3@2 Interview: Peggy and Murray Schwartz on the Dance of Pearl Primus

Peggy & Murray Schwartz, credit Stan Sherer

In our newest 3@2 Interview, we asked Peggy and Murray Schwartz, professor emeritus at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and professor at Emerson College respectively, about their intimate knowledge of legendary dancer, Pearl Primus (1919-1994). A noted anthropologist in her tireless studies of Afro-Caribbean cultures and folklores and her pioneering concepts of dance anthropology, Primus incorporated social and racial protest into her choreography and became a politically significant figure as well. She briefly sympathized with the Communist Party and toured the American South with a mixed race company. The FBI created a file for her even before the McCarthy era, and she was active in the campaign to end Jim Crow laws. In their new book, The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus, the Schwartzes recall their first meeting with the dancer in 1980 which began a deep friendship that lasted until her death in 1994. In these years there were countless phone calls, dinners, academic discussions, and even surprise visits that shaped their perspective of the woman largely responsible for bringing African dance to contemporary American audiences.

Yale University Press: Did you decide to write about Pearl Primus during her lifetime?

Primus family portrait, New York, 1920s. Pearl Primus (right), Source: Schwartz Collection

Peggy Schwartz & Murray Schwartz: The decision to write a biography of Pearl Primus crept up on us. We sat with her, each of us, many times as she told stories, often the same ones, in the manner of a griot. Oral traditions – you need to hear the story at least three times. It was as though she was preparing us for the role of biographers by telling us the names of friends, colleagues, places, and traditions. But there was never talk of writing her story. Some of these conversations took place in Murray’s office, some in our kitchen, some in a car, travelling from here to there, occasionally in hotel rooms when at conferences together. As the need to write about her took hold after her death, we wished we’d interviewed her more systematically in her life. But such is not the tradition. She would have resisted the formality. She died at the age of 74. As with a parent, you always think there will be more time. She was so active and vital a presence in our lives, we never imagined our life without her.

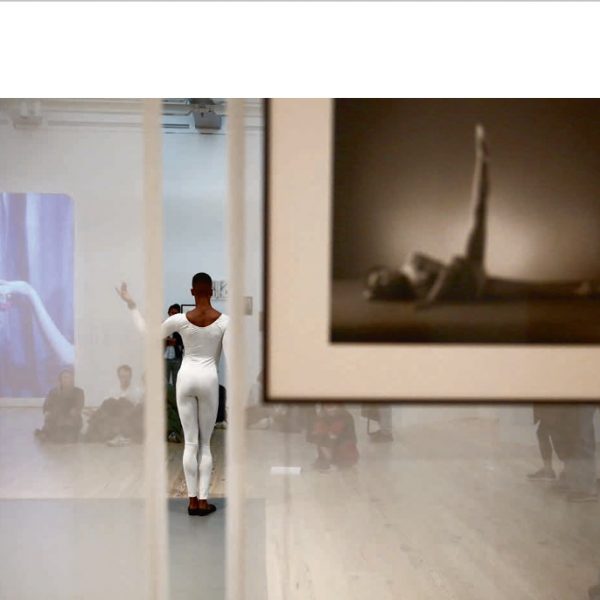

YUP: Your book describes Primus’s dances in words, although they are essentially wordless subjects. Was it difficult to find ways to communicate the images and themes of her work?

PS & MS: The meanings of dance exceed the capacities of words, as the body exceeds language. Describing the dances was a challenge Peggy undertook initially, followed by our up-and-back editing process. Although not formally a dance critic, Peggy has experienced a life in dance, from early childhood on. Wonderful teachers taught vision and clarity. Years and years of teaching honed a vocabulary for description. The challenge in describing Pearl dancing was that for the most part there are no films of her performances of the famous modern dance protest solos, “Strange Fruit,” “Hard Time Blues,” “Negro Speaks of Rivers.” There are some films of these as performed by dancers to whom she imparted these masterpieces. Talking with a dancer she coached and who later set these solos on Peggy’s students gave insight, as did interviewing professional dancers on whom she set African choreographies.

PS & MS: The meanings of dance exceed the capacities of words, as the body exceeds language. Describing the dances was a challenge Peggy undertook initially, followed by our up-and-back editing process. Although not formally a dance critic, Peggy has experienced a life in dance, from early childhood on. Wonderful teachers taught vision and clarity. Years and years of teaching honed a vocabulary for description. The challenge in describing Pearl dancing was that for the most part there are no films of her performances of the famous modern dance protest solos, “Strange Fruit,” “Hard Time Blues,” “Negro Speaks of Rivers.” There are some films of these as performed by dancers to whom she imparted these masterpieces. Talking with a dancer she coached and who later set these solos on Peggy’s students gave insight, as did interviewing professional dancers on whom she set African choreographies.

But equally important was uncovering a video of a concert in 1979 in which she performed and re-staged several of her most famous group pieces. Watching her perform “Michael Row the Boat Ashore,” a piece that mourns the death of four young girls in the 1963 bombing of a Birmingham church gave depth and reality to her incredible power and essence as performer. Dance at its most basic. A woman, a mother, sits immobile and alone on a chair. One by one dancers enter and surround her, attempting to lift her back into her life, to help her grieve her lost child so that she herself can live. As Pearl walks from the place on stage where she describes the dance she was about to perform to where she becomes the mother, immobilized by grief, one watches her transformation with astonishment.

YUP: You have been able to present us with some of Primus’s own poetry and show us that she valued different art forms, from dance to African clothing. How did art affect her life outside of dance?

Pearl and Alphonse Climber, 'Folk Dance', Pearl Primus Collection, American Dance Festival Archives

PS & MS: We are reminded of W.B. Yeats’ line, “How can we tell the dancer from the dance?” Pearl presented her self as a work of art, her African dress but one facet of meaningful expression. When a young reporter in Buffalo asked the meaning of her costume, i.e. her everyday style of dress, she replied with characteristic wit, “I’ll tell you the meaning of mine if you tell me the meaning of yours.” As early as her high school years, she was mastering the rhythms and ironies of poetry to convey self-aware relations to nature and society. Her African poetry is a beautiful evocation of the richness and poignancy of her experiences there, and she carried this eloquence into her telling of stories in all kinds of settings. For Pearl anthropology was not only a field of study, it was also and simultaneously a way of living.

As an artist there’s a way in which Pearl (and we explain in the book that from our first meeting she was Pearl to us, not Dr. Primus or Mama Pearl or Professor Primus) was her own greatest creation. Whether sweeping down the aisle of an elementary school auditorium at the start of a lecture-demonstration with rhythmic drums announcing her arrival, colorful fabrics swirling around her accented by bright beads, arms festooned with bracelets and gesturing greetings to an excited audience, or entering downstage right in a more formal setting to introduce a concert or a dance about to be performed, the message she wanted to convey was one of authenticity. Authenticity. As she stood and waited for applause to fade, her dramatic entrance announced, “Here I am, here we are, here is a journey on which I am singularly qualified to lead you. Follow me. Join me in the rhythm, the color, the texture, the mood and nuance of the African cultures I embody.” Only then would she speak her words of welcome and introduction.

To learn more about Primus’s legacy and keep track of The Dance Claimed Me: A Biography of Pearl Primus, you can follow on Facebook.