The Architecture of China’s Economic Liberalization

Cole Roskam–

Recent news offers a reminder of the complex and challenging dynamics at work in U.S.-China relations. No relationship is more important to the future of our planet, and yet on issues ranging from climate change to COVID-19 to global trade to human rights, American and Chinese officials seem to increasingly find themselves at odds and unable to find common ground. Hostility between the two governments is perhaps at its highest level than at any point since Nixon first met Mao in 1972.

Amid current uncertainty regarding the still-emerging implications of a so-called global China for the United States and the world at large, what can we learn from the history of socialist China’s pivot toward capitalism? In particular, what might buildings reveal to us about China’s economic liberalization in all of its global dimensions?

My new book, Designing Reform: Architecture in the People’s Republic of China, 1970-1992, explores the ways in which architecture contributed to change in late-Mao and early reform-era China. China’s economic liberalization required many things—increased foreign capital, more access to international partners and markets, new technologies. It also requires spaces and systems within which new relationships, objects, ideas, and behaviors could take hold. More than physical embodiments of the unprecedented economic engagements taking place in China at the time, buildings inscribed new cultural and social practices in socialist China’s built environment and Chinese society at large.

As Chinese officials, architects, and planners worked with foreign investors, designers, and developers to define, articulate, and control the contours of the country’s new reform agenda, new forms and methods of design emerged that gave definition and meaning to the government’s more market-friendly economic policies. Historically overlooked as a consequential period in China’s architectural development, the early reform period was a vibrant if uncertain era of inspired artistic, architectural, and intellectual exploration.

The international hotel was one early and important participant in reform. In 1978, the State Council created a committee to discuss overseas investment in China, particularly in relation to the country’s tourism industry. Hotel design and construction offered a valuable means of fueling China’s economy while accommodating new investors and visitors to China. Between 1978 and 1979, for example, the number of international tourist arrivals to China jumped from 1.8 to 4.2 million people. New five-star international hotels built within each of China’s major cities, including Beijing, Shanghai, Nanjing, and Guangzhou, were subsequently proposed to support these visitors while spurring economic expansion.

Some, but not all, of these projects constituted the products of joint ventures between the Chinese government and foreign investors; many hotels were also designed and built by the country’s state-run design institutes. In both cases, however, hotels had to cater to foreign travelers with amenities and atmospheres unavailable to most of China’s own residents. Collectively, hotels quickly transformed the skylines and built environments around the country.

The Jianguo Hotel was one of the first three Sino-foreign joint ventures established by Chinese government following the advent of the reform era in 1978. The $22.6 million USD project comprised a 480-room complex planned for construction along Beijing’s Chang-an Avenue, and it represented the first large-scale, foreign-designed project to be completed in China since 1949.

Clement Chen Jr. (1930-1988), a Shanghai-born, American-trained architect who left China as a young man in 1949, was responsible for the project’s design as well as its financing. His Palo Alto-based architectural practice, Clement Chen & Associates, was known for a number of hotel projects in San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Buffalo, among others. In fact, Chen modeled his design for the Jianguo on his own Palo Alto Holiday Inn.

The hotel’s design consists of a series of individual building masses clustered around two outdoor gardens and a large, central lobby. Building heights range from five stories along the site’s east and north boundaries to one ten-story tower along the building’s west side. Sloped roofs suggest a certain vernacular aesthetic, though nearly all of the hotel’s interior furnishings were imported from abroad. The building’s exterior was unlike anything local residents had ever seen before, and crowds gathered to examine the large plate glass windows, neon lighting, and water fountain.

