Of Peaches, Pears, and Politics

Patricia Mainardi–

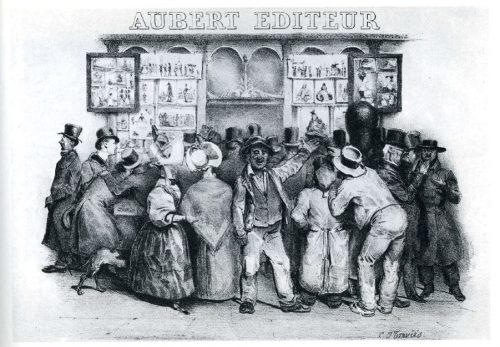

Traviès’s 1831 lithograph shows a man gesturing towards a display of caricatures while saying “You have to admit that the head of state looks pretty funny”. It could serve as a banner for all political cartooning, an art that is at its best in difficult times. Simply put, in good times we don’t need the talents of artists whose skill, as Art Spiegelman so aptly pointed out, is “Drawing Blood.” Comic strips and graphic novels might also have political themes (witness Gary Trudeau’s Doonesbury), but they communicate them through narrative sequences recounted in multiple frames. The political cartoon, on the other hand, must imbricate within a single image its entire meaning; at its best it is a tour de force of concision, functioning more like poetry than like prose. On one level it is simple reportage, but at the same time it operates on a metaphoric level, beckoning us into a world of allusion and symbolism that extends and expands its significance.

Édouard Traviès, “You have to admit that the head of state looks pretty funny,”

Published in La Caricature, December 22, 1831

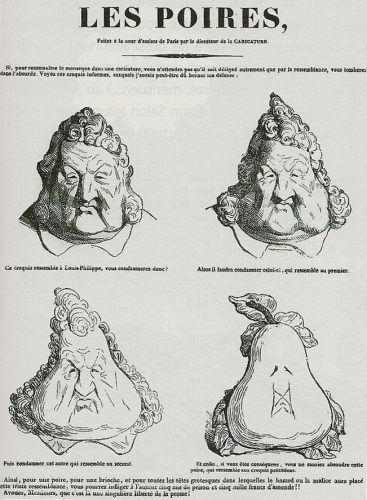

Cartoonists look for an easily recognizable feature that can serve as a kind of shorthand notation to conjure up a spectrum of meanings. We can trace this strategy back to the illustrious prototype of political caricature, Charles Philipon’s depiction of the French king Louis-Philippe. In 1831 Philipon was arrested for publishing an all-too recognizable satiric drawing of the king; at his trial he defended himself by claiming that one could see anything in an image and he demonstrated this by drawing Louis-Philippe transformed into a pear. The unfortunate resemblance of Louis-Philippe’s pear-shaped visage to that fruit certainly provided Philipon with his initial inspiration, but at the same time it could function on a symbolic level because the French word for pear, poire, signifies a fool, a dullard. The court was not amused, however, and as reward for his wit Philipon spent some time in jail. Nonetheless, after Honoré Daumier redrew Philipon’s pears for publication, cartoonists adopted it as their preferred symbol for the despised king and the pear became a symbol of resistance, scribbled on walls everywhere.

Honoré Daumier, Pears, after the drawing by Charles Philipon; Published in La Caricature, November 24, 1831

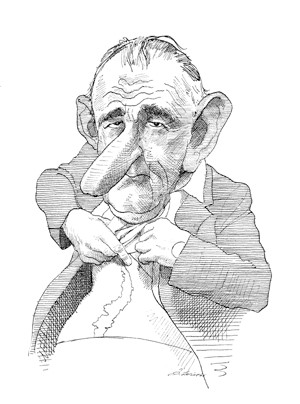

Ridicule has always proved to be a potent weapon: Thomas Nast’s depiction of Boss Tweed with his outsized belly, Oliphant’s drawings of a swarthy “Tricky Dick” Nixon emerging from a murky background. When Lyndon Johnson, always associated with the unsuccessful war he waged, flashed his gall-bladder scar for reporters, David Levine seized on the event by drawing Johnson lifting his shirt to reveal his scar … in the shape of Vietnam. Subsequent presidents–Bush, Clinton, Obama–were targets of caricature as well, but the results never equaled the barbs directed at Nixon and Johnson.

