The Magic of Milk

A peasant’s utopia, as imagined in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, includes a mountain of grated Parmesan cheese. Peasants do nothing else except make macaroni and ravioli all day long in the imagined fairyland. In the book of Exodus, the Promised Land is one of “milk and honey.” And according to Hinduism, during the creation of the world, the Cow of Plenty emerged during the Churning of the Ocean – literally the changing of the white ocean into butter. Deborah Valenze explains in Milk: A Local and Global History, how the “elixir of immortality” changed from a staple of the gods to a staple of nutrition textbooks.

A peasant’s utopia, as imagined in Giovanni Boccaccio’s Decameron, includes a mountain of grated Parmesan cheese. Peasants do nothing else except make macaroni and ravioli all day long in the imagined fairyland. In the book of Exodus, the Promised Land is one of “milk and honey.” And according to Hinduism, during the creation of the world, the Cow of Plenty emerged during the Churning of the Ocean – literally the changing of the white ocean into butter. Deborah Valenze explains in Milk: A Local and Global History, how the “elixir of immortality” changed from a staple of the gods to a staple of nutrition textbooks.

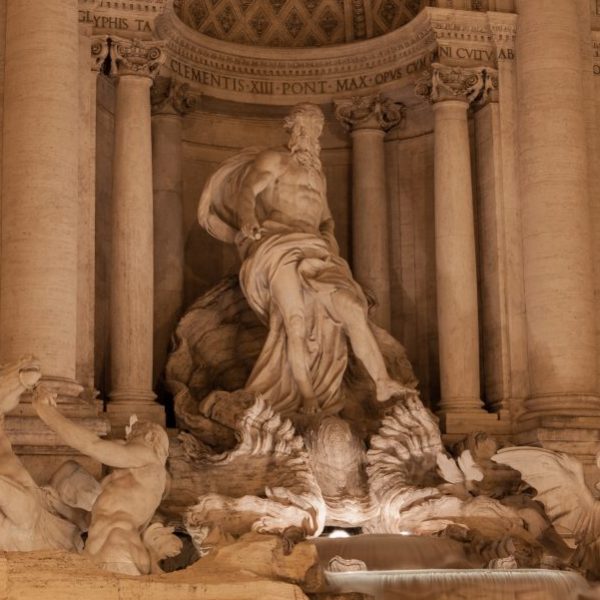

The Cow of Plenty is one of many sacred females associated with the “virtuous white liquor’s” powers. Valenze shows us various forms of ancient heavens and their inhabitants’ fascinating relationships with a Great Mother, or a “benevolent cow,” or a milk goddess. Isis, most famously a goddess of ancient Egypt, was “the source of the milk of life,” and the Virgin Mary modeled fecundity and piety for medieval women. Juno, the Roman queen of the gods, created the Milky Way when her breast milk was scattered accidentally when she woke up to a rather awkward situation: her husband, Jupiter, had attempted to feed his illegitimate son, Hercules, at her breast while she slept. Interestingly, Jupiter’s Greek counterpart, Zeus, nursed from the goat Althea as a baby.

Although “the culture of milk” lost some of its mystical qualities through history, in its secular role it was (and is) no less “magical.” Doctors admired it through the centuries, from George Cheyne’s milk diet (at one point the physician and writer weighed 448 pounds) in the early eighteenth century to the Victorians’ prescriptions of milk-soaked biscuits for their patients. The Dutch came the closest to actually reproducing Dairy-land here on earth during, appropriately enough, their Golden Age. With Cheesetopia finally realized, Dutch painting actually depicted the “mountains of food” – which included if not Parmesan at least other forms – that “stood as bountiful evidence of God’s providence.”

Even today, Valenze points out, milk still satisfies “[t]he wish for a miracle food” by some foodie camps. Its constant presence in our “dairy-rich Western countries,” she notes, is just as extraordinary as the food itself. We may not be able to produce endless quantities of butter, which was Saint Brigid’s first recorded miracle, but perhaps that’s just because mass-production has already beat us to the magic.

thanx for posting gd blog