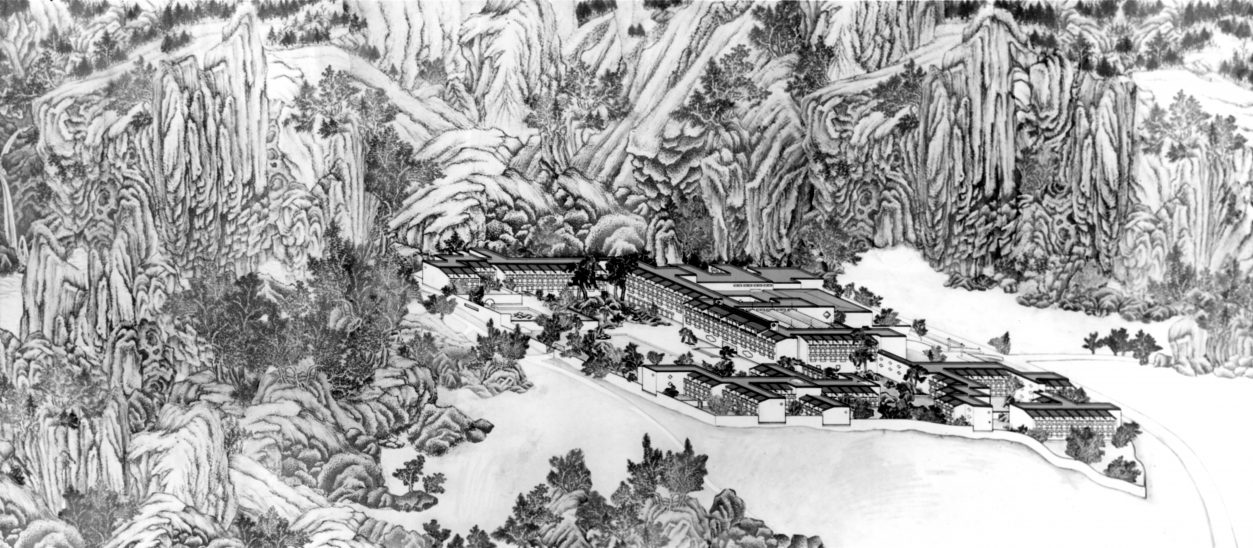

The sealed interior environment of international hotels such as the Jianguo performed slightly different functions, but with the same goals in mind. These spaces enabled smooth and uninterrupted infusions of foreign exchange into China by insulating foreign visitors from the sobering realities of socialist China and shielding average Chinese residents from the incongruous extravagances taking place inside. The Jianguo hotel lobby, for example, was designed to provide foreign visitors with all the comforts of home, and featured a coffee shop, indoor pool, as well as Justine’s, Beijing’s first French restaurant. Above the main reception desk hung Ten Thousand Miles of the Yangtze River “长江万里图” a twenty panel landscape painting measuring 1500 x 240 centimeters completed by Yuan Yunfu (1933-), one of China’s best known landscape painters at the time.

The Jianguo Hotel’s striking exterior and luxurious interior was not unique in early-reform-era China; other notable hotel projects designed with increased international exchange in mind include the east wing of the Beijing Hotel, completed in 1974 by the Beijing Institute of Architectural Design (BIAD) and led by Zhang Bo (1911-1999); I.M. Pei’s Fragrant Hills Hotel, also completed in 1982; the Becket International-designed Great Wall Hotel in Beijing (1983); the White Swan Hotel in Guangzhou, designed and built by the Guangzhou Institute of Architectural Design and completed in 1983; Nanjing’s Jinling Hotel, built in 1983 based on plans completed by the Hong Kong-based architectural firm P&T Group, and the Shanghai Centre, designed by John Portman & Associates and completed in 1990, among others.

Of China’s early-reform-era hotels, however, the Jianguo was identified as an early and important model, due in large part to its relatively simple design and rapid financial success. Upon its opening in March 1982, the Jianguo Hotel was hailed as an immediate architectural and economic achievement, and it yielded a profit within two years of operation. The hotel’s first floor became popularly known as “Wall Street” for the number of international banking representatives residing there.

Cole Roskam is associate professor of architectural history in the Department of Architecture at the University of Hong Kong.