David Levine, Untitled caricature of Lyndon B. Johnson; Published in The New York Review of Books, May 12, 1966

BT (before Trump), one might have thought that political caricature in America was a declining art because fewer and fewer periodicals publish it regularly. But now, judging from the numerous images posted daily on websites like EditorialCartoonists.com and Facebook’s Editorial & Political Cartoons, the genre seems to be entering a new Golden Age. Cartoonists have quickly adopted Trump’s yellow hair as his defining physical characteristic, just as Louis-Philippe’s pear-shaped visage, Johnson’s ski-jump nose, and Obama’s elephant ears immediately identified those figures. Cartoonists often say that the best cartoons have minimal or no text, so that the image itself can carry the meaning. By this standard, Dana Bowers, an artist with the Indivisible group “Democracy Spring Georgia,” has created a superlative image, for amidst the immense surge of creative energy directed toward politics, she has created a new meme, a fitting tribute to the fruit tradition of political humor that originated with Philipon’s pear. For “imPEACH”, Bowers adapted the Georgia state symbol to create a symbol that is now so familiar at marches, rallies and protests that, like Louis-Philippe’s pear, it needs no caption.

Dana Bowers, imPEACH, 2017

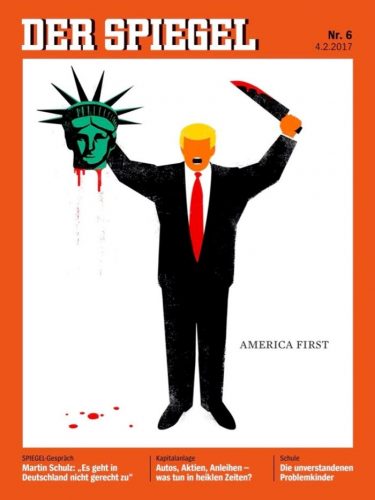

The most widely-reproduced cartoon to emerge from our current political scene is “America First” by the Cuban-born American immigrant Edel Rodriguez. Published as the cover of the German weekly Der Spiegel, his cartoon has become known throughout the world, perhaps a fitting revenge for this American artist who is both an immigrant and of Latino origin, two of Trump’s avowed targets. “America First” banks on the simple recognition of three well-known tropes: the head of Bartholdi’s statue of Liberty, the pose of Canova’s sculpture Perseus Holding the Head of Medusa, and Trump’s improbable yellow hair. The ambiguous title refers to Trump’s campaign slogan, to be sure, but read in conjunction with the image it also implies that liberty will be destroyed first in America and then, later, elsewhere.

Edel Rodriguez, “America First”, Der Spiegel, February 4, 2017

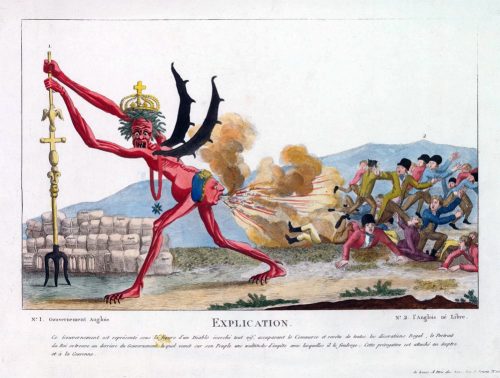

Rodriguez’s image easily takes its place in the pantheon of political cartoons, comparable in its severity to Jacques-Louis David’s English Government two centuries earlier, where King George III’s head is depicted breathing fire through the devil’s backside.

Jacques-Louis David, English Government, 1793

As the United States experiences an unprecedented level of attack on freedom of the press, the response from the world of art has been – as has happened many times in similar situations in other countries – that artists are focusing their energies on the creation of images that distill at a glance the essence of their – and our – resistance. As Edel Rodriguez writes: “The purpose of political art is not necessarily to change minds, but to mark a moment in time. So that future generations can see that people were not silent when the world changed around them.”

Patricia Mainardi is professor emerita of art history at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and Chevalier in France’s Order of Academic Palms. She has received the College Art Association’s Charles Rufus Morey Award and numerous fellowships, including from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Institute for Advanced Study. She is the author, most recently, of the book Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture. Professor Mainardi will talk about popular prints and comics at the New York Comics & Picture-Story Symposium on April 25th.