Lest We Forget: Integrated Schools, Integrated Lives

Sarah Underwood—

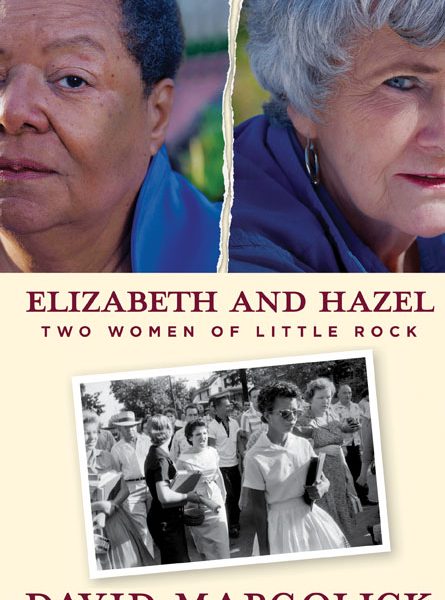

Think back to yourself at age fifteen. That’s the age both the women profiled in David Margolick’s Elizabeth and Hazel: Two Women of Little Rock were when Will Counts took his famous photograph. Many people assumed Hazel Bryan, the screaming, hateful white girl in the picture, had to be twice the age of the stoic black schoolgirl, Elizabeth Eckford. They were, however, the same age, only Hazel had picked a dress hoping to look “more sophisticated and maybe more promiscuous than she really was.” Instead, the public would, for many years, think she was older and should have been more responsible.

They didn’t know her family was poor, that she wanted find a way to leave home, and that her sophomore year of high school, she’d swallowed enough aspirin to require hospitalization. She was also one to get “caught up in the moment,” given to “histrionics”: she was a girl from a Fundamentalist Christian family who wanted to be a performer. None of that excuses her behavior, but it helps us to understand why her face is often more easily recalled than any of those of the Little Rock Nine.

They didn’t know her family was poor, that she wanted find a way to leave home, and that her sophomore year of high school, she’d swallowed enough aspirin to require hospitalization. She was also one to get “caught up in the moment,” given to “histrionics”: she was a girl from a Fundamentalist Christian family who wanted to be a performer. None of that excuses her behavior, but it helps us to understand why her face is often more easily recalled than any of those of the Little Rock Nine.

How many of us, raised the way Hazel was and prompted by a similar personality, would have behaved differently? Each of us hope we would behave better than her, better than anyone else in that crowd, but at fifteen, perhaps caught up in mob mentality, we might not have. But history could excuse one moment. Elizabeth did, accepting Hazel’s telephone apology when they were twenty-one. A couple decades later, the two even became friends, attending speaking engagements and even flower shows together. There were many reasons the friendship eventually faded—integration left scars of which they weren’t always aware—but one was that Hazel’s hateful words were not limited to one moment.

What happens when a central figure of a historical event does not remember all of her own history? The famous photograph was not Hazel’s only exposure in the media during the forced integration of Central High School. For Hazel and her two girlfriends, “the attention proved addictive,” and she told reporters the next day, “Whites should have rights, too!…Nigras aren’t the only one that have a right!” It was these later comments to reporters that would come to bother her new friend Elizabeth in later years. Hazel apologized for yelling at Elizabeth all those years ago, but she could barely remember the events of that day or the day after. She could not apologize for the interviews she could not remember giving. She suggested she had a form of “amnesia” about those events, even wondering if hypnosis could help. To Elizabeth, for whom those days were so difficult that decades later the horror still rendered her speechless, it was as if Hazel was speaking a foreign language.

Integration was more than a moment in history, and so was both women’s involvement. For a while, Hazel’s motto was “my life is more than a moment.” After the women took a photo together demonstrating their reconciliation, Elizabeth told Hazel something similar, if a little more blunt, “Don’t make too much of this picture.” A picture might say a thousand words, but it can never capture the thousand more moments that will truly define its subjects.

Sarah Underwood is a graduate of the College of William and Mary and a former Yale University Press intern. Her column, Lest We Forget, appears on the Yale Press Log.