Eminent Biography: Tim Jeal on Dr. Livingstone

Read an excerpt from Livingstone on the London Yale Books Blog

Read a piece by Tim Jeal for The Daily Beast

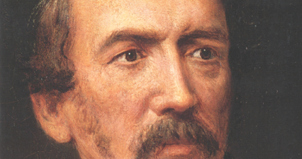

Born March 19, 1813, David Livingstone became a living myth and national hero of Victorian Britain long before his death in present-day Zambia, having lost contact with the rest of the world for most of his last years. Tim Jeal, prize-winning biographer of Henry Morton Stanley who phrased the infamous “Dr. Livingstone, I presume?”, celebrates Livingstone’s bicentenary with the release of a revised and expanded edition of his definitive biography, Livingstone. Returning to the “Eminent Biography” section of our blog, Jeal delves into the darker character of Livingstone, the man and his life lesser known—if at all—to his contemporary adorers.

Tim Jeal—

Dr. Livingstone aged two hundred

Two hundred years ago, a man was born in a decaying Glasgow tenement, who would become a unique British hero, venerated more for his supposed ‘saintliness’ than for his deeds. Sixty years later, people wept openly at his state funeral in Westminster Abbey. A missionary – as well as an explorer – he was said to have died on his knees in prayer in an African swamp, trying to bring Christianity to Africa. So when I discovered as a twenty-six year-old author that Dr. Livingstone had a darker, more complex personality than his grieving mourners imagined, I was astonished.

Aged ten he had been put to work in a cotton mill, crawling under the machines up to twenty miles a day, twisting together fraying threads. Yet he went on to become a church minister and a doctor. These astonishing feats had been achieved at the cost of a proper childhood or youth, making him isolated and intolerant of less exceptional people.

Arriving in Africa as a medical missionary in 1841, he showed his originality – and horrified his conventional colleagues – by refusing to condemn polygamy and other customs which they considered barbaric. Yet though despising his co-workers, he himself would fail as a settled evangelist, making, in eight years, one convert – a chief, who promptly took back his wives. Livingstone, I found, was not a modest man but a wildly ambitious one who had dreamed of preaching ‘beyond every other man’s line of things’ from his first months in Africa. After failing to make conversions, it was convenient for a would-be explorer to conclude that only tribes deep in the interior, who had never seen whites, would accept Christianity.

In 1851, he reached the Zambezi at the heart of Africa, but was appalled to learn that local tribes sold women and children to the mixed race agents of Portuguese slave traders. At present they were obliged to pay with slaves for the factory goods they coveted. But if he could show that boats could navigate the Zambezi from the coast, then European traders would surely come and accept payment in nuts, ivory and animal skins. So Livingstone would have to become an explorer, which he wanted to do anyway. This meant deserting his wife, whom he had married in 1845, and their three children who had accompanied him on two journeys to the Zambezi region and almost died.

Between 1853 and 1856 Livingstone crossed Africa to the Atlantic from a point on the Zambezi close to Victoria Falls (which he ‘discovered’ and named). Despite having suffered almost thirty bouts of malaria, he then tramped back across the entire continent to the Indian Ocean. During his journey, a man tried to murder a chief Livingstone was sitting beside, and gun-toting warriors of another tribe surrounded him. To the east of Victoria Falls, Livingstone found fertile and healthy country, ideal for a trading and missionary settlement, if the Zambezi proved navigable. Unwisely, he took a short-cut and so missed the impassable Cabora Bassa cataracts blocking the river. But back in England after his four thousand-mile trans-Africa epic, he was welcomed as the greatest explorer since the Tudor era.

Between 1853 and 1856 Livingstone crossed Africa to the Atlantic from a point on the Zambezi close to Victoria Falls (which he ‘discovered’ and named). Despite having suffered almost thirty bouts of malaria, he then tramped back across the entire continent to the Indian Ocean. During his journey, a man tried to murder a chief Livingstone was sitting beside, and gun-toting warriors of another tribe surrounded him. To the east of Victoria Falls, Livingstone found fertile and healthy country, ideal for a trading and missionary settlement, if the Zambezi proved navigable. Unwisely, he took a short-cut and so missed the impassable Cabora Bassa cataracts blocking the river. But back in England after his four thousand-mile trans-Africa epic, he was welcomed as the greatest explorer since the Tudor era.

But his government-sponsored Zambezi expedition failed ignominiously partly because of those cataracts, and partly because (though Livingstone could get on with his African carriers) he fell out with all the Europeans on his new expedition. Worse than that he initiated two missions, most of whose missionaries died of malaria. Their deaths led the government to recall the expedition.

Livingstone returned in disgrace to Britain in 1864. If he had been told then, that he would end his life a decade later with a vastly enhanced reputation, he would have been incredulous. But during an unsuccessful search for the source of the Nile and a simultaneous mission to expose the Arab slave trade, he showed such bravery, such powers of endurance, such faith in his mission, and such hatred of the slave trade, that admiration is still the only possible response. Thanks too to the heaven-sent arrival (as Livingstone saw it) of the Welsh-American journalist, Henry M. Stanley – the most enduring image of Dr Livingstone would be as a forgotten saint who unselfishly gave his life for Africans. It made more journalistic sense for Stanley, who idolized Livingstone and smothered his misgivings about the explorer’s vindictiveness, to present him as a neglected saint rather than as a misanthropic recluse. This depiction of angelic Dr Livingstone would be communicated to the world in his bestseller, How I Found Livingstone in Central Africa. In fact the Livingstone of his last journeys was a gentler more tolerant man than the one who had reviled the members of the Zambezi Expedition. When Livingstone had only nine carriers and five deserted, condemning him to helplessness, he wrote: ‘I did not blame them very severely in my own mind for absconding; they were tired of tramping, and so verily am I … I have faults myself’.

Livingstone returned in disgrace to Britain in 1864. If he had been told then, that he would end his life a decade later with a vastly enhanced reputation, he would have been incredulous. But during an unsuccessful search for the source of the Nile and a simultaneous mission to expose the Arab slave trade, he showed such bravery, such powers of endurance, such faith in his mission, and such hatred of the slave trade, that admiration is still the only possible response. Thanks too to the heaven-sent arrival (as Livingstone saw it) of the Welsh-American journalist, Henry M. Stanley – the most enduring image of Dr Livingstone would be as a forgotten saint who unselfishly gave his life for Africans. It made more journalistic sense for Stanley, who idolized Livingstone and smothered his misgivings about the explorer’s vindictiveness, to present him as a neglected saint rather than as a misanthropic recluse. This depiction of angelic Dr Livingstone would be communicated to the world in his bestseller, How I Found Livingstone in Central Africa. In fact the Livingstone of his last journeys was a gentler more tolerant man than the one who had reviled the members of the Zambezi Expedition. When Livingstone had only nine carriers and five deserted, condemning him to helplessness, he wrote: ‘I did not blame them very severely in my own mind for absconding; they were tired of tramping, and so verily am I … I have faults myself’.

Exploring the swampy sources of the Congo, which he hoped were the Nile’s, Livingstone became too weak to travel and died in the swamps of northern Zambia. His bravery, his ‘faithful black followers’ who carried his body to the coast and his one-man war against the Arab Swahili slavers made him that rare type of hero who enabled his contemporaries to feel pride without guilt in an age of conquests and exploitation.

Tim Jeal is the author of acclaimed biographies of Livingstone, Baden-Powell, and Stanley, each selected as a Notable Book of the Year by the New York Times and the Washington Post. He was selected as the winner of the 2007 National Book Critics Circle Award for Biography and lives in London.