Melissa Harris-Perry Talks with Yale Press About Sister Citizen

You’ve read her column in The Nation, seen her guest hosting the Rachel Maddow Show, even found her at our office; now, the week before the publication of Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, we sit down with Melissa Harris-Perry to ask a few key questions about what lies at the heart of her new book: the historical, political, and emotional formation of black women’s identities in America, and how their participation in our society matters to all.

You’ve read her column in The Nation, seen her guest hosting the Rachel Maddow Show, even found her at our office; now, the week before the publication of Sister Citizen: Shame, Stereotypes, and Black Women in America, we sit down with Melissa Harris-Perry to ask a few key questions about what lies at the heart of her new book: the historical, political, and emotional formation of black women’s identities in America, and how their participation in our society matters to all.

Yale University Press: In writing about black women’s politics, why did you focus on psychological and emotional questions rather than resource inequalities, institutional practices, or traditional forms of political participation?

Melissa Harris-Perry: I wanted this book to contribute to our understanding of black women as citizens. At first, I expected to write a more traditional political science text about women who organize in communities and run for office. But my research efforts kept bringing me back to black women’s internal emotional experiences. The women I interviewed were keenly aware of race and gender barriers, resource disparities, and limited opportunities, but when they talked about themselves as Americans, they focused on psychic pain, emotional stress, debilitating shame, and the pressure to live up to unrealistic expectations. Many felt that they were trying to “do politics” in an environment where no one was willing to see them accurately or compassionately.

YUP: Sister Citizen discusses several stereotypes about black women. What are they, and why did you choose to explore them?

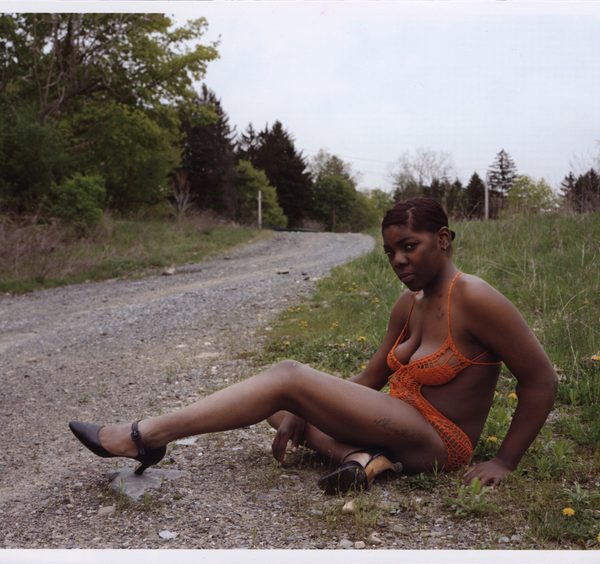

MH-P: In Sister Citizen I focus on three of the most pervasive and damaging historical stereotypes: Jezebel, Mammy, and the Angry Black Woman (Sapphire). Jezebel is an old myth asserting that black women are hypersexual, lusty, and wanton. This stereotype continues to influence public policy discussions about welfare assistance and reproductive rights. Mammy is the hypercompetent but completely nonthreatening black woman. The image of the devoted Mammy who uses her talents and skills to benefit the white domestic sphere is an epic stereotype promulgated in advertising, popular culture, and politics. Sapphire is a more contemporary archetype characterizing black women as aggressively and irrationally irate. It can be difficult for black women to get a fair hearing of their views if their passionate expressions are filtered through this negative assumption. Finally, I explore the myth of the strong black woman. Unlike the other stereotypes, which black women agree are negative and false, many African American women both believe and embrace the idea that they are endowed with a superhuman capacity to conquer overwhelming challenges. We might see this myth of strength as a positive counter to the negative stereotypes, but there are adverse consequences for black women who are determined to don the mantle of strength. Overall, I try to understand how black women’s attempts to manage both the negative stereotypes and this presumably empowering myth can influence how they feel as they approach their political lives.

MH-P: In Sister Citizen I focus on three of the most pervasive and damaging historical stereotypes: Jezebel, Mammy, and the Angry Black Woman (Sapphire). Jezebel is an old myth asserting that black women are hypersexual, lusty, and wanton. This stereotype continues to influence public policy discussions about welfare assistance and reproductive rights. Mammy is the hypercompetent but completely nonthreatening black woman. The image of the devoted Mammy who uses her talents and skills to benefit the white domestic sphere is an epic stereotype promulgated in advertising, popular culture, and politics. Sapphire is a more contemporary archetype characterizing black women as aggressively and irrationally irate. It can be difficult for black women to get a fair hearing of their views if their passionate expressions are filtered through this negative assumption. Finally, I explore the myth of the strong black woman. Unlike the other stereotypes, which black women agree are negative and false, many African American women both believe and embrace the idea that they are endowed with a superhuman capacity to conquer overwhelming challenges. We might see this myth of strength as a positive counter to the negative stereotypes, but there are adverse consequences for black women who are determined to don the mantle of strength. Overall, I try to understand how black women’s attempts to manage both the negative stereotypes and this presumably empowering myth can influence how they feel as they approach their political lives.

MH-P: Why does Hurricane Katrina occupy such an important place in this book?

I believe that the political and psychological aftermath of Hurricane Katrina revealed critical fissures in our national life. For me, New Orleans is ground zero for understanding black women as citizens and as survivors. It is why I now make the city my home and why I have initiated at Tulane University a program on gender, race, and politics in the South.

YUP: The last chapter deals with Michelle Obama. Why?

Michelle Obama holds no official political position, has never run for office, and has no personal history of political organizing, yet she is profoundly important to understanding the challenges that black women face in American public life. Her management of her public image is instructive about how black women navigate race and gender stereotypes. Because she is First Lady, her efforts to gain accurate public recognition are emblematic of those engaged in by many black women.

Melissa V. Harris-Perry is professor of political science at Tulane University, where she is founding director of the project on gender, race, and politics in the South. She is a columnist for The Nation magazine; and she is a contributor to MSNBC, appearing as a bi-weekly guest on the Thomas Roberts Show and a frequent guest on the Rachel Maddow Show and The Last Word. You can read more about her at www.melissaharrisperry.com and follow updates from Sister Citizen both on Facebook and Twitter.