An Art History of Israel

Israel: An Introduction, new from Yale University Press, provides a comprehensive look at a nation that has always been at the center of the world’s stage, tracing its tumultuous history and political realities while providing an overview of its economics, population, and culture. In this excerpt from the book’s chapter on culture, Barry Rubin, a leading historian of the Middle East, describes the tradition of Israeli visual art, guiding the reader from the abstract painting and socialist realism of the nation’s early years to the apocalyptic themes prominent in artworks from the last several decades.

Israel: An Introduction, new from Yale University Press, provides a comprehensive look at a nation that has always been at the center of the world’s stage, tracing its tumultuous history and political realities while providing an overview of its economics, population, and culture. In this excerpt from the book’s chapter on culture, Barry Rubin, a leading historian of the Middle East, describes the tradition of Israeli visual art, guiding the reader from the abstract painting and socialist realism of the nation’s early years to the apocalyptic themes prominent in artworks from the last several decades.

Barry Rubin—

In 1906, the Bezalel School was founded in Jerusalem to train professional craft workers and artists. To it can be traced the beginnings of Israeli visual art. By the 1950s, the major groups in Israeli art were divided between those emphasizing the universal-aesthetics dimension of artwork (New Horizons) and those expressing the local dimensions in relation to Israel’s history and society (social realism and the Group of Ten).

New Horizons (Ofakim Hadashim), established by a group of artists in 1948, dominated the art scene during Israel’s first two decades. At first, it was influenced by expressionism and cubism, as well as by the Jewish Paris school—by Chaïm Soutine, Michel Kikoïne, and Marc Chagall, among others. Like many Israeli cultural movements, the group was torn between universalism and the specific reality of local society.

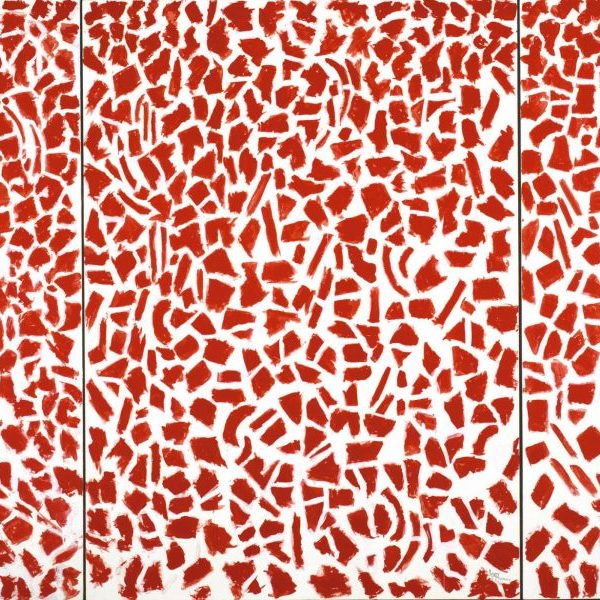

Eventually New Horizons moved toward abstract art, and this became the main style of artistic expression in Israel, perhaps even its canonical high art. New Horizons was perceived as a movement that emphasized universality rather than Israel’s specificity. A 1958 exhibition held in honor of the state’s first decade included works by New Horizons artists, among them the painting Power (Otzma) by the leader of the group, Joseph Zaritsky (1891–1985). When Prime Minister Ben-Gurion attended the opening, he was disturbed by the painting and asked to have it moved to a less central location since he thought it not representative enough of Israeli culture.

At the other end of the artistic spectrum were socialist realist artists, who saw their work as connected directly to society. They created representations of transit camps, demonstrations, workers, industrial developments, and life on the kibbutz and in the city. Some emphasized a link to nationalist values through symbolic images. Unlike New Horizons, these artists turned to Italian and Mexican art as well as to American painting, such as that of Ben Shahn, and Picasso’s painting Guernica, as sources of inspiration. This heterogeneous group consisted of artists from the kibbutz, like Yohanan Simon, Shraga Weil, and Shmuel Katz; artists who had left the kibbutz, like Avraham Ofek and Ruth Schloss; and artists working in the city, like Naftali Bezem, Shimon Tzabar, Gershon Knispel, and Moshe Gat. Social realists criticized New Horizons for being egocentric and reactionary and for merely playing with form.

