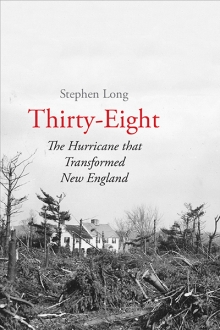

The Lingering Damage of a Deadly Hurricane

Stephen Long—

It can seem like a long wait for Spring to replace the browns and grays of the woods with tints of green. But this time of year has its benefits. Before lush growth turns the woods into a maze of green, we have a chance at an unobstructed look into the structure of the woods. Because of my huge interest in forest history, I see this as a prime time to peer into unfamiliar woods to see whether or not they were blown down in the 1938 hurricane. Without leaves on the trees, you can get a great look at tree trunks and the ground level topography, which provide clues to the past.

The hurricane of September 21, 1938, blew down 600,000 acres of New England forests in a single afternoon. Destruction varied tremendously, with some large swaths blown over and others merely inconvenienced by losing their leaves on the cusp of Autumn. Given that variability, I start my explorations by looking for places that would have been in the crosshairs of the 100 mile-per-hour winds that came from the southeast. Flat or gently rolling terrain would have been vulnerable, though not as much as hills that faced either to the south or east. The backsides of those hills—facing north or west—would likely have escaped the worst of the damage.

The most telling sign of hurricane damage is the hummocky terrain known as pit-and-mound topography. The ground in hurricane woods is pockmarked with deep depressions adjacent to correspondingly large mounds. This undulating ground tells you that trees have blown down here, and the tip-ups (uprooted trees) have transformed the forest floor. The root system of a forest tree forms a plate, and when wind knocks the tree over, the roots are wrenched out of the ground with only a hinge of roots maintaining its attachment to the ground. As the rest of the roots rip free, they grasp a mass of soil and stone, excavating a hole. The bigger the tree, the bigger the pit.

Over time, the roots and stump decompose, leaving a mound of earth. Nearly eighty years after the event, it looks as if somebody dug a hole and piled the dirt next to it. This happens anytime the wind uproots a tree, not just during a hurricane. But there’s a way to tell whether it was hurricane damage. Stand in the pit, look out across the mound, and that’s the direction that the tree fell. The felling wind was at your back. If you’re facing north or northwest, the hurricane probably did the deed because the hurricane’s strongest winds were from the southeast.

A southeast wind strong enough to uproot trees is a rarity in interior New England, where the everyday prevailing wind tends to come from the west, so most everyday gusts—including those from microbursts embedded in thunderstorms—blow trees down to the east. The layout of the pits and mounds will confirm the wind came from the west. So, if you come across a section of woods with all of pits and mounds pointing to the west or northwest, it’s a sure sign that Thirty-Eight did the deed.

With that thought in mind, look at the tree trunks. If you see scattered hardwoods with a boomerang shape or hemlocks with a gentle curve, they may have been tipped by the wind but not uprooted. Phototropism—the ability in trees to sense sunlight and grow toward it—corrects the trunk’s lateral lean and sends it sunward in either of two ways. Softwoods can simply recurve themselves back toward vertical. It’s different with hardwoods, which tend to sprout in response to injury. A side branch pointing toward the sun will take over as the main trunk. Over time, the rest of the tree beyond the new leader sloughs off, giving it the boomerang shape. Again, direction is the key. If the tipped portion of the tree is pointing north or northwest, credit Thirty-Eight. You may be surprised at the lack of size of some of these, especially if they are shade-tolerant species: maple, beech, and hemlock. These can spend decades in the shade without putting on much girth because they are very adept at photosynthesizing filtered light. Other species that languish for decades are more likely to give up the ghost.

You may come across the occasional behemoth in the woods. Its size tells you it’s old, and its form can tell you about its history. If the trunk features knobby protrusions in the first 10 feet of height, that shows that this tree grew out in the open with its lower limbs reaching for light. Later, when younger trees grew up surrounding it, the limbs fell off while the upper branches competed for the light. The knobs are remnant stubs of self-pruned branches. Chances are you won’t see much pit-and-mound around trees like this because they were the only ones there. When the hurricane came through, there weren’t any nearby oaks or pines or maples. Instead, the ground was covered with clover, timothy, and brome.

These trees survived in the face of Thirty-Eight’s 100 mile-per-hour winds, because standing in the open, they experienced years of wind that strengthened their roots’ purchase. They stayed anchored, though their crowns probably shed some branches, maybe even some major limbs.

Stephen Long is founder and former editor of Northern Woodlands magazine and author of More Than a Woodlot: Getting the Most from Your Family Forest. For more than twenty-five years he has been writing about the forests and people of New England while exploring his own woods in Corinth, VT.

Further reading: