The Artful Religion of William Blake

Leo Damrosch—

Religion was profoundly important to Blake, in a questing and questioning way that is thought-provoking even for readers and viewers who are not religious at all. One of his first experiments in relief etching was a little pamphlet entitled All Religions Are One, which asserts that however much religions may differ in detail, they have a common origin. “The religions of all nations are derived from each nation’s different reception of the poetic genius, which is everywhere called the spirit of prophecy. . . . As all men are alike (though infinitely various) so all religions; and as all similars, have one source. The true Man is the source, he being the poetic genius.”

That sounds definite, but what, really, is “the true Man”? Answering that question was a lifelong challenge for Blake. He always denied the existence of an omnipotent patriarch in heaven, and he would sometimes insist that the divine was simply a spiritual dimension that all human beings share. Thus, in The Marriage of Heaven and Hell: “All deities reside in the human breast.” And the notebook verses known as The Everlasting Gospel include this unequivocal statement:

Thou art a man God is no more

Thy own humanity learn to adore.

But as Blake labored long and hard on The Four Zoas, and afterward on the prophecies Milton and Jerusalem, the figure of Jesus took on an increasingly crucial role. Concerned as he was with the breakdown of the self, he needed help from an agency beyond the self; without intervention by “the Saviour even Jesus,” the fall into formlessness would have no end. If Jesus were simply what is best in humanity, what would be the point in calling him “the Saviour” at all?

The function of religion, in Blake’s view, is to ask ultimate questions about existence, and the questions are more important than the answers. He did declare once, “The Old and New Testaments are the great code of art,” but that doesn’t mean that the Bible has a monopoly on truth. Rather, the Bible is the particular set of symbols that are embedded in the Western imagination, inspiring Blake as it inspired Michelangelo and Raphael before him. But he always read the Bible, as Erdman puts it, counterclockwise, in explicit contrast to orthodox interpretation. As Blake says in The Everlasting Gospel,

Both read the Bible day and night

But thou read’st black where I read white.

Blake explicitly rejected a great deal in the New Testament, including the doctrine of the virgin birth and the Pauline emphasis on sin. He liked the Old Testament even less, apart from the visionary prophets. The stony tablets of the Ten Commandments are a negative symbol throughout his work, as is the institution of priesthood with its repressive Law: “As the caterpillar chooses the fairest leaves to lay her eggs on, so the priest lays his curse on the fairest joys.” Blake was especially revolted by biblical military history. Reading an Anglican bishop’s claim that it must have been God’s will “to exterminate so wicked a people” as the Canaanites, he retorted, “To me who believe the Bible and profess myself a Christian, a defence of the wickedness of the Israelites in murdering so many thousands under pretence of a command from God is altogether abominable and blasphemous.”

∞

After the Songs of Innocence, Jesus all but disappeared from Blake’s poems for nearly a decade, reappearing at last during revision of The Four Zoas. He probably disappeared because Blake saw him as coopted by organized religion, and he probably returned when Blake realized he needed a power greater than ourselves, able to rescue us from our troubled condition. That was when he wrote to Butts, “I am again emerged into the light of day. I still and shall to eternity embrace Christianity, and adore him who is the express image of God.”

It seems clear that Blake regarded the historical Jesus as a great prophet but not as the unique incarnation of God on earth. Jesus was perhaps endowed with exceptional divine inspiration, but if so he differed from the rest of us in degree, not kind. A rather shocked Crabb Robinson reported: “On my asking in what light he viewed the great question concerning the divinity of Jesus Christ, he said, ‘He is the only God;’ but then he added, ‘And so am I and so are you.’” Strikingly, Robinson adds, “Now he had just before (and that occasioned my question) been speaking of the errors of Jesus Christ.”

According to orthodox theology, God could not forgive our sins until the innocent Christ permitted himself to be executed on our behalf. “That is a horrible doctrine,” Blake told Robinson; “if another man pay your debt I do not forgive it.” To glorify the Crucifixion, therefore, struck Blake as altogether blasphemous, since he saw it not as a divine sacrifice but as a judicial murder of the historical Jesus. In the “Keys of the Gates” appended to For the Sexes he challenges believers to justify their use of the crucifix:

O Christians Christians! tell me why

You rear it on your altars high!

