Medieval Artists Painted Such Things? Images that Surprise and Delight in Illuminated World Chronicles

Nina Rowe—

In the century between roughly 1330 and 1430, books known today as illuminated World Chronicles were in vogue among the upper ranks in the cities of Bavaria and Austria. Created before the era when print became widespread in Europe, these manuscript volumes were richly illustrated with hand-painted images, technically termed “illuminations.” In picture and word, World Chronicles offered expansive narratives of the historical past. But the works do not square with modern expectations for history books. Told in catchy rhyming Middle High German verse, the language of the texts is casual and engaging. And the accounts meander, moving from tales of biblical patriarchs to the adventures of Greco-Roman gods and heroes to legends of German imperial rulers, all presented as a seamless narrative. These episodes, moreover, are shot through with discursive anecdotes and often humorous dialogue, departing wildly from the source material.

The illuminations adorning World Chronicles bring to life the entertaining and freewheeling tone of the texts. And the themes of these images often surprise not only audiences unfamiliar with art history or medieval studies, but even specialists in those fields. The artists who were set with the task of illustrating the zippy World Chronicle tales experimented with style and developed new pictorial formulas, crafting dynamic modes of visual storytelling. For today’s audiences who expect medieval art to primarily present images of smiling Virgins, suffering Christs, and abject saints, or who associate medieval art with refined and restrained noble courts, illuminated World Chronicles offer much that can startle and enchant.

In the pages of these often extensively illustrated books, one finds illuminations that celebrate urban trades, revel in illicit trysts, praise the beauty of dark-skinned Africans, and disclose the hidden sins of legendary rulers. Just looking at these images can transform your understanding of the Middle Ages and suggest more broadly the ways that culture can amplify otherwise silenced voices from the past. So, I invite you to have a look at a few select episodes, to get a sense of the kaleidoscopic view of late medieval life hidden between the covers of illuminated World Chronicles.

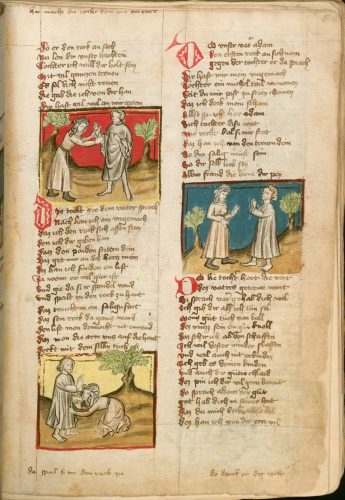

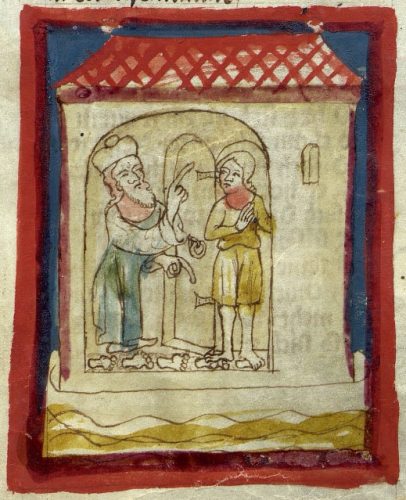

Adam is Fitted for a Garment by his Daughter, Neoma

Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cgm 250, fol. 6r (Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This page from a manuscript made between roughly 1410 and 1430 illustrates tales about the children of Adam and Eve, with a focus here on their daughter, Neoma. The episode in which Cain kills his brother Abel is long past by this point, and its moralizing lessons about the sin of envy are downplayed. Indeed, the World Chronicle narrative more or less exonerates Cain for his crime of fratricide on the grounds that this ur-murderer went on to found the first city. Other siblings are celebrated for establishing important urban trades—Tubal-Cain founds smithing, Enoch invents writing—and then Neoma is praised for her skills with textiles. This crafty daughter not only figures out how to shear sheep, spin wool into yarn, and weave it into cloth. She also makes her dad his first decent robe. In a charming series of vignettes, we see Neoma tailoring Adam’s tunic at the cuffs, marking the seams of the garment with chalk, and receiving praise from her father for his new togs.

