Lost Without Translation: Margaret Sayers Peden on Work as a Translator

Margaret Sayers Peden, translator of Fernando de Rojas’ fifteenth-century classic La Celestina, among dozens of other books, considers here the joys and pleasures, challenges and frustrations of literary translation. Often regarded as the first European novel and second only to Don Quixote in its importance to Spanish literature, Celestina is now available in paperback from the Margellos World Republic of Letters. Be sure to sign up on the WRL site to receive full e-mail updates and interviews with authors and translators in advance.

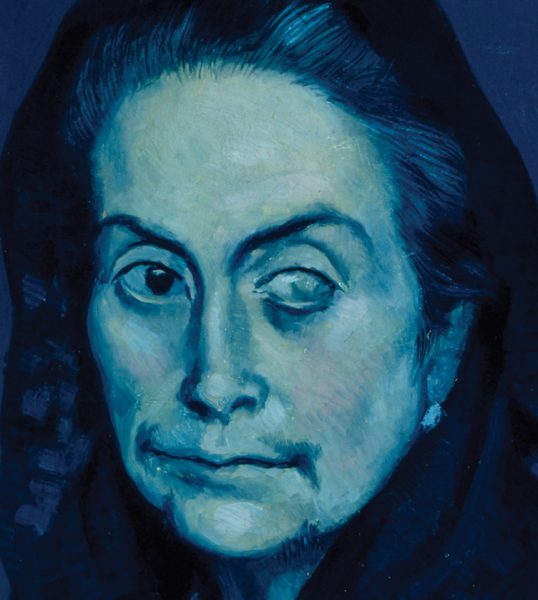

Margaret Sayers Peden—

My Work as a Translator

I had a fortunate experience as I began translating. It happened during my Ph.D. program, begun in 1964. I was writing on a Mexican playwright, Emilio Carballido, when I came across a small novel he had written, one of only two. I liked the book, largely due to the structure, and one evening was discussing it with my husband, William Peden, who died in 1999. I was telling him how interesting the small novel was and Bill said, “You know I don’t read Spanish, why don’t you translate it for me?” So I did.

I had never done any translation. In the Midwest there were no courses, no organizations, nothing connected with that endeavor. But why not? It was fun. I worked on it amid classes and teaching and running a house, and, what do you know?, ended up with a small novel in English. So what do I do with it now, I wondered—I was a true novice. Publish it, I guess. I went to the library to see who was publishing Latin American literature.

After a little research I sent The Norther, Carballido’s El norte, to the University of Texas Press in Austin, who accepted the novel. That was pleasure enough, but in addition the editors made no changes in the manuscript I’d sent them. No editing, no corrections or suggestions. This was a dream, but one that would never be repeated among the sixty-five books I’ve translated. I thought that was how one delivered a translation, often wishing it was that simple.

After a little research I sent The Norther, Carballido’s El norte, to the University of Texas Press in Austin, who accepted the novel. That was pleasure enough, but in addition the editors made no changes in the manuscript I’d sent them. No editing, no corrections or suggestions. This was a dream, but one that would never be repeated among the sixty-five books I’ve translated. I thought that was how one delivered a translation, often wishing it was that simple.

I fell into a career I had never dreamed of following. After the 1970 publication of The Norther, my translating continued, accompanying my teaching, until my retirement from the University of Missouri in 1989. The teaching and translation fed one another, books used in courses not infrequently attracted me sufficiently to translate them, and in return books I found in my Latin American literature in translation classes alerted me to good subjects for the more traditional classroom.

I do not believe I have ever devoted my time to a book I didn’t like, though there has been a broad difference in the pleasure obtained from the process of translating: everything from working with a totally cooperative author, with authors who knew English very well and were happy to answer questions and untangle problems, with authors who knew no English at all and preferred not to be involved, and with authors who knew a little English but thought they knew it as well as their own, and thus were sure they were able to choose the best for their book. All these authors were living. Working “with” authors who were not alive was a different matter. Some inevitably faded into their time periods, but others survived so strongly that they seemed more present, more dynamic, than writers still with us. Cesar Vallejo for his vitality, his language, his social ideals. Juan Rulfo for his mystic novel Pedro Páramo; he wrote very little else but didn’t need to. Pablo Neruda for the richness of his poems, and, like Cesar Vallejo, for his humanitarianism. Francisco Rojas, who wrote Celestina, to whom I am deeply indebted for giving me a view of life in the 1600s, the culture, and the moral and ethical scales. And Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz seemed to talk to me. I could hear her, truly so; I am deaf in my right ear and I never heard her voice except in my good one.

There are endless questions difficult to answer asked in public lectures, classroom discussions, and with interested friends in casual conversation. How does one translate? Do you believe that an eighteenth-century book should be modernized or kept in its time period? What do you do with refrains, proverbs, with children’s rhymes, songs, curses, slang, all those things common to one culture and unknown in another? All one can say is that the solutions are something different with each book, which is one of the things that makes my work so fascinating.

One thing about translation is that there is seldom, very seldom, only one way to transfer a sentence from one language to another. There are so many variables, beginning with the choice of words, and the added problems that lead us to desperation. And there is no “right” or “wrong” in translation other than not reading the original correctly. The simplest answer regarding comparisons is “better” and “worse.” Those judgments are easily reached. And if one has any doubts about these truths, he should give fifteen people the same lines in Spanish, and then check the translations.

It was difficult to convince my colleagues that translation is a scholarly pursuit. One senior professor, for example, chided me by saying that what I did was entertaining, but that if I wanted to succeed in our profession I should give it up. (A pox on him.) Another advised our students not to work with me on their Ph.D. if it meant touching on translation. There were constant allusions to what little weight translation had when considering elements for the successful completion of a Ph.D., as well as for promotion and tenure. These attitudes were beginning to change as I reached retirement, but actually they had very little effect on my fascination with translation.

There is something so engaging about this work that one looks forward to settling down at the desk or computer to begin. There is a period of analyzing the pages and consciously, or subconsciously, begins with writing a list of what may present problems in this book and what is neeed to confront them. Is the novel, or the poem, written in non-standard Spanish? Will I need to familiarize myself with a specific historical period? Is a major character a psychiatrist? A musician? A day laborer? A professor? Every professional or societal group uses language in a different way. These variables are greatly complicated by time period, even in contemporary speech, and worse if not in contemporary time. But once when translating a novel by Carlos Fuentes, his colossal Terra Nostra, I had to ask him about a phrase dating from the modern era in France. “Sorry,” he told me. “That Parisian slang changes so quickly that I’ve forgotten what these wordssay. Just make something up.”

But let us consider the Celestina. In that book we have two sets of principals, Celestina and her “girls” from the lower level of society and the upper class Melibea and Calisto, along with Melibea’s parents. Calisto’s and Melibea’s servants play major roles, and Melibea’s father closes the novel with a long lament. Celestina is none the less the protagonist. Her speeches would be comic were she not such a tragic figure. What chills the translator’s blood, however, is wondering how these characters spoke six centuries ago. One cannot linger in this agonizing appraisal or there will be no translation.

Each day is a challenge as one follows Celestina through countless adventures, she is rushing constantly, skirts flapping, to appointments with people who can bring her money or with her wine merchant where she buys her cheap wine. She is never still, and she believes in the power of words. One can never forget her words. So a translator squares her shoulders and digs in, preparing to do her best with a book that has entranced her but also issued a declaration that it is not going to be easy.

Yes, translation, with every problem it presents, is a wondrous pleasure.

To be continued on WorldRepublicOfLetters.org. Sign up on the WRL site for full e-mail updates before they’re posted to the site, and check out an extended, free excerpt from Celestina.

Margaret Sayers Peden is professor emerita of Spanish at the University of Missouri and the translator of major works by Octavio Paz, Pablo Neruda, Isabel Allende, and others.