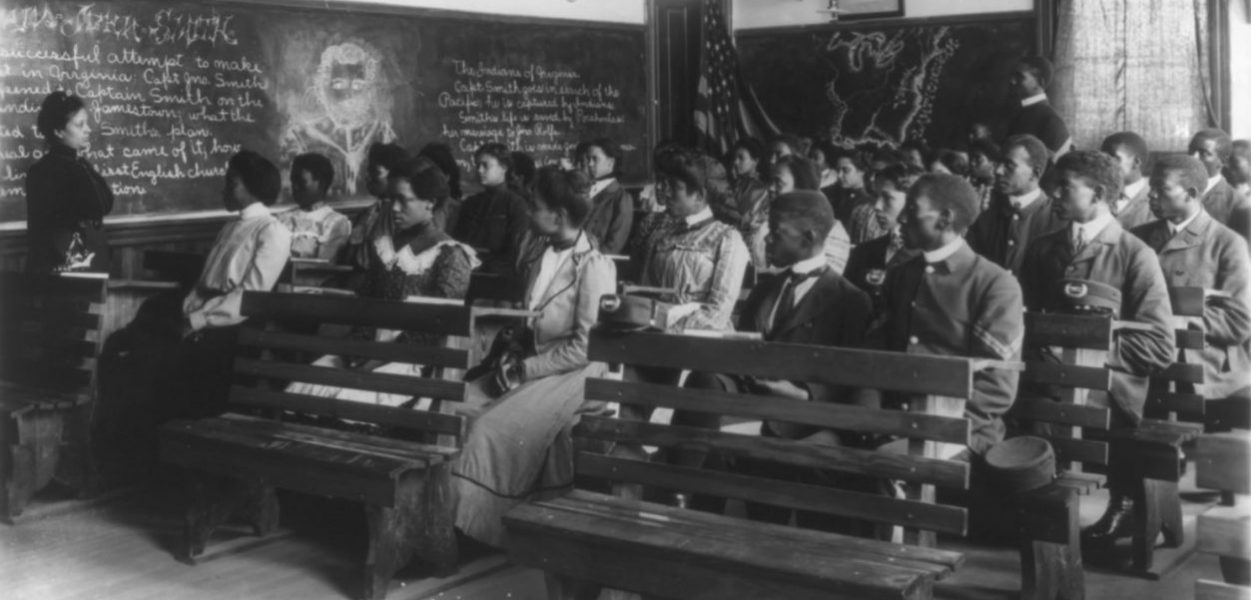

In the early 1900s my great uncle Tom Hunt (my relatives always laughed about having an Uncle Tom, especially one who passed for white) learned to love agronomy sitting at the feet of the great black scientist and teacher George Washington Carver at Tuskegee Institute, where he lived with his older sister and her family. Then Tom moved to Massachusetts, where he attended and graduated from the agricultural department of the state university. No one asked if he was “a Negro,” and thereafter, as far as I can ascertain, he apparently didn’t say that he either was or was not. Everyone simply assumed that he was white. The renowned University of California soon hired him to teach agronomy—but apparently, no one there even knew that they had a “colored” faculty member until the 1960s.

Much the same thing happened with my father’s brother Paul. After graduating from Pennsylvania’s Lincoln College (a first-rate, historically black school), he earned a master’s degree at Cornell and was recruited by the United States Forestry Service, which also didn’t know that it had a “black” employee for another thirty years. Paul moved to Oregon and was “lost” to the African American community thereafter.

My “colored” family sometimes disparaged or even laughed at those relatives for what they considered their “cowardice,” but accepted their actions as necessary.

I’ve wondered what those men’s lives must have been like. Did they awaken every morning worrying that their racial secret would be revealed, and they might “lose everything”: money, reputation, friends, wives? Family lore indicates that over the years, “Uncle Tom” saw his equally white-looking, but black-identified older sister “by appointment only.” And I know that when my Uncle Paul visited New York with his white wife during my childhood, he asked to see only his sisters and brother, not their darker skinned spouses, and his niece—that was me.

But there are alternative stories too. In the Jim Crow South, my light-skinned grandmother sometimes wore a raceless mask to attend “all-white” suffrage conferences in the pre-Nineteenth Amendment years. Then she brought the information she gleaned back to share with her African American friends and peers who hoped to acquire the vote for women. On occasion, she also manipulated the racial apartheid system to acquire the best possible medical care for herself and her children. Would anyone argue with her choices in those instances?

In African American literature, one of many prominent examples of “passing” comes from James Weldon Johnson’s apocryphal Diary of an Ex-Colored Man. Johnson’s protagonist ultimately reflected back on his life as a black man passing for white and wretchedly concluded that he had “sold his birthright for a mess of pottage.”

Some may laugh and insist that those days are behind us. But present-day statistics and anecdotal stories show that with comparable resumes, the “Annes” and “Harolds” often get called in for prestigious job interviews, while the “Shaniquas” and “Duwaynes” simply do not. Black men (and women) are arrested and often assaulted by police far more often than white ones are. Other examples abound. It’s no wonder that when their physiognomies allow them to pass for white, so many of my people still think of safety, survival, and economic success and have to conclude that, when possible, being considered white in the United States is clearly preferable to being black.

Adele Logan Alexander taught for many years at George Washington University. She is the author of Ambiguous Lives: Free Women of Color in Rural Georgia, 1789–1879 and Homelands and Waterways: The American Journey of the Bond Family, 1846–1926.

Further Reading: