A Different Kind of Paganism

Anthony Kronman—

For more than a dozen years, I’ve been teaching in Directed Studies—a traditional, Great Books program for freshmen in Yale College. Programs of this kind are increasingly rare on America’s campuses. But I believe deeply in the spirit of liberal learning that they represent and in 2008 published a book entitled Education’s End, in which I sought to describe and defend the educational principles that underlie Yale’s Directed Studies Program and others like it.

Shortly after the book was published, I was speaking about it to a public audience here in New Haven. During the question and answer session, a thoughtful gentleman at the back of the room asked if we read any “religious” texts in Directed Studies, and if so, what I thought about them. I said that yes, of course, we read religious works along with secular ones, including large selections from the Bible as well as books by Augustine, Dante, Kierkegaard and others. I emphasized, though, that I did not think it appropriate for me as a teacher to take a position in class “for or against God,” but only to expose my students to a range of views and to help them form a thoughtful position of their own. My questioner replied that he respected my pedagogical intentions but was really most interested in knowing where I stood on the issue. “What issue?” I asked. “Why, whether or not you yourself believe in God,” he responded. I told him that I would have to get back to him on that and quickly called on someone else.

But the question haunted me. I have never been a religious person in the sense in which that phrase is most often used. I don’t believe in a God beyond the world, sitting in judgment on our doings down below, and parceling out rewards and punishments according to our deserts. But at the same time, I have never been comfortable with my skeptical, atheist friends who declare—sometimes, I think, with an energy that perhaps betrays their own anxieties—that it is only a child or a fool who believes in anything “divine” or “everlasting” (to use the terms that Aristotle employs whenever he is speaking about God). Put more positively, I’ve always regarded myself as a spiritual person for whom the numinous aura that surrounds all things is even more impressive than the things themselves. But what does it mean to spiritual yet not religious? That was a question that had lain dormant in my mind (and soul) until I was asked, in a public and perfectly reasonable way, to declare myself for or against God—or, as I have come to think of it since, to describe and defend the kind of God that animates my own non-religious spirituality.

So for the past eight years I have devoted myself to answering this question. I started by asking what exactly I find unacceptable about the God of the Abrahamic religions. (I’m a Jew, but for purposes of this question, I could as easily be a Christian or Muslim.) The God of Abraham demands an obedience that cannot be rationally justified. And he (forgive the gendered pronoun) is an all-powerful creator who is by definition separate from the world. I have a boundless commitment to reason and demand a God compatible with it. I also need a God who is closer to the world than the God of Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed can possibly be. So turning away from the God of Abraham, I went back to the God of my beloved Greek philosophers, and to that of Aristotle in particular, for whom one might say that God is nothing but the inherent intelligibility of the world itself. I found this conception of God more appealing. But Aristotle’s theology suffers from a fundamental shortcoming. It is incapable of explaining how the uniqueness of any individual, human or other—the particular set of qualities that distinguishes every individual from all the others in the world—can itself be invested with divinity, as all the Abrahamic religions assume. Put differently, Aristotle’s God is defective because, though immanent in the world rather than separate from it, and coincidental with reason instead of conflicting with it, it nevertheless lacks the infinitude (of power, being, and reality) that is the most distinctive feature of the God of all the Abrahamic religions.

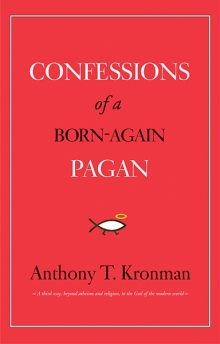

At this point, I realized that I wanted to have my cake and eat it too. I wanted a God of infinite reality (like the God of Abraham) whose being is identical with that of the world and reason itself (like the God of Aristotle). But where is such a God to be found? As it turns out, once I began looking in earnest, I discovered the God for whom (for which?) I was searching in many places, including Spinoza’s Ethics—the book that has become my guide in wrestling with these thorny theological issues. To describe Spinoza’s theology, which combines certain features of Aristotle’s pagan conception of God with others that belong to the infinitely powerful God of the Abrahamic religions, I invented the phrase “born-again pagan.” After I had begun to think of Spinoza in these terms, I discovered many other thinkers, in the worlds of science, art, and politics, who can be described as born-again pagans too. I slowly came to see that their God anchors a form of spirituality that no longer depends on religion in the conventional sense, and that their God is mine. I now believe it is the God of many others as well. And that thought has not only given me solace. It has at last equipped me to answer the question that I found myself so ill-prepared to address some years ago when I was asked whether, having read the books in Directed Studies and wrestled with my students about the issues they raise, I could confidently say there is a God and, if so, what I might mean.

Anthony T. Kronman served as dean of the Yale Law School from 1994 to 2004. He currently divides his time between the Law School and the Directed Studies Program in Yale College. He lives in New Haven, CT.

Further Reading

Dear Professor Kronman,

You sound like an honest and earnest man; you are asking the big questions and trying to come up with some answers, tentative as those may be. Allow me to make a suggestion. Dip into the writings of Camille Paglia. Dare to encourage your students to read her books, along with your own. Broaden your horizons and be enriched!

I wish you long life, good fortune, and stimulating class discussions!