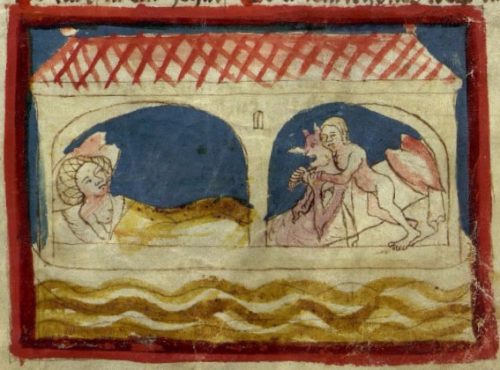

The Devil Carries Noah’s Son to his Wife’s Bedchamber; in the Morning Suspicious Footprints are Discovered

Linz: Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek, HS 472, fol. 29v (Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Linz: Oberösterreichische Landesbibliothek, HS 472, fol. 28r (Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The first illumination from a circa 1370 manuscript shown here illustrates a racy episode said to have taken place during the great Deluge. In the account, once Noah’s family has boarded the ark, along with the animals two-by-two, the patriarch makes his kin swear an oath of chastity. In order to ensure that there is no nighttime hanky-panky on the ship, Noah designates separate sleeping quarters for his sons and their wives, even sprinkling ash upon the floor between the bedchambers to better disclose incriminating footprints of any transgressors sneaking from room to room. The devil, however, has stowed away on the boat and tricks Noah’s son and his wife into engaging in a midnight rendezvous, promising to carry the son to the bed of his beloved and return him to his own cabin when the dawn breaks—Satan having the power to avoid leaving any footprints. In this image we see the devil carrying the naked lad to his lady, who awaits the assignation with breast exposed. The devil goes back on his promise in the morning, of course, brushing aside the lamenting couple with a quip more or less stating: “Why did you trust me? Everyone knows I’m a liar.” Left with no other option, Noah’s son returns to his bedroom, tracking ashes as he goes. In the second image, we see Noah puzzling over the footprints leading to the son’s bed, certain that his daughter-in-law must have padded in during the night and still be hiding somewhere. Ultimately the son and his wife confess all, and though Noah had threatened to beat mercilessly transgressors of the chastity pledge, in the end the patriarch shrugs off the misdeed, apparently recognizing the folly of trying to tamp down the fires of youthful lust.

Moses, Tarbis, and the Forgetting Ring

Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, fol. 67v (Digital image courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program)

This image from a manuscript of 1400-1410 depicts Moses with his first wife, Tharbis, a princess from the region of Kush. The lady becomes smitten when Moses leads the Egyptian army in an attack on the stronghold of Meroë, and she pledges to surrender the city in exchange Moses’s hand. The illumination presents Tharbis with all the grace and fashionable accoutrements one finds in late medieval images of European noblewomen. The artist, moreover, seems to have taken pains to emphasize the lady’s dark skin, employing a grayish-blue for her visage and hands in a manner often found in fourteenth- and fifteenth-century German renderings of Africans. We are too often taught that in the medieval era, northern Europe was a region that was homogeneously white. But that was not the case, particularly so in trade centers like the city of Regensburg—where this manuscript was made—a riverport at which shipmen from regions around the Mediterranean and further afield mingled at the docks, in the taverns, and throughout the main city squares. This image suggests esteem for the beauty of the African princess, and the accompanying World Chronicle text expresses sympathy for the lady. For Moses eventually chooses to leave her side, in order to return to his own people. Not wanting to aggrieve his sweetheart, however, he makes a magical pair of rings. Tarbis is given the Forgetting Ring, shown here, which will wipe away all memory of her feelings for Moses. Moses, however, thereafter must wear a ring that ensures he will always keep vivid his lost African love.

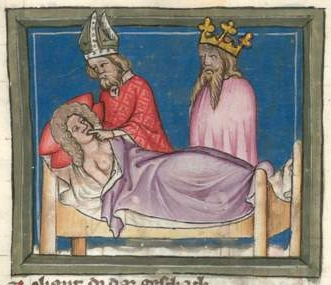

Charlemagne’s Necrophilia

Munich: Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, Cgm 5, fol. 212v (Image licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Here we get a behind the scenes look at the aftermath of Charlemagne’s shocking entanglement, not with a mistress, as we might expect, but with his dead wife. In this World Chronicle story, the first Holy Roman Emperor—a legendary ruler who was exalted and considered a saint by many—becomes victim to magical trickery. When the emperor’s wife dies, Charlemagne orders her body to be embalmed, and in the course of the process a charm is placed beneath her tongue, making her posthumously irresistible to her mourning husband. Night after night Charlemagne cuddles with the deceased queen, proclaiming that he simply cannot resist the temptation to lay with his beloved’s corpse. In this illustration from a circa 1370 manuscript, a bishop who has learned of the sinful misdeeds pulls the charm from beneath the lady’s tongue, breaking the spell and soon after reducing the dame to a pile of ash. Though released from the necrophiliac curse, the text ensures readers that the emperor carried the stain of sin for the rest of his days.

Nina Rowe is professor of art history at Fordham University.

Further Reading: