Torosaurus, Sea Form: What’s in a Name?

James Prosek—

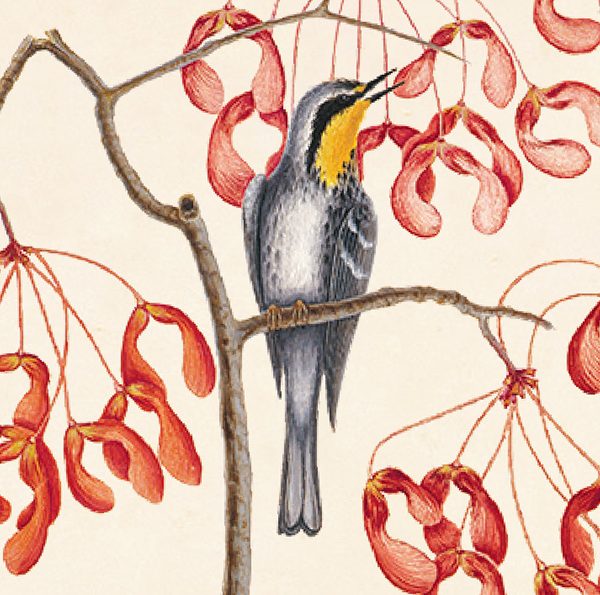

For an exhibition at the Yale University Art Gallery and an accompanying book, both titled James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice, I juxtaposed objects from the collections of the Gallery, the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History, and the Yale Center for British Art and works made by me. (See details at the end of this post for an online launch event!) A central theme of the exhibition and book is how and why we name and order nature, a topic I’ve long been obsessed with. My fascination with names began when, as a child immersed in and passionate about the natural world, I noticed that the imposition of words on the world was beautiful and necessary, but also problematic.

As it happens, O. C. Marsh, the founder of the Peabody Museum, was a famous taxonomist—a person who names things for a living. He was a pioneer of putting names on newly discovered fossils of ancient lizards. Marsh, sometimes called the father of American paleontology, discovered and named many of the most well-known dinosaur species that we learn as children—Brontosaurus, Stegosaurus, Triceratops.

Early in the process of selecting objects for the exhibition, I began to fantasize about including a dinosaur skull. The one that was most visually appealing and remarkable to me, not just for its size but also for its shape and form, was Torosaurus latus. Torosaurus was discovered in Wyoming in the summer of 1891 by one of Marsh’s hired hands, the fossil hunter John Bell Hatcher, and was named by Marsh. At nine feet long from its nose to the back of its head, it is the largest skull of any animal to have ever walked the earth.

In discussions with the Gallery’s chief curator, Laurence Kanter, I proposed bringing Torosaurus across campus, from the Peabody to the Gallery. But would we even be able to get it into the building? We learned that it was too big to fit in the elevator, and therefore we couldn’t install it in the exhibition galleries, but we could get it into the lobby. After some lobbying for the lobby, we were able to start planning to bring the skull to the Gallery. It had not been moved since the 1920s.

Next question: What to install next to it? Even by itself beneath the iconic tetrahedral ceiling of the Gallery’s Louis Kahn–designed building, the skull would create beautiful visual vibrations (the Torosaurus skull is essentially a triangular pyramid). Built in the 1950s, Kahn’s space feels primordial; it gives me the impression that it was mined or excavated from the ground—ancient, timeless, sensitive to light. The Kahn building’s surfaces bear the mark of other materials used in the construction process. On the concrete surfaces, for instance, you can see the imprint of the milled wood used as forms into which the concrete was poured. Some fossils are made in a similar way—a dinosaur walked in mud and left an impression. The tracks got covered by layers of sediment, and over time the residue of these animals’ movements millions of years ago became mineralized. Footprints and bones, things that would ordinarily have been swept away by rain and wind or succumbed to decay, were documented—the record of their existence made more permanent—by a set of unusual circumstances that led to their preservation in stone.

I realized that the perfect artwork to install next to the Torosaurus was the Gallery’s sculpture Sea Form (Porthmeor), by the English modernist artist Barbara Hepworth. Both objects have three prominent holes or cavities—the dinosaur skull has two holes in the frill in the back of its head and one on the top of its beak-like snout, while the Hepworth work, with its three holes, almost looks like a melted version of the skull.

To me, the sculpture resembles a curling or cresting wave just at the moment before it makes contact with the shore. The jade patina Hepworth chose, and the shape, make the sculpture look more like sea foam than sea form: a manifestation of movement in metal. And in some sense, with the Torosaurus skull, nature did the same: it produced a three-dimensional rendering of a living, breathing organism and froze a part of its body in the process of entropy and decay after death, in a permanent material—stone!

Beyond the visual, this juxtaposition is also, as I said, meant to provoke thoughts or discussions about what it means to name things. I like the idea that both the discoverer of the dinosaur, Marsh, and the maker of the sculpture, Hepworth, had given names to the objects, names that helped them “become” things—to enter the reality of humans.

Some artists choose to give their works titles. Many artists, especially abstract artists of the 20th century, began to label their works with numbers, or to simply call them “untitled.” Both a number and “untitled,” one could argue, are still titles, but in attempting an anti-title the artist is making a subversive statement, offering an alternative to labeling. Labels can indeed be helpful for purposes of communication, but they can also distract a viewer from formulating their own opinions about an artwork. Labels can perniciously lock an object or organism into a single perspective. The act of naming carries a legacy of domination and control, and conquest (especially since much of the enterprise of naming species in a universal and formal way began during the colonial period). Certainly for Marsh, naming a new dinosaur announced a previously unknown segment of the evolutionary continuum, but it also gave him an opportunity to promote his legacy by being the first to name it. By leaving an object “untitled,” an artist is expressing that there are non-lingual ways of communicating experience and emotion.

In a sense, what art tries to capture is the unnameable, the ephemeral, the elements of personal experience that science cannot quantify or solve. Science, to a certain extent, tries to understand the whole by dividing it into discrete parts (often labeling them), and hoping that when the pieces are put back together again they will explain the whole. Art inherently acknowledges that the whole is something different than the assembled pieces and, instead of trying to explain it, attempts to preserve and cherish the ineffability of existence without division.

By placing two objects alongside each other that ordinarily would not be juxtaposed, a sculpture and a dinosaur skull (art and artifact), I am encouraging a new ecosystem of thought that will allow us to suspend, at least momentarily, the traditional boundaries we as individuals might place between these objects (a version of rearranging the furniture, so to speak). In suspending our expectations and prejudices, we expand the possibilities of the ways in which we see and understand objects—as well as the rest of the world around us.

Artist, writer, and naturalist James Prosek was the 2018 Happy and Bob Doran Artist in Residence at the Yale University Art Gallery.

The Yale University Art Gallery’s first virtual book launch!

James Prosek will read from the introduction to the book, in which he discusses the origins of his deep connection with nature and his lifelong investigation into the boundaries that humans draw on the world around them. The reading will be followed by an audience Q&A moderated by Tiffany Sprague, Director of Publications and Editorial Services. Generously sponsored by the Milton and Sally Avery Arts Foundation and Donna and Marvin Schwartz. Presented in conjunction with the exhibition James Prosek: Art, Artifact, Artifice.

Registration required; to register, click here. The first three people to register for and attend this program will receive a free signed copy of the catalogue.

While the Gallery is closed, you can still purchase the catalogue at yalebooks.com or from your favorite online bookseller.

To learn more about the exhibition, visit the Gallery’s website or download its free audio guide.