Another group working in opposition to New Horizons was the Group of Ten (1951–1961), which attacked abstract painting. Most of the members of the Group of Ten were former students of Yehezkel Streichman and Avigdor Stematsky, major figures in New Horizons. The Group of Ten employed figurative painting to look at local ways of living and local landscapes. Unlike the social realists, they avoided any overt social or political agenda.

The ninth exhibition by New Horizons (1959) was held at the Helena Rubinstein Pavilion at the Tel Aviv Museum of Art, and it showed not only the strength of the group but also the beginning of its demise. Others exhibited works different in spirit from the abstraction of New Horizons. These included sculpture, such as Igael Tumarkin’s Panic over Trousers: The artist immersed his work trousers in polyester and hung them on the work’s black-colored surface to look like a walking ghost. He stamped his hand on the sides, and those marks, together with the red marks on the surface, constitute a cross-composition in which the artist presents himself as a sacrifice.

An artistic organization of ten artists founded the group 10+, whose members included Raffi Lavie, Uri Lifshitz, Buky Schwartz, Ziona Shimshi, and Benny Efrat. Each retained his or her own artistic vision. Together they would set a theme for an exhibit (the color red, the figure of Venus) and invite others to participate—hence the “plus” in their name. They were influenced by the American Pop Art of Larry Rivers and Robert Rauschenberg in their use of materials and injected irony, humor, and sophistication into Israeli art. They used photographs, everyday objects, dolls, towels, and other materials innovatively to create collages and assemblages and combined different media: poetry, theater, cinema, electronic music, and fashion. Their attempts to expand the limits of art were initial steps in the anti-institutional artistic activity characteristic of the 1970s.

Postmodernism, Rebellion, and the Radical Critique

After the 1973 war, art became more political and critical in its relation to society. One event was the rebellion in the Bezalel Academy, when radical teachers abandoned painting and sculpture in favor of alternative, conceptual-material art. In the end, teachers such as Micha Ulman and Moshe Gershuni were dismissed. The institution returned to its emphasis on painting, but some students from the rebellion period—Yoram Kupermintz, David Wakstein, and Arnon Ben—retained the spirit of political art, which would become central in the future.

Artists in 1970s Israel used such industrial items as rust-proof wires in sculptures and such materials as margarine to create images with random effects. They also criticized art institutions in their work. Thus, Benny Efrat blocked the entrance to his exhibition (Information, 1972) in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem; Moshe Gershuni painted graffiti on the walls of the Julie M. Gallery.

The human body, suppressed by the abstract emphasis of early Israeli art, also returned to center stage in the 1970s. In 1973, Pinchas Cohen-Gan carved a male figure on the walls of the Yodfat Gallery and called it Place as a Physical Position. This digging into the wall in search of a nonexistent object was a testimony to the artist’s process of defining and searching for his own identity as a Moroccan, a refugee, and an artist, but it also indicated the disorientation of Israel in general.

Art in this decade questioned the artist, art object, and Israel as a means of improving social, historical, and political circumstances. Most of the artists were aware of the utopianism of their performances. In 1974, Michal Na’aman reflected on the way the state dealt with its borders by placing two signs on the Tel Aviv beach bearing the words “The Eyes of the Nation.” The signs were directed westward, toward the water, and were painted in the colors of the sea. The text came from a soldier’s words during the last days of the Yom Kippur War and related to the capture of Mount Hermon in the Golan Heights.

A key concept of artists and cultural figures during the 1980s and 1990s, inspiring much of their radical view, was the belief that Israel could easily obtain peace if it only took the proper steps. The other side was either ignored, given sympathy, or treated as if it were not a real threat. Instead, the artists bitterly and angrily blamed conservative and religious forces for ruining Israel and extending the conflict, especially given their belief (and fear) that the conflict would bring disaster to the country.

In his 1981 painting Sing Soldier, Gershuni inscribes the lyrics of a 1942 song by the poet Ya’akov Orland, “Arise, Please Arise.” The poet encouraged the reader to go out and fight; Gershuni erases the lyrics with layers of color that express an intense mental state and blood. In his work Isaac Isaac (1982), Gershuni refers to the Biblical story of the binding of Isaac in the context of the First Lebanon War. Gershuni moves between the abject and the sublime, Christianity and Judaism, rationalism and emotionalism.

The 1982 Lebanon War and the First Intifada inspired critical political messages. David Reeb, for example, created a long series of paintings based on superimposing the violent reality in the West Bank and the Gaza Strip on the calm reality within Israel. Reeb painted cartographic images of Israel without including the territories captured since the 1967 war. In his work Green Line with Green Eyes (1987), he contrasted the Tel Aviv shore with a scene from the intifada. The painting is covered with images of eyes staring back at the viewer. He uses the colors of the Israeli and Palestinian flags and hints at a spreading blindness. Created by Pamela Levi in 1983, following the Lebanon War, Dead Soldier Painting depicts the nonheroic presence of death.

Photography

Another important development of the 1980s was the rising status of photography. Adam Baruch, Anat Saragusti, and others equated documentary photography with art and gave it an important role in describing political and social reality. Micha Kirshner shot a portrait of Aisha El-Kord from the Khan Yunis refugee camp in a series of intifada portraits that he photographed in his studio. Aisha El-Kord was a child injured in the eye by a rubber bullet. She appears in the photograph with her mother in a pose evocative of a pietà.

The contrast between calm life and violent instability is a common theme in works of this period. A good example is Gal Weinstein’s installation Slope, which depicts small houses with red roofs buried in dark soot. The scene looks like Pompeii after the volcanic eruption, suggesting that Israel is living its last days and will soon collapse.

Similar to this is Sigalit Landau’s Swimmer and Wall (1993), in which a tiny shiny doll swims into a wall, her head exploding in the violent encounter. The sweetness of the doll bursts when it crashes into reality. The symbol of the decade, suggested the curator of the 1990s exhibition at the Herziliya Museum of Contemporary Art, was youth aware of its own transience, of its own mortality. In a confrontation with death, there is an attempt to hold onto youth while maintaining awareness of the inferno to follow.

Khaled Zighari’s Head to Head (1995) presents a soldier and a Palestinian civilian facing off. They are twins in a dance. A later version of this duet can be seen in Sharif Waked’s Jericho First (2002), a series of thirty-two paintings whose point of departure was an image from the Hisham Palace in Jericho depicting a lion attacking a doe. The series develops as the violent act proceeds, and the images become denser until at the end, the lion and the doe become one body in which one can see the hanging leg of the doe. The image hovers between comic strip and abstract painting and represents a violent, mythical world filled by conflicting concepts of strong and weak, good and evil.

In 1997, Meir Gal exhibited Nine Out of Four Hundred: The West and the Rest. This is a color photograph that portrays the artist bursting from a dark background or perhaps immersed in darkness. The artist holds in his hand a history book from the 1970s, written by Shmuel Kirshenbaum. Of 400 pages, only nine are dedicated to the history of non-European Jews, and these are the pages that he holds in his hands. The rest of the pages are hanging down. This is an effective photograph presenting a sharp message that the Mizrahim have been erased from the pages of history.

The apocalyptic mood continued into the new century. The visitor entering Sigalit Landau’s October 2002 exhibition The Country at Tel Aviv’s Alon Segev Gallery experienced a strong sense of disorientation. Descending into the basement, the visitor entered one of Tel Aviv’s roofs as if excavated by archaeologists. The installation included three figures: one picking fruit, a second carrying fruit, and the third an archivist or observer who looked like an ancient Egyptian figure in the act of writing. The forbidden or poisoned fruits were fashioned from newspapers; the three figures looked like the living dead; their bodies had exposed muscles without flesh. The basement space was like a representation of hell.

Some contemporary art reveled precisely in its lack of meaning and even embraced escapism. In Landscape and Jerusalem (2007), for example, Eliezer Sonnenschein painted a fantastic landscape combining apocalyptic images of early European painting with the saccharine-sweet language of posters from the 1970s, together with animation effects.

Such works do not characterize all or most of Israeli art. The 1990s and the early twenty-first century also brought a new interest in beauty. The kind of magical realism that had become popular in literature also pervaded art with the use of illusion, spectacular effects, and even the use of religious ideas.

Excerpted from Israel: An Introduction, Chapter 7: “Culture;” Copyright © 2012 by Barry Rubin.

Barry Rubin is professor and director of the Global Research in International Affairs Center at the Interdisciplinary Center, Herzliya, Israel. He is also editor of the Middle East Review of International Affairs and author of numerous books on the Middle East.

Reblogged this on THE GRAPEVINE.