Muscat, December 1992

Sonallah Ibrahim—

As Fathy pulled the seat belt across his chest he said, “Please fasten your seat belt or we’re doomed. Traffic cops here are tough, nothing like in your country.”

I almost said that it wasn’t our country anymore, but I didn’t want to start off with an argument. I did as he asked while he sped out of the airport. I had to fumble around with the fastener, giving him a chance to make fun of me.

He was a little older than me—heftier and certainly more cheerful. He never stopped humming all types of music: Arabic, Western classical, opera, and things he had written himself while working. He was wearing a short-sleeved shirt, and I looked odd next to him in my suit. I started to take off my jacket, but he stopped me.

“Keep it on. The car’s air-conditioned,” he announced.

I told him I hadn’t expected it to be so hot, so I’d only brought winter clothes.

“No problem,” he said. “Tomorrow, we’ll buy you whatever you need.”

He drove his Japanese car down the silky-smooth highway. The way was lit by high streetlamps and had no trace of life. Prominent speed bumps slowed him. He turned the wheel a little to take them at an angle as the manuals recommend. After a few intersections, modern houses started to crop up on both sides of us, most of which were no more than one story tall.

“Always, remember this road,” he said. “It’s the main road. It’s called Qaboos Street. It’s the longest street here and it ends at the harbor, Qaboos Port.” He continued: “In a second, we’ll pass by New Qaboos City on the right.”

“Everything’s named after him?” I asked.

“Same as happens back home,” he answered. “Anyway, he has the right. This country was nothing before he took over.”

I noticed that he drove cautiously, allowing a number of cars to pass us, even though in Cairo I had known him to be reckless. He stopped at a red light, despite there being no other cars near the intersection, nor any sign of someone coming the other way. Only when I noticed a police car nearby did the mystery become clear.

As he started to move again he said, “If you want to drive here, you’ll have to take a serious driving exam and get a new license. They won’t accept the Egyptian one.”

“I have an international license,” I told him.

“It doesn’t matter,” he said. “You have to have an Omani license. They know we just give them to anyone back home.”

He started in humming the latest song by the French Algerian singer Cheb Khaled, then stopped and said, “I wasn’t surprised that it took them so many months to issue you a visa. That’s normal around here. What surprised me was that they actually gave it to you.”

It wasn’t really all that strange, though. And by now, in any case, it was all water under the bridge. I stared at the wall of darkness surrounding us for a moment, before we came upon another modern residential area, well lit and organized, a Sheraton hotel looking down from on high.

“We’re here.”

The streets were quiet, lined with parked cars and glitzy, illuminated storefronts displaying electronics, toys, clothes, and designer eyeglasses. We had to continue far down before we found a parking spot.

I liberated myself from the seat belt and he helped me get my bag out of the trunk. He asked me to wait a second while he set his car alarm.

“Are there many burglaries here?” I asked.

“Not too often. The police are vigilant. Besides, a mere whiff of a theft sends the thief off then and there.”

I was surprised. “Sends him off where?”

“Back home,” he answered. “The thief could never be Omani because they don’t need anything. It would have to be one of the guest workers, an Indian, a Pakistani, a Filipino. They’re the ones who take low-paying jobs.”

We each grabbed a handle of my suitcase and started along the street. We entered a modern building, five stories high, with a travel and cargo office occupying the ground floor. The elevator took us up to the fourth floor.

He fetched a key out of his pocket and said, “Shafiqa went to sleep two hours ago.”

He opened the door without making a sound and we entered a small living room with a dining table in the middle. We went into a room to the right that was dominated by an entertainment center holding a few books, some souvenirs, and an enormous television set. I threw myself into a chair as he picked up the remote and turned on the television. A portrait of Sultan Qaboos hung behind an announcer reading the last newscast of the day. It was an item about a flower show someplace in Europe that featured a red flower named after the Sultan. Fathy wanted to change the channel, but I told him to wait.