A full-page image of the Crucifixion appears in Jerusalem, symbolizing temporary bondage to the natural world. Jesus hangs not from a cross but from a tree that resembles a massive oak, recalling the nature worship of the despised Druids. Yet there are apples hanging from it. Evidently this is no botanically recognizable tree, but a conflation of all the mythic forms of human sacrifice. In Blake’s terms, what Jesus has really done is sacrifice his own selfhood, not in order to propitiate a vengeful God but to purge away the merely “natural” in all of us. Albion (whose name is visible in several copies of this plate) stands adoring Jesus, from whose head pours a radiance far brighter than that of the merely natural sun on the horizon. Albion’s outstretched arms mirror the cruciform pose, and his posture recalls the “dance of death” in the print Albion Rose. Jesus is the only God—but so is Albion, and so are we all.

∞

From Songs of Experience onward, it is obvious that Blake had a problem with fathers, though it is never clear why. All the same, his symbolism would be crippled if it dismissed fatherhood altogether. Just as Urizen must be reintegrated with the other Zoas, so Jehovah must recover a positive role. “I see the face of my Heavenly Father,” Blake wrote to Butts near the end of the time at Felpham; “he lays his hand upon my head and gives a blessing to all my works.” In Jerusalem we hear of “the universal Father.”

The next to last plate of Jerusalem is a scene of reconciliation, but strange and hard to interpret. A bearded old man, with rays of light springing from his head, leans forward to embrace an androgynous figure with long hair who may be Jerusalem or possibly humanity as a whole. The colors are so dark that an art historian complains, “The black-red Blakean oven is peculiarly grim and smothering.” Morton Paley, on the other hand, says that “the variation of darks in the flames creates a truly apocalyptic effect” and notes the striking use of blue sky as a halo.

Is the bearded figure a return, at last, of the Father? The younger figure seems to be falling gratefully into his arms, gazing up into his face. But why is the old man gazing off to the side? Is he looking at us? And why does he grasp the young figure’s buttocks? Commentators have understandably seen the embrace as sexual, but is it? One interpreter sees the younger figure as “a terror-stricken androgyne”; another sees no terror but rather “the rapturous moment just before erotic consummation; Jerusalem and Albion are rising within the earth in heavenly flames, and ‘the time of love’ with its orgasmic ‘holy raptures of adoration’ is spreading forgiveness and life within and throughout the earth.” As so often, it’s hard to know if intense sexual feelings are actually implied in the picture or are just imagined by Blake’s commentators.

A different interpretation is suggested by Anthony Blunt, who notes the similarity of the embrace in this image to that of the Prodigal Son and his father in an engraving by Martin de Vos. We know that Blake found that parable especially moving. Samuel Palmer told Gilchrist, “I can yet recall it when, on one occasion, dwelling upon the exquisite beauty of the parable of the Prodigal, he began to repeat a part of it; but at the words, ‘When he was yet a great way off, his father saw him,’ could go no further. His voice faltered, and he was in tears.” Here is what Blake was unable to finish:

But when he was yet a great way off, his father saw him, and had compassion, and ran, and fell on his neck, and kissed him. And the son said unto him, Father, I have sinned against heaven, and in thy sight, and am no more worthy to be called thy son. But the father said to his servants, Bring forth the best robe, and put it on him; and put a ring on his hand, and shoes on his feet: and bring hither the fatted calf, and kill it; and let us eat, and be merry: for this my son was dead, and is alive again; he was lost, and is found.

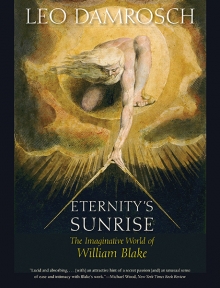

From Eternity’s Sunrise by Leo Damrosch, published by Yale University Press in 2005. Reproduced by permission.

Leo Damrosch is Research Professor of Literature, Harvard University. His previous books include Jonathan Swift: His Life and His World, winner of the National Book Critics Circle Award in biography and a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in biography. He lives in Newton, MA.