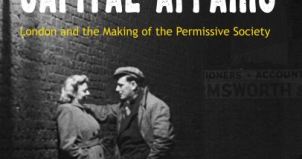

Sex, Power, and London

The researcher Alfred Kinsey came to London in 1955 “looking for sex,” according to Frank Mort’s Capital Affairs: London and the Making of the Permissive Society, and he was surprised at what he found. The amount of commercial sex on public display on the streets astounded him. Close to the fashionable shopping districts, “Soho was the backstage for exotic cultural and sexual encounters of all kinds.”

Capital Affairs is a cultural history set in London which describes a city’s shifting relationship to sex in the public sphere. Mort’s story begins with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Against the backdrop of the glittering carriage carrying the queen passing through the street were murmurings of “vice” bubbling up in the city. The coronation and the “seedy underbelly” of London’s pleasure district were not far removed from one another. Kinsey was not the only who “noted the worrying proximity of monarchy and high society to the West End’s dubious sexual playgrounds.” It is this tension between public and private, high and “low” culture that comes to the forefront in Mort’s account, where the cultural influence over sex and permissiveness travels in both directions.

Capital Affairs is a cultural history set in London which describes a city’s shifting relationship to sex in the public sphere. Mort’s story begins with the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II in 1953. Against the backdrop of the glittering carriage carrying the queen passing through the street were murmurings of “vice” bubbling up in the city. The coronation and the “seedy underbelly” of London’s pleasure district were not far removed from one another. Kinsey was not the only who “noted the worrying proximity of monarchy and high society to the West End’s dubious sexual playgrounds.” It is this tension between public and private, high and “low” culture that comes to the forefront in Mort’s account, where the cultural influence over sex and permissiveness travels in both directions.

Mort focuses on the rising public presence and legal “reform” of homosexuality and prostitution, yet these issues stand in for broader cultural shifts in London (and Britain at large). Rather than being a story of a liberal/conservative dispute, or a post-war optimistic acceptance of permissiveness, a richer and more dynamic picture emerges of the London metropolis, a place Benjamin Disraeli called “a modern Babylon” a century earlier. The author also puts the public debates in context, drawing the connection between the mores and anxieties in the ‘50s and ‘60s to Victorian narratives like those surrounding Jack the Ripper. The same themes of insatiable monstrousness, of social pathology, appear in the language around John Christie’s murders.

The Profumo scandal of 1963 is a key moment for Mort, as it stirred up competing truths about sex, power, and urban London. It began with Stephen Ward, an osteopath connected to both the aristocracy and the “underworld,” introducing the married British Secretary of State John Profumo to 19-year-old dancer Catherine Keeler. Keeler was coincidentally also having an affair with Yevgeni Ivanov, a Russian attaché involved in espionage, who was also at the party; the scandal grew increasingly complex and public. While the Profumo affair “erupted into public consciousness in the spring of 1963, its roots lay further back, in the activities of the men and women whose lives were part of elite London society during the 1950s.” The elite are then confronted by figures like the lower-class Catherine Keeler come forward, publicizing their role in the scandal with ease. In her story several threads of societal anxiety weave together: fears over the Cold War, drugs, class mobility and of course, sexual permissiveness.

In 1966, American journalist Piri Halasz wrote a cover story for Time magazine that painted of picture of London as the centre of the “swinging sixties.” The tone assumed that slow triumph of progressiveness over sexual mores where “if Britain had lost an empire, it had ‘recovered a lightness of heart lost during the weight centuries of world leadership.’” Yet in Capital Affairs we see sex as a more complex site of political power moves, class struggle, and “shot through with the divisions that marked contemporary England.”