Melissa Harris-Perry and Donna Hicks on the Political Power of Shame and Dignity

Melissa Harris-Perry, credit Chris Granger

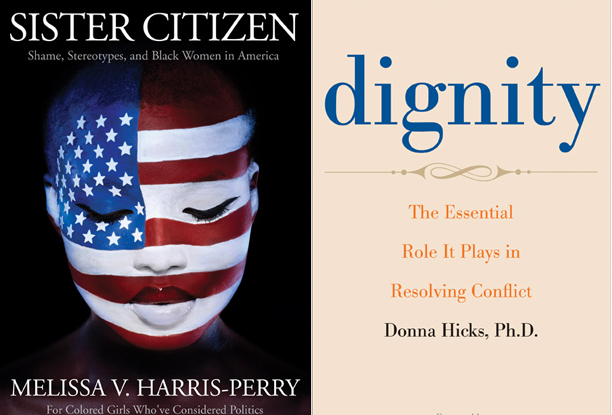

Looking ahead to September’s Political Economy theme on the Yale Press Log, this month we celebrate the one-year publication anniversary of two powerful books from Yale University Press: Melissa Harris-Perry’s Sister Citizen and Donna Hicks’s Dignity. On the surface, these authors have established themselves in very different niches of the academic and public spheres. Harris-Perry is a professor of political science at Tulane; her writing for The Nation and appearances as a commentator on national media outlets, including her own show on MSNBC, have made her a powerful public voice on the relationship of race and gender to American politics. Hicks, on the other hand, is a psychiatrist and associate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs at Harvard; she has spent most of her accomplished career as an international conflict resolution consultant, facilitating dialogues among communities in the Middle East, Sri Lanka, Colombia, Cuba, and Northern Ireland. Different as their professional paths may be, taking a closer look at their goals as researchers and citizens reveals a compelling sympathy in the work of these two remarkable women.

Donna Hicks, credit Steve Bennett

To begin with, both book projects are a testament to the idea that bridging disciplines can yield creative solutions. In Harris-Perry’s case, taking a psychological approach to the challenges faced by African-American women attempting to participate in the public arena developed out of the way women were describing this struggle to her. “At first, I expected to write a more traditional political science text about women who organize in communities and run for office,” she explained in an interview with YUP on the project, “But my research efforts kept bringing me back to black women’s internal emotional experiences. The women I interviewed were keenly aware of race and gender barriers, resource disparities, and limited opportunities, but when they talked about themselves as Americans, they focused on psychic pain, emotional stress, debilitating shame, and the pressure to live up to unrealistic expectations. Many felt that they were trying to “do politics” in an environment where no one was willing to see them accurately or compassionately.”

Hicks came to a similar realization, albeit by a different path. Over the course of her many years as an international mediator, she began to develop a theory about the central role that shame and the psychic pain of not being recognized – either by an opposing party or by their own social group – played in both individuals’ and a communities’ inability to find peace. Like Harris-Perry, her approach was born of carefully observing and listening to those who had in some way socially maligned or abused. She watched as people with years – sometimes decades – of social and political strife dividing them made legitimate steps toward change. The most miraculous of these moments, she realized, were not a product of receiving material reparations but of genuine recognition of their dignity as an inalienable human right.

Hicks came to a similar realization, albeit by a different path. Over the course of her many years as an international mediator, she began to develop a theory about the central role that shame and the psychic pain of not being recognized – either by an opposing party or by their own social group – played in both individuals’ and a communities’ inability to find peace. Like Harris-Perry, her approach was born of carefully observing and listening to those who had in some way socially maligned or abused. She watched as people with years – sometimes decades – of social and political strife dividing them made legitimate steps toward change. The most miraculous of these moments, she realized, were not a product of receiving material reparations but of genuine recognition of their dignity as an inalienable human right.

Thus, both authors end up making a compelling case for recognizing the importance of dignity to establishing (or restoring) a sense of authentic citizenship to individuals and groups. This is reflected in the confluence of the case study portions of their respective arguments. For example, despite radical differences in context, the indignities endured by the African American community after Hurricane Katrina as described by Harris-Perry resonates strongly with Hicks’s description of the indignities endured by Muslims, both in the Middle East and in the US, after 9/11. The two authors are also linked by their pragmatic approach to such a theory. Both acknowledge that “recognition” isn’t a clear cut experience. Harris-Perry quotes political scientist Patchen Markell, who writes that “Recognition [is not] a thing of which one has more or less, rather [it is] a social interaction that can go well or poorly in various ways.” Hicks echoes this sentiment with her emphasis on the importance of acknowledging what it is like in the moment to have your dignity demeaned and being realistic about the experience – what is felt emotionally, what options are available as a response, and how we can work to change those options.

Thus, both authors end up making a compelling case for recognizing the importance of dignity to establishing (or restoring) a sense of authentic citizenship to individuals and groups. This is reflected in the confluence of the case study portions of their respective arguments. For example, despite radical differences in context, the indignities endured by the African American community after Hurricane Katrina as described by Harris-Perry resonates strongly with Hicks’s description of the indignities endured by Muslims, both in the Middle East and in the US, after 9/11. The two authors are also linked by their pragmatic approach to such a theory. Both acknowledge that “recognition” isn’t a clear cut experience. Harris-Perry quotes political scientist Patchen Markell, who writes that “Recognition [is not] a thing of which one has more or less, rather [it is] a social interaction that can go well or poorly in various ways.” Hicks echoes this sentiment with her emphasis on the importance of acknowledging what it is like in the moment to have your dignity demeaned and being realistic about the experience – what is felt emotionally, what options are available as a response, and how we can work to change those options.

It might be tempting view this emphasis on recognition as a distraction from more material and policy-oriented forms of reparation for social injustice. Harris-Perry and Hicks are both keenly aware of this argument, and refute it by making a case for recognition, not as an alternative to reparation, but as a necessary component of it. After all, it is difficult to fight for, or even acknowledge, political agency without first being freed from the drive to disavow the self that shame perpetuates. As quoted in Sister Citizen, the poet Kate Rushin so eloquently writes:

The bridge I must be

Is the bridge to my own power

I must translate

My own fears

Mediate

My own weaknesses

I must be the bridge to nowhere

But my true self

And then

I will be useful

Reblogged this on Laura Pahapill.