The announcer talked about the history of the flower, how a Dutch flower society had cultivated it after two years of trial and error. It was marked by the brilliance of its color, the purity of its smell, and the length of its stem. Its name, “Qaboos,” was an acknowledgment of the Sultan’s personal commitment to developing international relations, and His Excellency would be given this namesake flower during the celebrations of the twentieth anniversary of his rule.

The announcer moved on to the sports report and Fathy turned off the television, then started humming a contemporary American tune, shaking his full figure along to the beat with enviable grace.

“Come. I’ll show you your room.”

I picked up my suitcase and followed him to a room at the end of a long hallway. There was a couch with pillows and covers and a small desk with a computer and a big stereo. At the back of the room was a wide picture window, a piano, and an armchair.

“I’m sorry there’s no place to hang your clothes,” he said.

“It doesn’t matter. I can leave everything in the suitcase.”

“Good night,” he said.

“You too,” I answered.

I put my carry-on atop the desk and took out a pair of pajamas, slippers, a towel, and my shaving kit. I realized I had lost a wool scarf that I’d packed in anticipation of windy evenings. I remembered I had put it around my neck on the plane and hadn’t taken it off while changing planes in Doha’s cosmopolitan airport. I had it in my hand when I went into the plush restroom, but I couldn’t remember having it after that. Could I have forgotten it in the restroom?

I began to replay my trip, starting from the moment I had boarded the plane at Cairo airport. I repeated it several times. Each time it went into slow motion when I got to the moment in the men’s room at Doha airport when I stood washing my hands next to a plump young man with dark Bedouin features and a shaved head, wearing a silk shirt and baggy designer pants. He was engrossed in shaving his face and had spread out before him—in a scene of complete chaos—a collection of tubes of cream and jars and bottles of cologne and aftershave of all different sizes and colors, so that the sink looked like it was the makeup shelf for some starlet. He kept pulling out ever more paraphernalia to make himself even more fragrant.

Those disorganized movements, I now realized, had reminded me of Yaarib, who was about that same age when I first met him over thirty years ago. He, too, always took up space around him, scattering books, cigarettes, and fruit, while he waved his hands and kept barking, “Can you imagine?”

After changing my clothes, I took my shaving kit to the bathroom, where I washed up and brushed my teeth. Then I went back to the room and collapsed into the chair by the piano with a yawn. I flipped through the local papers that I had collected during the trip, unable to read anything more than the headlines. An editorial said that Kuwait had escaped the catastrophe of Iraqi occupation only to find itself in the claws of a war of attrition that was more damaging and insidious, sucking the nation’s blood drop by drop. It was shelling out billions of dollars for what was called security, cooperation, training, and defense. Another quoted the British magazine The Economist on British efforts to sell Saudi Arabia forty-eight “Tornado” bombers worth about 7 billion dollars, the second biggest sale of its kind in history. The first such deal had been worth over 15 billion—in other words, thirty-three thousand jobs for British workers in the two countries. As for the new deal, it promised to create nineteen thousand British factory jobs in order to fill all the orders by the end of the year.

I yawned again and put my newspapers to the side. I slid the window open, instantly feeling the warm breeze. I looked over the quiet street, devoid of all life, not a single movement or sound aside from the humming of the AC units. The light from the streetlamps faded a short ways off, leaving a thick blot of darkness beyond.

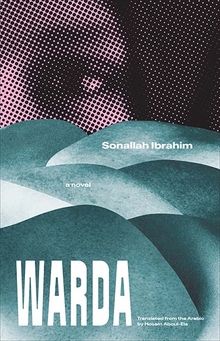

From Warda by Sonallah Ibrahim, translated from the Arabic by Hosam Aboul-Ela. Published by Yale University Press in 2021. Reproduced with permission.

Sonallah Ibrahim is a critically acclaimed Egyptian novelist. Trained in law at Cairo University, he worked as a journalist until he was arrested and imprisoned in 1959 for his political associations. Hosam Aboul-Ela is a writer, translator, and literary critic.

Further Reading: